Guest Essayist: David B. Kopel

In 1949, after more than 20 years of fighting, the Chinese Communist Party overthrew the Republic of China. The party’s chairman, Mao Zedong, became dictator, and ruled until his death in 1976. Mao’s regime was the most murderous in history. His regime killed over 86 million people—more than Hitler and Stalin combined.

In 1966 Mao initiated “The Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution.” It started as a campaign against the more pragmatic elements of the Chinese Communist Party—such as leaders who a few years before had forced Mao to retreat from an agricultural collectivization program, the Great Leap Forward, that had caused the deadliest famine ever.

Incited by Mao, the Cultural Revolution began with the most privileged students—the children of the top communist party officials—at the top universities. They rioted, rampaged, and looted, first on-campus and then beyond. They started by killing or torturing teachers, and then moved on to the general public. Soon, the rage mobs of ultra-Maoists spread nationwide. Anyone’s home could be invaded and looted, and anyone could be murdered or tortured. The police were forbidden to interfere—or even to fight back when the mobs assaulted the police.

As the Cultural Revolution continued, things got even worse. The Cultural Revolution ended only when Mao died.

The Americans who created the United States Constitution could not know about the tyrants who would arise in the twentieth century. They did know of bad men who had tried to seize absolute power, such as Julius Caesar in the Roman Republic, or King James II of England. Yet the worst of English kings or Roman emperors were mild in comparison to the totalitarian Mao regime.

The American “people did not establish primarily a utility-maximizing constitution, but rather a tyranny-minimizing one.” Rebecca I. Brown, Accountability, Liberty, and the Constitution, 98 Columbia Law Review 531, 570 (1998). This essay describes some of the provisions of the U.S. Constitution that aim to thwart absolutism and totalitarianism. The information about China under Mao is based on David B. Kopel, The Party Commands the Gun: Mao Zedong’s Arms Policies and Mass Killings, Chapter 19.D.3 in Nicholas J. Johnson, David B. Kopel, George A. Mocsary, E. Gregory Wallace & Donald E. Kilmer, Firearms Law and the Second Amendment: Regulation, Rights and Policy (Aspen Publishers, 3d ed. 2022), pp. 1863-1966. Additional citations are available therein.

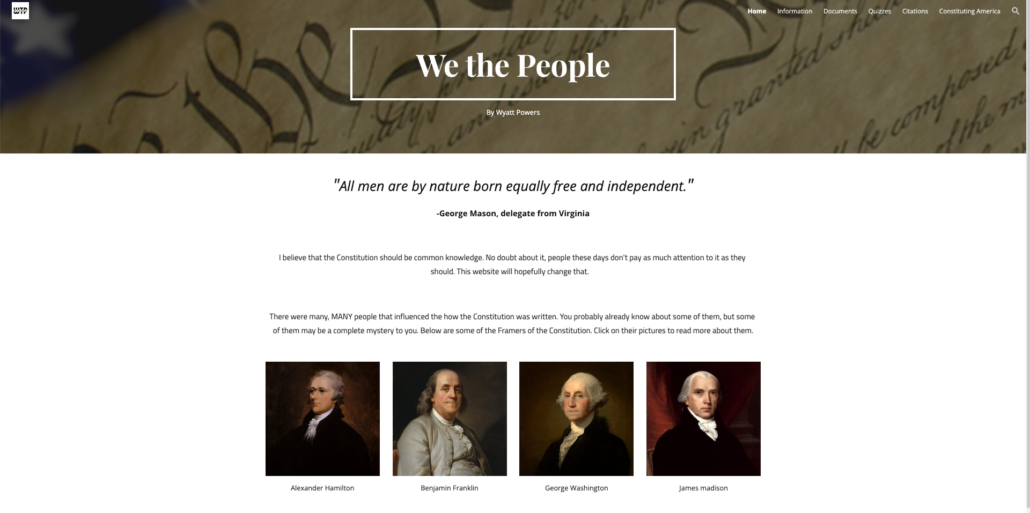

The Preamble to the Constitution states:

“We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

The principles and the results of the Mao regime were the opposite. For example, starting in 1972-73, the people were ordered to condemn the “reactionary” ideas of Confucius, such as “the people are the foundation of the state,” and “depositing riches in the people.” As described below, the Mao regime cultivated injustice, domestic violence, the welfare of the ruling class at the expense of the people, and the eradication of liberty. The regime did “provide for the common defense” in the sense that China was not invaded in 1949-76, other than in some border clashes with the Soviet Union.

The U.S. Constitution creates three distinct and independent branches of government:

“All legislative powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States.” Art. I, §1.

“The executive power shall be vested in a President of the United States of America.” Art. II, §1.

“The judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish.” Art. III, §1

Under the U.S. Constitution, the three branches of government check and balance each other, as power is set against power. In a communist regime, there are no checks on the party’s will. All political power belongs to the party. Under Mao, “at the top, thirty to forty men made all the major decisions. Their power was personal, fluid, and dependent on their relations with Mao.” Andrew J. Nathan, Foreword, in Li Zhusui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao xi (Tai Hung-Chao trans. 1994).

“The House of Representatives shall be composed of members chosen every second year by the people of the several states.” Senators are to be elected every “six years” and the President every “four years.” Art. I §§2-3; Art. II §1.

There have been no elections since the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) seized power in 1949. Although the party calls the nation it rules the “People’s Republic of China,” the name is a lie. In a “republic” where “the people” rule, the people elect government officials. In the People’s Republic of China, the party rules because the military keeps the party in power. It is reasonable to infer that the CCP knows that if free elections were held, the CCP would lose.

Particular types of “power” are granted to each of the three branches of government. Arts. I §8, II §§2-3, III §2.

The three branches of United States government are granted certain powers by the people. The branches of government may exercise the particular powers expressly granted by the Constitution, as well as some incidental powers that are implied by the express grants. No branch of government, and not even the U.S. government as a whole, has all possible powers.

A communist regime claims unlimited power over everything. Mao acknowledged no legal limit on himself. The practical limit was the difficulty of one man imposing his absolute will on hundreds of millions. The Cultural Revolution was Mao’s method for eliminating everything and everyone that impeded his power.

Congress creates law by passing a “bill,” in compliance with certain procedures. Art. I §7.

The Mao regime was not based on law. As Mao told the very sympathetic American journalist Edgar Snow, “We don’t really know what is meant by law, because we have never paid any attention to it!” Li Cheng-Chung, The Question of Human Rights on China Mainland 12 (1979) (statement to Edgar Snow 1961).

During the 1950s, there were some efforts to create normal legal codes, but these were abandoned once the Great Leap Forward into full communism began in 1958. In contrast to the Hitler regime, which issued many statutes and regulations, the Mao system relied mainly on edicts from the communist leadership, the Party Center. There were many exhortative propaganda campaigns based on slogans.

The party-controlled national newspaper, the People’s Daily, was read to peasants and workers in frequent, mandatory political instruction meetings, which often consumed the rest of the day after work. In effect, the latest article in the People’s Daily was the official source for people to learn how to behave without getting in trouble with the authorities. As different factions within the CCP gained ascendency, the edicts changed frequently. So doing what had been mandatory on Monday could be punished on Friday.

“The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in cases of rebellion or invasion the public safety may require it.” Art. I §9.

When a court issues a writ of habeas corpus, whoever is holding an individual prisoner must appear in court and prove to the court that the detention of the prisoner is lawful. In communist regimes, there is no recourse for individuals who are arbitrarily imprisoned or sent to slave labor camps.

Neither the federal government nor the states may enact any “ex post facto law.” Art. I §§9-10.

In other words, a criminal law cannot retrospectively punish an act that was lawful at the time it was committed. Just the opposite under Mao and all communist regimes. For example, in the 1956 Hundred Flowers period, people were encouraged to frankly express their views about perceived shortcomings of the CCP. Later, persons who had done so were imprisoned or sent to slave labor camps.

Likewise, during the first several months of the Cultural Revolution, young people from all over China were given free train tickets to see Chairman Mao speak at mass rallies at Tiananmen Square in Beijing. This was an exception to the normal rule that a person could not travel away from his or her village.

A few years later, when factional politics within the CCP had changed, 3.5 million people who had attended one of the 1966 rallies were given other free tickets: one-way transportation to forced labor in the countryside.

Throughout the Mao era, people were often punished for acts that had been lawful at the time, such as expressing non-communist political opinions in the 1930s.

“The President shall, at stated times, receive for his services a compensation, which shall neither be increased nor diminished during the period for which he shall have been elected; and he shall not receive within that period any other emolument from the United States, or any of them.” Art. II §1.

The President’s salary and expense accounts are set by Congress. Mao, in contrast, treated himself to whatever he wanted. In Beijing he lived in the former palace of the emperors, with his own private swimming pool and beach. He had fifty more fortified palaces around the country.

The special Giant Mountain (Jushan) farm supplied fine foods daily to the portly Mao and the others at apex of the CCP food chain. When Mao was away from Beijing, which was most of the time, daily airplanes delivered food from Jushan. The élite CCP leadership in the provinces had similar arrangements for special food, while the masses starved.

Mao enjoyed the company of many beautiful young concubines, procured for him by government employees.

During the Cultural Revolution, everyone had to buy a book of his sayings, Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong, popularly known as “The Little Red Book.” Mao decided that he was entitled to royalties from all the forced book sales, and he became the first millionaire in Communist China.

As explained by a former vice-president of communist Yugoslavia, all communist governments eventually replace the old wealthy class with a new class of reactionary despots. Property that was nationalized in the name of “the people” becomes the property of the most privileged at the top of the inner party, the “all-powerful exploiters and masters.” Milovan Dijilas, New Class: An Analysis of the Communist System 47 (1957). The same point is made in George Orwell’s book Animal Farm (1945).

“The President, Vice President, and all civil officers of the United States shall be removed from office on impeachment for, and conviction of, treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors.” Art. II §4.

The constitutional system of elections makes a president removable by the people every four years. In addition, a president may be removed during his term if he is impeached by the House and then convicted by the Senate. In 1974, President Richard Nixon resigned when facing certain impeachment and conviction because of his crimes, including the coverup of an attempted burglary, directed by Nixon’s staff, of the Democratic National Committee office at the Watergate office complex.

But there was no way to remove Mao, even when, as in the Great Leap Forward or the Cultural Revolution, the majority of the people, and even the majority of the CCP elite, thought that he was leading the nation into ruin. Like a bad Roman Emperor, Mao could only be removed by force.

In 1971, Mao began plotting to get rid of defense minister Lin Biao. Lin’s son began organizing a coup against Mao. The plan was to bomb Mao’s train in September 1971, when he would be returning from a trip to southern China to shore up support from the army generals there for Mao’s plan to remove Lin.

But Mao, knowing he was widely hated, often changed his travel plans at the last minute, as a security precaution. This time, the last-minute change saved his life. Lin Biao and his family tried to flee to Mongolia, dying in a plane crash on September 13, 1971.

“The judicial power of the United States shall be vested in one Supreme Court, and in such inferior courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. The judges, both of the Supreme and inferior courts, shall hold their offices during good behavior, and shall, at stated times, receive for their services a compensation, which shall not be diminished during their continuance in office.” Art. III §1.

“The trial of all crimes, except in cases of impeachment, shall be by jury.” Art. III §3.

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy the right to a speedy and public trial by an impartial jury of the state and district wherein the crime shall have been committed, which district shall have been previously ascertained by law, and to be informed of the nature and cause of the accusation; to be confronted with the witnesses against him; to have compulsory process for obtaining witnesses in his favor; and to have the assistance of counsel for his defense.” Amendment VI.

The U.S. Constitution guarantees the right to jury trial, with fair trial procedures, such as the right to counsel, public proceedings, and the right to cross-examine witnesses. Federal judges hold their positions until they choose to retire, and they cannot be removed for political reasons.

Under Mao, “judicial reform” purged judicial officers and ensured that a puppet judiciary would never err on the side of lenience against dissidents. Courts ceased to exist as independent finders of fact. They became administrative processing units for predetermined sentences. Entirely under the thumb of the CCP, judges merely pronounced the severe sentences that CCP officials had already decided. In cases where the law was not clear, judges were required to follow the Central Party line. According to the CCP official newspaper, People’s Daily, the accused were “presumed to be guilty. . . . Giving the accused the benefit of the doubt is a bourgeois weakness.”

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech or of the press, or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.” Amendment I.

No government-established religion, and free exercise of religion

As soon as the communists seized power, they began suppressing some religious organizations and bringing the rest under state control. Religious organizations could exist only as entities subordinate to and directed by the CCP. Soon, the government began to attempt to exterminate religion entirely. While atheism was the official communist belief, the party recognized that religion made people harder to control, as the faithful recognized a higher power than the CCP.

Today’s China is little different. Tibetan Buddhists, Uighur Muslims, and Falun Gong face the worst persecution. Christian denominations are allowed to exist only as state-controlled entities.

Mao despised religion. When Tibet’s Dalai Lama visited Mao in Beijing in 1954, Mao told him, “I understand you well. But of course, religion is poison. It has two great defects: It undermines the race, and secondly it retards the progress of the country. Tibet and Mongolia have both been poisoned by it.” Dalai Lama, My Land and My People 117-18 (2006).

Mao always wanted to be the center of attention. He didn’t like the Chinese national anthem, March of the Volunteers, which had been adopted by the CCP in 1949. It had originally been a song for people of all political persuasions who fought the Japanese invasion of China of 1933-45. During the Cultural Revolution, Mao put the national anthem author in prison, where he died. Although Mao did not formally change the national anthem, for almost every occasion that the national anthem would be played, Mao made the state media (the only media) instead play a song about him, The East Is Red.

“The East Is Red (Dongfang hong):

From China comes Mao Zedong.

He strives for the people’s happiness,

Hurrah, he is the people’s great saviour!

Chairman Mao loves the people,

He is our guide to building a new China.

Hurrah, lead us forward!”

For schoolchildren, a soon-to-be pervasive new song was composed in 1966: “Father is dear, mother is dear, But not as dear as Chairman Mao.”

Under German regime of the National Socialist German Workers Party (“Nazi” for short), people were required to say “Heil Hitler” rather than “Good morning” or “Hello.” The same became true with “Long Live Chairman Mao”—literally, “Chairman Mao ten thousand years” (Mao zhuxi wansui). One man was executed for saying that Chairman Mao would not actually live ten thousand years.

With Mao’s blessing, the military (the “People’s Liberation Army,” PLA) began establishing a new religion for China. Starting in the latter part of 1967, most nonwork time was taken up by mandatory nightly assemblies where people had to discuss their personal behavior in light of Mao Zedong Thought. Then came the 1968-69 campaign of “Three Loyalties” and “Four Boundless Loves” that everyone was supposed to feel for Chairman Mao.

Statues and shrines of Mao were erected everywhere. Busts or pictures of Mao were mandatory home religious items.

Although there was good money to be made, painters often declined the opportunity to paint a Mao icon, since the artist would be scrutinized and punished for the slightest inadvertent sign of insufficient veneration.

Upon arising in the morning, everyone had to face their home Mao shrine and “ask for instructions.” The day ended with “reporting back in the evening.” Mao replaced the “kitchen god” of Chinese folk culture. In other aspects Mao was portrayed as the sun god.

Life was structured around Mao and his words. Before every meal, people had to say grace: “Long live Chairman Mao and the Chinese Communist Party.”

Maoist life encompassed the body as well as the mind. Instead of normal sports, the new exercise routine was “quotation gymnastics”—a set of group exercises in which participants shouted Mao quotes related to the motions. For example, in the third set of exercises, the leader would yell “political power grows out of the barrel of a gun.” The exercisers would make nine thrusting and stabbing motions with imaginary bayonets.

Even more common were “loyalty dances,” in which individuals or groups stretched their arms to show their “boundless hot love” for Mao, sometimes worshipping him as the sun. The PLA enforcers labeled any nonparticipant in the Mao rites as an “active counterrevolutionary.”

People began reporting miracles such as healing of the sick and attributing them to Mao. Communist temples were erected, based on the historic model of ancestral temples. When buying a Mao item in a store, one could not use the common word for buying, mai; instead one would use the polite verb actress Jiang Qing, previously reserved for the purchase of religious items.

Freedom of speech and freedom of the press

When the communists were fighting to overthrow the Republic, they promised freedom of speech for everyone. As soon the Communists seized power, all nongovernment newspapers were closed.

All radios were confiscated, so no one could hear news from the outside world. The confiscation of radio transmitters ensured that people could not communicate with each other at a distance.

All mail was surveilled, and the contents were put in the secret files that the government kept on everyone.

Once people saw what communist rule was like, many people burned their book collections, because possession of a book—even an apolitical book—that was not based on communist ideology might result in the owner being labeled a “counterrevolutionary” and sent to a slave labor camp.

During the Cultural Revolution, the rage mobs pillaged libraries and burned books in huge outdoor bonfires, reminiscent of similar book burnings in Nazi Germany. The Nazi book burners mainly targeted books by Jewish authors, but Mao’s mobs were more ambitious. Any book that was not communist—such as books of ancient poetry—was put to the torch. Many rare historic manuscripts were destroyed.

Mao’s fourth wife, the former actress Jiang Qing, took a special interest in the performing arts. In China, opera had always been entertainment for the masses (as it was in the United States in the nineteenth century) and not solely for a highly educated audience (as it is in the U.S. today). Madame Mao banned all classical works of performing art. The only works that could be performed were post-1949 “model” pieces of crude communist propaganda. That amounted to five operas, two ballets, and one symphony. In the privacy of her palaces, Madame Mao enjoyed a much broader selection of entertainment, including private screenings of Western movies.

During the Cultural Revolution, simply being educated, or an intellectual, or able to speak a foreign language could be cause enough to be killed, tortured, or put into forced labor.

From about March 1968 to April 1969, even the most mundane conversation had to be centered on Mao. If a peasant walked into a store, the clerk was supposed to say “keep a firm hold on grain and cotton production,” and the peasant would reply “strive for even greater bumper crops.” If the customer was a student, the clerk would say “read Chairman Mao’s books,” and the student would answer “heed Chairman Mao’s words.” As one historian observes, “The Cultural Revolution is perhaps the time in the twentieth century when language was most separated from meaning. . . . If you do not mean what you say, because what you say has no meaning beyond the immediate present, then it is impossible to imbue language with any system of values. . . . This led to the overall moral nullity of the Cultural Revolution during its most manic phase.” Rana Mitter, A Bitter Revolution: China’s Struggle with the Modern World 209 (2004).

Or as George Orwell wrote about a fictional totalitarian government very similar to communism, “The intention was to make speech, and especially speech on any subject not ideologically neutral, as nearly as possible independent of consciousness.” George Orwell, Appendix: The Principles of Newspeak, in 1984 (1990) (1949).

Right to petition the government for redress of grievances

Of course there was no such right in Mao’s China, especially during the Cultural Revolution. Sending the government a critical petition would lead to every signer being imprisoned, tortured, sent to slave labor camp, or executed.

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Wang Rongfen, who was studying German at the Foreign Languages Institute, observed the similarities between Mao’s first Cultural Revolution rally for a crowd at Tiananmen Square and Hitler Nuremberg rallies. She sent Chairman Mao a letter: “the Cultural Revolution is not a mass movement. It is one man with a gun manipulating the people.” He sent her to prison for life. In prison, she was manacled full-time, and the manacles bore points to dig into her flesh. She had to roll on the floor to eat. She was released in 1979, three years after Mao’s death, with her spirit unbroken.

Right of Assembly

The textual right of assembly is related to the implied right of association. As the U.S. Supreme Court has recognized, the right of association is implied by the other First Amendment rights, and is necessary to their exercise.

Under the CCP, no associations could exist except those under government control. No assemblies on political matters were allowed, except those demanded by the government.

But when Premier Zhou Enlai died in January 1976, huge, spontaneous, and unauthorized crowds assembled to mourn him. The crowds considered him relatively less totalitarian and oppressive than Mao. Unlike the Tiananmen rallies of the early Cultural Revolution, which originated from the top down, the crowds that gathered to mourn Zhou expressed people power. “The country had not witnessed such an outpouring of popular sentiment since before the communists came to power in 1949.” Li Zhusui, The Private Life of Chairman Mao 611 (Tai Hung-Chao trans. 1994).

While there were demonstrations at over 200 locations throughout the country, the flashpoint was in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square, which saw the largest spontaneous demonstration ever in China. On April 4, Tomb-Sweeping Day (Qing Ming), a traditional day for honoring one’s ancestors, an immense crowd gathered at the Monument to the People’s Martyrs in Tiananmen Square. Erected in 1959, the monument honored Chinese revolutionary martyrs from 1840 onward.

That night, the Tiananmen assembly was attacked by the Capital Militia Command Post (a/k/a the “Cudgel Corps”). According to one report, it later took hundreds of workers to scrub off all the blood.

“A well-regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed.” Amendment II.

The Second Amendment ensures that the government will never have a monopoly of force. As Americans knew from recent history in Europe and from ancient history, people who were first disarmed were often tyrannized later.

The Chinese Communist Party was aware of similar lessons of history. In a 1938 speech, Mao explained, “Our principle is that the Party commands the gun, and the gun must never be allowed to command the Party. . . . According to the Marxist theory of the state, the army is the chief component of state power. Whoever wants to seize and retain state power must have a strong army.” Problems of War and Strategy (Nov. 6, 1938).

In 1949, one of the new regime’s “first acts” was “to confiscate weapons.” Jung Chang & Jon Halliday, Mao: The Unknown Story 424 (2005). Homes were inspected to “search for forbidden items, from weapons to radios.” Frank Dikötter, The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution 1945-1957, at 45-46 (2013).

By ensuring that all the people could be armed, the Second Amendment aimed to ensure that the militia would be drawn from all people. If the government were allowed to disarm people, then instead of a general militia of the people, there would be a “select militia” of the government’s favorites and toadies. At the Virginia Convention for ratifying the U.S. Constitution, George Mason had warned that a select militia would “have no fellow-feeling for the people.” (June 14, 1788).

As the U.S. Supreme Court noted, in England, the despotic Stuart kings in the seventeenth century had used “select militias loyal to them to suppress political dissidents, in part by disarming their opponents.” District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 592 (2008). Further, said the Court, the Second Amendment was enacted in part to assuage fears that the U.S. government “would disarm the people in order to impose rule through a standing army or select militia.” Id. at 588.

Under Mao, a select militia was the instrument for forcing most of the population into de facto slavery. In the 1958-62 Great Leap Forward, the select militia became the instrument that caused the deaths of over forty million people from famine.

In a nation of over 600 million people, the select militia comprised fewer than 2 percent of the population. Unlike in the American system, militia arms were not personally owned but were usually centrally stored and guarded.

According to a political refugee interviewed in Hong Kong in the 1950s, in a farm commune of 15,000 families, there would be about 1,500 militiamen, chosen from the politically correct, who would have rifles. Of these there was “a further selection of 150 super-reliable men whose rifles are always loaded.” Suzanne Labin, The Anthill: The Human Condition in Communist China 104 (Edward Fitzgerald trans., Praeger 1960) (1st pub. in France as La Condition Humaine en Chine Communiste (1959)). “Otherwise ammunition is kept at a central armoury guarded day and night by special police armed with machine-guns. As an extra precaution the personnel of this guard is changed every two months.” Id. A hundred and fifty always-armed males could control 15,000 families.

“They would turn out to be crucial in enforcing discipline, not only during the frenzy to establish communes, but throughout the years of famine that lay ahead.” Frank Dikötter, Mao’s Great Famine: The History of China’s Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-1962, at 182 (2010). “[L]ocal militia were a critical ingredient in the CCP’s consolidation of power in the countryside.” Elizabeth J. Perry, Patrolling the Revolution: Worker Militias, Citizenship, and the Modern Chinese State 182 (2007).

“The militia movement and a small corps of trained fighters brought military organization to every commune. All over China farmers were roused from sleep at dawn at the sound of a bugle and filed into the canteen for a quick bowl of watery rice gruel. Whistles were blown to gather the workforce, which moved in military step to the fields. . . . Party activists, local cadres and the militia enforced discipline, sometimes punishing underachievers with beatings.”

Dikötter, Famine, at 50. “Militiamen spearheaded the countless mobilization campaigns that were the hallmark of Mao’s rule. They enforced universal participation by all members of the factory or village, dragged out or designated targets of struggle [persons targeted for persecution], and monitored mass meetings.” Perry, at 191.

A case study of the remote village of Da Fo, located on the North China Plain, details the operation of the select militia. There, guns had been confiscated in 1951 (later than the general confiscation in 1949, perhaps because of the village’s isolation). Over the course of the war against the Japanese invasion and then the final phase of the civil war (1945-49), the high-quality leaders of the Da Fo communist militia had been moved elsewhere, to positions of greater responsibility. The militiamen left behind were the dregs of society. “Villagers remember them as poorly endowed, uneducated, quick-tempered, perfidious hustlers and ruffians who more often than not operated in an arbitrary and brutal political manner in the name of the Communist Party.” Ralph A. Thaxton, Jr., Catastrophe and Contention in Rural China: Mao’s Great Leap Forward: Famine and the Origins of Righteous Resistance in Da Fo Village 329 (2008).

There were no rules against them exploiting or coercing peasants. To the extent that the national government provided subsidies, the militia took them. The Da Fo militia had 30 guns and kept the crop fields under a four-man armed guard day and night, to prevent peasants from obtaining food.

“The militia was a repressive institution, and Mao needed it to press the countless rural dwellers who were resisting disentitlement by the agents of the people’s commune.” Id. “These men were practically the perfect candidates to tear apart civil society and destroy human purpose. . . . [T]hey had a lot in common with the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia, with Ceauşescu’s militias in Transylvania, and with the Janjaweed in the Darfur region of Sudan. In rural China of the late 1950s, as in these other killing field environments, such men were backed by state power.” Id. at 330.

The militia and the communist party cadres carried large sticks they used to beat the peasants. The frontline enforcers were under orders from their superiors to administer frequent beatings, and those who failed to do so were punished. “A vicious circle of repression was created, as ever more relentless beatings were required to get the starving to perform whatever tasks were assigned to them.” Dikötter, Famine, at 299.

Without the select militia, “surely the famine’s death rate would not have been so high.” Thaxton, at 331. Because of the select militia, peasants suffered “socialist colonization, subhuman forms of labor, and starvation.” Id. at 334.

Tibet

The Chinese Communist army invaded eastern Tibet in 1949 and central Tibet in 1951. At first, they ruled relatively mildly, while they worked hard at building a transportation infrastructure for permanent military occupation. But in 1956, the Chinese announced gun registration, which the Tibetans accurately foresaw as a step towards gun confiscation. In 1957, the CCP demanded that Tibetans surrender all their firearms.

Tibet was a universally armed nation. Every man was expected to have a firearm and be proficient with it. The Tibetan Buddhist monasteries had large arsenals. Even the poorest beggar would at least have a large knife.

As the Dalai Lama later recalled, when he heard about the gun confiscation order, “I knew without being told that a Khamba [Eastern Tibetan] would never surrender his rifle — he would use it first.” Roger Hicks & Ngakpa Chogyam, Great Ocean 102 (1984) (authorized biography).

The historically fractious Tibetan tribes united in a national resistance movement, the Chushi Gangdruk. For a while, they drove the Chinese out of most of Tibet, and liberated hundreds of thousands of square miles.

Yet although the Tibetan volunteers were, man-for-man, vastly superior fighters to the Chinese conscripts, the Chinese eventually wore down the Tibetan resistance through sheer force of numbers, just as centuries before barbarians in Europe had overwhelmed the Roman Empire’s legions.

The Tibetan resistance movement did make it possible for 80,000 Tibetans, including the Dalai Lama, to escape to India and Nepal, where they have kept the Tibetan Buddhist religion alive, free of CCP domination, and have continued to inform the world about the CCP’s colonialism and genocide in Tibet.

“No Soldier shall, in time of peace be quartered in any house, without the consent of the Owner, nor in time of war, but in a manner to be prescribed by law.” Amendment III.

Unlike some of the bad monarchs in England and France, Mao did not force families to let soldiers live in their homes. Rather, Mao forced people to live in soldiers’ homes, as prisoners under constant armed guard.

Starting in the Great Leap Forward, the government seized all farmland and forced people into communal labor. In many communes, families had to leave their homes, live in sex-segregated barracks, and eat in mess halls. Husbands and wives were allowed one short conjugal visit per week. This was consistent with Marxism, which boldly demanded “Abolition of the family!” Karl Marx, Communist Manifesto 24 (Samuel Moore & Friedrich Engels trans. 1888) (1848).

“The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched and the persons or things to be seized.” Amendment IV.

Starting in 1955-56, the CCP ordered that people allow home inspections at any time. This was part of a household registration system that also required people to reside in the registered place permanently, unless they were given government permission to move. People could travel only when issued a permit, had to register when staying somewhere else overnight, had to register their own house guests, and had to report on the content of conversations with guests.

All postal mail could be secretly opened by the government, its contents recorded in the government’s secret files on every person, to accumulate material for potential later use against the writer.

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s mobs, the “Red Guards,” searched house-to-house for concealed arms, books, religious items, gold coins, and evidence of disloyalty. If something was found, the victims were tortured. “Every night there were terrifying sounds of loud knocks on the door, objects breaking, students shouting and children crying. But most ordinary people had no idea when the Red Guards would appear, and what harmless possessions might be seen as suspicious. They lived in fear.” Frank Dikötter, The Cultural Revolution: A People’s History, 1962-1976, at 86-90 (2016). Many people pre-emptively destroyed their books and artwork, lest the Red Guards discover them. Ordinary thieves posed as Red Guards to get in on the looting.

“[N]or shall any person be subject for the same offense to be twice put in jeopardy of life or limb; nor shall be compelled in any criminal case to be a witness against himself, nor be deprived of life, liberty, or property without due process of law; nor shall private property be taken for public use without just compensation.” Amendment V.

The prohibition of “double jeopardy” means that if a person is tried for alleged crime and acquitted, the government cannot prosecute the same person a second time for the same offense. This was irrelevant under Mao, since persons who were accused were always convicted the first time.

While the Fifth Amendment forbids compelled self-incrimination, self-incrimination was mandatory under Mao. If an arrested person did not confess to whatever crimes she was accused of, she would be tortured until she did.

The Takings Clause means that government must pay compensation when it takes a person’s property. But under Mao, property could be taken at any time. Some people had no property at all. For example, starting with the Great Leap Forward in 1958, the peasants forced to live in barracks on the collective farms were not allowed to own even a spoon.

The communists had won the revolution in part because they had promised to give land to the peasants. The communists did so in the years immediately after the revolution. Then starting in 1958, the land was taken by the government. The peasants were turned into serfs—forbidden to leave the land and forced to labor under armed guard to produce crops, most of which the government would take without compensation.

In the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s rage mobs roamed the streets, attacking women for bourgeoise behavior such as wearing dresses or having long hair. Poor street peddlers, barbers, tailors, and anyone else participating in the non-state economy were attacked and destroyed. Many of them were ruined and became destitute.

“Excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted.” Amendment VIII.

The system of bail allows a person who has been arrested for crime to be released from jail pending trial, if the person posts a bond to ensure that he will appear in court for trial. Under communism, once a person is arrested, the person may simply “disappear,” never to be seen in public again.

While the Eighth Amendment prohibits torture, torture was a common tool of the Mao regime. Soon after the communists seized power in 1949, their “land reform” program encouraged peasants to torture and then kill small farmers and landlords. If Mao decided that a high-ranking official was now an enemy, he would have the official tortured in front of an assembly of the communist elite.

In the Cultural Revolution, Mao’s rage mobs roamed the streets with leather belts with brass buckles, which they used to beat their targets senseless, often inflicting severe injury. Sometimes the victims were forced to lick their blood up from the street. Any pedestrian could be accosted by Red Guards, ordered to recite quotations from Chairman Mao, and then tortured on the spot for not having memorized enough of them.

The Cultural Revolution also brought a savage campaign of genocide and torture of the minority Mongol population, living in north-central China. Ethnic minorities in other border regions received similar treatment.

A new round of purges began in 1969 and ran through 1971, based on a supposed “May Sixteenth” conspiracy from 1966. This was the date that a circular had announced the creation of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, which would publicly unleash the Cultural Revolution several days later. Supposedly, May 16 was also the debut of a secret plot against Premier Zhou Enlai. Although Zhou was himself a member of the Central Cultural Revolution Group, there were others in the group, including Mao’s wife, who hated him and plotted against him. Whatever the intrigue at the top, the persecution of “May Sixteenth elements” did not target Madame Mao but instead large numbers of people who had no plausible connection to any conspiracy; they were tortured into confessing to having joined a conspiracy that they had never heard of before they were arrested.

Meanwhile, in rural areas, where the Cultural Revolution was less intense, the local militias, aware of all the killing and torture going on in the towns and cities, decided to demonstrate their loyalty by going on their own spontaneous murder and torture sprees.

The victims were not participants in Cultural Revolution politics. Rather, the targets were the “Four Types”—who since 1949 had always been easy targets for attack. These included former landlords, anyone who had owned a small business before the revolution, anyone who was claimed to be a noncommunist, and any “bad element” who had supposedly deviated from the CCP orthodoxy of the moment.

Victims were typically denounced in public show trials that everyone in the village had to attend. Some victims were executed in plain sight to spread terror. Execution methods involved firearms, beating and torturing people to death (always common under Mao), or imaginative procedures, such as marching victims off a cliff.

“The enumeration in the Constitution of certain rights shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.” Amendment IX.

“The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the states, are reserved to the states respectively, or to the people.” Amendment X.

The U.S. constitutional system is based on the sovereignty of the people. The people delegate some powers to the federal government, via the Constitution. The Ninth Amendment makes it clear that the Bill of Rights is not an exclusive list of the people’s retained rights. The Tenth Amendment affirms that the people and their state governments retain all powers that were not delegated to the federal government.

Under communism, the people have no “retained” rights or “reserved” powers. The omnipotent sovereign is the communist party. Under Maoism, the only purpose of human existence was to serve Mao.

Dave Kopel is Research Director of the Independence Institute; an Adjunct Scholar with the Cato Institute, in Washington; and adjunct Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. His website is www.davekopel.org. He is a regular panelist on Colorado Public Television’s “Colorado Inside Out” and a columnist for the Reason magazine on the Volokh Conspiracy law blog.

Dave Kopel is Research Director of the Independence Institute; an Adjunct Scholar with the Cato Institute, in Washington; and adjunct Professor of Constitutional Law at the University of Denver’s Sturm College of Law. His website is www.davekopel.org. He is a regular panelist on Colorado Public Television’s “Colorado Inside Out” and a columnist for the Reason magazine on the Volokh Conspiracy law blog.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

Mr. James Ingram

BlogMr. James Ingram was Constituting America Founder, actress Janine Turner’s, beloved 5th grade teacher, who instilled in Janine a love of our founding fathers, through the 5th grade’s production of 1776.

Mr. Ingram was honored as Constituting America’s Constitutional Champion in 2011 and was a beloved and active member of our Education Advisory board.

Mr. Ingram’s full obituary is below.

NORTH RICHLAND HILLS – James Ingram, 72, passed away on Saturday, March 2, 2024.

Graveside Service: 10 a.m. Saturday, March 9, 2024, at Mount Olivet Cemetery with Jinx Ingram Thompson to officiate. Elizabeth Hatley, a dear friend, will deliver the eulogy. Visitation: 5 to 7 p.m. Friday, March 8, 2024, at Mount Olivet Chapel in the Sandburg Suite.

James was born in Fort Worth. He was the son of, James and Juanita Ingram. James accepted Christ as his personal Savior at a young age. He prayed daily and maintained a positive spirit. His cousins, Jinx and Betty, were like sisters to him. They had many great times including U.S.A. and world travel experiences.

James graduated from Texas Wesleyan University with a Bachelor of Science degree. He obtained a Master’s in Education degree from Texas Christian University.

His lifelong, devoted career encompassed 34 years as an elementary fifth grade teacher at Eagle Mountain Elementary. He enjoyed the challenge of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet in a modified version on the stage with his fifth grade Language Arts classes. He also produced musicals with his students early in his career. The Eagle Mountain-Saginaw I.S.D. school board named the school stage in his honor when he retired.

Other educator honors included: 1995-1996 District-wide Elementary Teacher of the Year, Peer Professional, PTA Life Membership Recipient, PTA Extended Service Award, and Saginaw Chamber of Commerce Educator of the Year.

James appeared on television’s Disney’s American Teacher Awards. He was selected by actress, Janine Turner, a wonderful former student, as her favorite teacher. Furthermore, Ms. Turner recognized him as “The Constitutional Champion Teacher at the “Constituting America” gala.

His involvement with Miss Texas Pageant included Board of Trustees member and Awards Ball Set-Up committee chairman. James was inducted into the Miss Texas Hall of Honor for his pageant work.

James was a season ticket holder with dear friends for the Fort Worth Symphony Pops, Texas Ballet Theater, and Theatre Arlington. B. J. Cleveland, former artistic director at Theatre Arlington, was a talented former student.

Trips to the Texas Rangers baseball games were a highlight. The “good times” were highlighted with his Bunco groups of special friends. The Olive Garden, Chili’s, Babe’s Restaurant, Saltgrass, and Abuelo’s were his favorite restaurants. James enjoyed reading best sellers and viewing the Oscar-nominated movies. Morning walks with his mall buddies at the NE Mall and Grapevine Mills Mall, started each day with special conversations and many smiles. Pilgrimages to Scarborough Faire in Renaissance costumes with his Bros.-in-Hose provided majestic experiences for James and friends.

Surgeries were a challenge later in life. These included open-heart surgery, two hernia surgeries, six leg surgeries, cataracts surgeries, skin cancer surgery and gallbladder surgery. God’s Grace saw James through these times.

Survivors: All from Fort Worth

Cousin, Jinx Ingram Thompson

Cousin, Betty Evans

Second Cousin, Kim, and her 3 children

Second Cousin, Josh and wife, Laurie and their 5 children

Cousin, Tommy Freeman, and his 3 children

To plant Memorial Trees in memory of James Arnold Ingram, please click here to visit our Sympathy Store.

Maureen Quinn

BlogIn loving memory of our dear friend, Anne Maureen Quinn. Maureen entered this life on September 25, 1956 and passed away December 14, 2022. Maureen was a bright light who shone in all of our lives.

We were blessed to have Maureen’s beautiful voice narrate many of our 90 Day Studies. She also submitted our We The Future Contest winners’ films into film festivals, achieving over 118 film festival acceptances for our winners over her time with us. In Maureen’s memory, we have named our We The Future short film category after her.

Maureen was a talented writer, inspirational life coach and sought after voice talent in Hollywood, but most of all, she was a treasured friend to all of us who had the blessing of knowing her and working side by side with her over the years.

Please join us in leaving your remembrances of Maureen here on our page.

Conclusion: Preserving the First Principles of the American Founding

90 in 90 2023, Christopher C. Burkett, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog Essay 90: Conclusion: Preserving the First Principles of the American Founding – Guest Essayist: Chris Burkett, 2023 - First Principles of the American Founding, 13. First Principles of the American Founding, Christopher C. Burkett, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day StudiesEssay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Does the United States today resemble the nation envisioned by the American Founders? Have we lived up to the political and constitutional principles they believed are so important for maintaining a free society and remaining a self-governing people? Have we as a people done a good job of preserving those principles by educating and reminding each generation on their importance? Constituting America’s 90-Day Study on “First Principles of the American Founding” should help each of us, as citizens, think about the first two questions in a more enlightened and informed way – and certainly goes far in ensuring that the third question is answered in the affirmative.

In this series of essays, written by exceptionally thoughtful thinkers, teachers and scholars, we can discern how insightful the American Founders were in recognizing and articulating the first principles upon which the nation of America was founded. From ideas identifying the basis of rights in nature rather than tradition, to constitutional principles that established a limited government, to foreign policy principles meant to promote justice with other nations, these essays allow us to glean in a more capacious way the overarching ideas that informed who we were meant to be as a people and a nation.

These essays reveal that Americans, and especially the Founders, had learned extensively from the careful study of history. Born of English tradition, Americans gradually came to develop their own identity – one might even say “mind,” as Thomas Jefferson called it. Separated from Great Britain and largely left alone for decades, American colonists lived in relative freedom and came to establish local governments and social institutions that complemented their understanding of rights and liberties. They frequently heard these ideas of individual liberty and limited government reinforced in their churches, newspapers, shops, and businesses. The essays in the 90-Day Study, as a whole, show the story of how Americans became one people united by common principles.

The American Revolution was, in more than one sense, a test of those principles. Should the Revolution fail, the principles of liberty and self-government might be lost forever. It was also a test in the sense that Americans found themselves in the position of having to accomplish a political separation and wage a war in accordance with the very principles they declared to be self-evidently true. Winning the war and gaining independence seemed to many, including George Washington, nothing short of miraculous. Having accomplished this, Americans next found themselves having to apply the principles of the Declaration of Independence to the creation of a government that would fulfill the demands of justice both at home and toward foreign nations. In other words, Americans had to learn how to act like a nation – and this is when Americans applied and thought even more deeply about the meaning of their founding principles.

Domestically, Americans faced the great difficulty of establishing a republic, based on consent, to replace the traditional form of monarchy that had prevailed throughout most of human history. The challenge facing the Framers of the United States Constitution was how to frame a government that was sufficiently powerful to secure the natural rights of American citizens, but that was also sufficiently checked to prevent it from abusing and violating these rights and liberties. Another great challenge was to find constitutional ways of obligating America’s government to secure American sovereignty and independence, and to respect the independence and sovereignty of other nations. The essays in this 90-Day Study reveal that, to fulfill these ends, knowledge of fundamental principles proved to be the guiding star for the Framers of the Constitution, and the standard by which American citizens could judge the justice or injustice of acts of government even after the Constitution had been ratified.

In the end, these essays bring to the fore the Founders’ view that without civic virtue, no government – not even America’s own Constitutional government – can succeed. Local political participation can never be replaced by national administration without some cost to individual liberty; and despite the best efforts of the Framers of the Constitution, civic awareness and engagement is still necessary to check laws and policies that are contrary to the principled purposes of government. All of this reinforces why the Founders believed that a proper civic education of the American people was so critical – an education that informs them of both their rights and duties. This 90-Day Study, as a whole, aims to fulfill that crucially important purpose of the American Founders.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Upholding the Principle of Free Civil Discourse and Public Debate Without Censorship

90 in 90 2023, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Gary Porter Essay 87: Upholding the Principle of Free Civil Discourse and Public Debate Without Censorship – Guest Essayist: Gary Porter, 2023 - First Principles of the American Founding, 13. First Principles of the American Founding, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Gary PorterAmerican government, as President George Washington notes, is to be based on opportunities to discuss political and policy issues by reflection and choice rather than by accident and force:

[I]f Men are to be precluded from offering their Sentiments on a matter, which may involve the most serious and alarming consequences, that can invite the consideration of Mankind, reason is of no use to us; the freedom of Speech may be taken away, and, dumb and silent we may be led like sheep, to the Slaughter. – George Washington, Speech to the Officers of the Army at Newburgh, the Newburgh Address, March 15, 1783.

The Articles of Confederation Congress had difficulty with the states meeting their funding requisitions during most of the Revolutionary War period. Ending the siege at Yorktown in General George Washington’s favor only made matters worse. With the British no longer posing a threat, the men of the Continental Army were ordered into bivouac at Newburgh, New York. Soon thereafter, Congress stopped paying them, as a “cost-saving” measure, and also stopped funding the soldiers’ pensions.

The conflict over this came to a head when an anonymous letter was circulated in Congress in which a threat was made: the Army would remove itself to “unsettled” western lands, leaving the states unprotected until such time as pay and funding resumed.

Commander-in-Chief General George Washington traveled personally to Newburgh, and in an emotional scene during which he apologized for having to use spectacles to read his prepared remarks said, “I have grown not only gray, but almost blind in the service of my country,” he convinced the officers and men to renew their trust in Congress. Washington noted that the anonymous letter was appropriate since, “[I]f Men are to be precluded from offering their Sentiments on a matter, … the freedom of Speech may be taken away, and, dumb and silent we may be led like sheep, to the Slaughter.”

“The Founders considered freedom of speech a fundamental natural right.”[i] At the same time, the right was also understood to not be absolute because during the early colonial period, “seditious words” were taken seriously and often prosecuted, as was blasphemy in most states.

When Patrick Henry proclaimed on May 29, 1765, that “Caesar had his Brutus, Charles the First his Cromwell and George the Third … may profit by their example,” he was indeed guilty of treason under English law. To “compass or imagine” the death of the King was one of the several crimes in the Treason Act of 1351, and Henry knew this. To the cries of “Treason” from some of the Burgesses in the room, Henry replied, “If this be treason, make the most of it.”

Christian thinker, G. K. Chesterton, said: “To have a right to do a thing is not at all the same as to be right in doing it.”[ii]

Sir William Blackstone agreed: “Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public…But if he publishes what is improper, mischievous, or illegal, he must take the consequence of his temerity.”[iii] Note that Blackstone refers here to “illegal” speech; the Treason Act would provide but one example.

But other founding era philosophers disagreed. French philosopher Baron de Montesquieu,[iv] in his acclaimed work, The Spirit of the Laws, wrote: “The laws do not take upon them to punish any other than overt acts. . . . Words do not constitute an overt act; they remain only an idea.”

Without freedom of speech during the period 1760-1776, there likely would have been no revolution leading to American independence. Based on the Founder’s experience, the British would have prohibited public speeches arousing the people to claim their freedom and the press would have been severely curtailed.

“Freedom of speech is a principal pillar of a free government; when this support is taken away, the constitution of a free society is dissolved, and tyranny is erected on its ruins. Republics and limited monarchies derive their strength and vigor from a popular examination into the action of the magistrates. An evil magistrate entrusted with power to punish for words, would be armed with a weapon the most destructive and terrible.”[v]

In ratifying the United States Constitution, Virginia, North Carolina and Rhode Island (both of which copied Virginia’s submission verbatim) all proposed a free speech amendment and James Madison included an amendment, which read: “That the people have a right to freedom of speech, and of writing and publishing their sentiments; that the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty, and ought not to be violated.”[vi] In successive House and Senate committees this was “wordsmithed” to the wording eventually placed within the Bill of Rights of the United States Constitution.

The Founders great emphasis on freedom of speech makes the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798 difficult to explain. Perhaps the expression “when the shoe is on the other foot” best captures Congress’s motivation to censor and suppress speech as the infant nation of America attempted to stay neutral in the on-again, off-again war between England and France. Americans were equally split on the question of which country the John Adams administration should support (even as both England AND France were both interdicting American shipping heading for their enemy’s ports). The Sedition Act made it illegal to make false or malicious statements about the Adams administration, specifically mentioning the President while conspicuously not mentioning the Vice-President. Criticism of Thomas Jefferson was therefore fair game, and certain “Adams-friendly” newspapers took great advantage of it.

So convinced they were of the unconstitutionality of the Acts, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison consented to drafting, respectively, the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions. These essays argued that the states have both a right and a moral responsibility to declare unconstitutional acts of the national government to be so and hold them to be null and void within their state.

The U.S. Supreme Court eventually found the Sedition Act to be constitutional in United States v. Thomas Cooper (1800).[vii] Congress had set the Alien and Sedition Acts to expire on March 3, 1801; the reason being was, the following day, a new President and Vice President would be inaugurated. Over a century later, President Woodrow Wilson’s administration would bring back the Alien and Sedition Laws (as the Espionage and Sedition Acts) as the U.S. entered World War I.

The Free Speech landscape had changed drastically by 1925 when the Court “incorporated” the Free Speech Clause into the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in Gitlow v. New York,[viii] creating an explosion of free speech cases based on state government actions, which continued thereafter.

Although the Free Speech Clause was intended to only restrict government actions, in the 1970s, the Supreme Court began deciding that commercial “speech” could also be regulated to some extent.[ix] Since that time, regulations on commercial advertising have become commonplace.

Eventually, the Court decided that certain types of “symbolic speech,” i.e. “speaking” through actions rather than words, should also be protected.[x] Over the years, the following are some examples of types of symbolic speech among those requiring protection:

Without freedom of speech, remaining steadfast to the principle of free civil discourse and public debate without censorship, America would likely be a very different place. “Freedom of Speech is the great Bulwark of Liberty; they prosper and die together.”[xi]

[i] Robert Natelson, The Original Constitution; What it Actually Said and Meant.”Apis Books Colorado Springs, CO, p. 212.

[ii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G._K._Chesterton

[iii] William Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 1769.

[iv] Montesquieu was the most oft-quoted political philosopher at the Constitutional Convention, after the Bible.

[v] Benjamin Franklin, On Freedom of Speech and the Press, Pennsylvania Gazette (17 November 1737).

[vi] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Bill_of_Rights

[vii] https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/sedition-case

[viii] https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/268/652

[ix] https://constitution.findlaw.com/amendment1/freedom-of-speech-for-corporations.html

[x] https://mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/1022/symbolic-speech

[xi] Trenchard and Gordon, Cato’s Letters, February 4, 1720.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Upholding the Principle of Amending the United States Constitution by the American People, Its Rightful Keepers

90 in 90 2023, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Gary Porter Essay 62: Upholding the Principle of Amending the United States Constitution by the American People, Its Rightful Keepers – Guest Essayist: Gary Porter, 2023 - First Principles of the American Founding, 13. First Principles of the American Founding, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Gary R. PorterAmending the Constitution Without Amending the Constitution

Article V of the United States Constitution describes that the only lawful methods, of amendment, are by its keepers, the American people. While that may have been the Framers’ intent, an unlawful method of amending the Constitution, through judicial activism, for example, usurps the legislative process of the American people when the courts are used as a legislature. Black’s Law Dictionary defines “judicial activism” as a “philosophy of judicial decision-making whereby judges allow their personal views about public policy, among other factors, to guide their decisions.”[1]

When the Supreme Court renders an opinion about a constitutional provision, that opinion–it is called an “opinion” and not a “law”–has traditionally assumed the status of the Constitution itself; since the Constitution is the Supreme Law of the Land (see Article VI), the American people and the federal government have given federal court opinions the same status: the law of the land. Nothing in the U.S. Constitution requires this, but that is the way America has operated as a people since the Constitution was ratified. Many distinguished men over the years have warned against this approach:

Thomas Jefferson: “[T]o consider the judges the ultimate arbiters of all constitutional questions [is] a very dangerous doctrine indeed and one which would place us under the despotism of an oligarchy.”

Andrew Jackson: “The opinion of the judges has no more authority over Congress than the opinion of Congress has over the judges.”

Abraham Lincoln: “[I]f the policy of the government upon vital questions affecting the whole people is to be irrevocably fixed by decisions of the Supreme Court…the people will have ceased to be their own rulers, having to that extent practically resigned their Government into the hands of that eminent tribunal.”

Is the U.S. Constitution “Alive?”

President Woodrow Wilson is credited with originating the concept of a “Living Constitution,” the idea that the Constitution must constantly be updated to reflect changes in the culture and mores of an evolving society. Who best to guide the “evolution” of the Constitution but the legal “scientists” of the federal courts? Why go through the arduous process of amending the Constitution through Article V when the Supreme Court is willing to issue an opinion which will have the same effect as a desired amendment? The Supreme Court has often been viewed as the “legislature of last resort.” Policies which have failed to gain majority acceptance in the Legislative Branch, whether state or federal, are instead “enacted into law” by the Judiciary.

The Anti-federalist called “Brutus”[2] warned: the “power in the judicial, will enable them to mould the government, into almost any shape they please.”

James Madison mentioned in Federalist 51 that the Constitution requires the government “to control itself.”[3]

Congress last proposed an amendment to the Constitution fifty-two years ago, in 1971, the Twenty-sixth Amendment. Scores of proposed amendments are introduced in Congress each session; a handful may make it out of committee; none have achieved a two-thirds vote on the floor in either chamber, or both chambers, since 1971.

Article V of the United States Constitution, on amending the Constitution, states that when two-thirds (34) of the state legislatures apply to Congress for an amendment convention, Congress shall convene one. Nothing in the Constitution describes how such a convention must operate, or the threshold within the convention for approving amendment proposals before they are transmitted for ratification, but there is ample historical evidence showing how such conventions of the states operated during the founding period and model rules for such a convention have already been composed and tested.[4]

Consider next the alternatives to amending the Constitution through an Article V convention:

The “Article V Question” is indeed controversial. Some opponents insist it will do more damage than good. Still, with arguments on both sides, correctly amending the Constitution remains in maintaining the principle that “the United States Constitution prescribes within the document the only lawful methods of amendment, by its keepers, the American people.”

[1] As quoted in “Takings Clause Jurisprudence: Muddled, Perhaps; Judicial Activism, No” DF O’Scannlain, Geo. JL & Pub. Pol’y, 2002.

[2] The identity of Brutus is unknown, but scholars have suggested he was either Melancton Smith of New York or John Williams of Massachusetts. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brutus_(Antifederalist).

[3] James Madison, Federalist No. 51, 1788, read at: https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed51.asp.

[4] https://conventionofstates.com/videos/official-convention-of-states-historic-simulation-live.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Principle of a United States Constitution Prescribing Within Itself the Only Lawful Methods of Amendments, by Its Keepers, the American People

90 in 90 2023, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Gary Porter Essay 61: Principle of a United States Constitution Prescribing Within Itself the Only Lawful Methods of Amendments, by Its Keepers, the American People – Guest Essayist: Gary Porter, 2023 - First Principles of the American Founding, 13. First Principles of the American Founding, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Gary R. PorterPrior to achieving statehood in March 1791, the Republic of Vermont placed a provision in their 1786 State Constitution. Every seven years, the people would elect a 13-person Council of Censors who would examine whether: “the Constitution has been preserved inviolate in every part, during the last septenary (including the year of their service;) and whether the legislative and executive branches of government have performed their duty, as guardians of the people, or assumed to themselves, or exercised other or greater powers than they are entitled to by the Constitution: they are also to inquire, whether the public taxes have been justly laid and collected in all parts of this Commonwealth–in what manner the public monies have been disposed of–and whether the laws have been duly executed.”[i] This Council would: “recommend to the Legislature the repealing such laws as appear to them to have been enacted contrary to the principles of the Constitution; these powers they shall continue to have, for, and during the space of one year from the day of their election, and no longer. The said Council of Censors shall also have power to call a Convention, to meet within two years after their sitting, if there appears to them an absolute necessity of amending any article of this Constitution which may be defective–explaining such as may be thought not clearly expressed–and of adding such as are necessary for the preservation of the rights and happiness of the people; but the articles to be amended, and the amendments proposed and such articles as are proposed to be added or abolished, shall be promulgated at least six months before the day appointed for the election of such Convention, for the previous consideration of the people, that they may have an opportunity of instructing their delegates on the subject.” (Emphasis added)

Laying on land claimed by both New Hampshire, New York and, at times, Canada, Vermont finally became an independent republic on January 15, 1777. It called itself the State of Vermont but failed to receive recognition by any country until admitted to the union on March 4, 1791.[ii] Because of its independency, Vermont was not invited to the Constitutional Convention in 1787. If it had been invited, would these ideas of constitutional review and revision have made it into the United States Constitution? If the U.S. Constitution had contained such a provision, what sort of amendments might have been ratified over these 234 years (as of 2023). And over these years, would the Constitutional “Council of Censors” find, repeatedly, that the Constitution had not “been preserved inviolate in every part”?

Amendment Under the Articles of Confederation

One of the chief defects of the Articles of Confederation, found in Article XIII, reads in part: “nor shall any alteration at any time hereafter be made in any of [these Articles]; unless such alteration be agreed to in a Congress of the United States, and be afterwards confirmed by the legislatures of every State.”[iii] (Emphasis added)

This requirement for unanimity among the states meant that the Articles would never be amended or otherwise improved. In his Vices of the Political System of the United States, James Madison’s “homework assignment” to himself, he fails to mention this flaw among the twelve “vices” he identifies; it could be that much of the “blame” for America’s moving to a new Constitution is due to this one defect. At the Constitutional Convention, Charles Pinckney said “it is to this unanimous consent [provision of the Articles], the depressed situation of the Union is undoubtedly owing. Had the measures recommended by Congress and assented to, some of them by eleven and others by twelve of the States, been carried into execution, how different would have been the complexion of Public Affairs? To this weak, this absurd part of the Government, may all our distresses be fairly attributed.”[iv]

In 1781, a proposal was made to amend the Articles of Confederation to give Congress the power to set an impost on goods. Rhode Island refused to approve the measure. As described in the notes of delegate James Madison, “[t]he small district of Rhode Island put a negative upon the collective wisdom of the continent.” Just as Rhode Island’s veto prevented the adoption of an impost in 1781, New York would be the sole state to obstruct a second impost attempt two years later.

Early in 1785, a Congressional committee recommended amending the Articles of Confederation to give Congress power over commerce. Congress sent the proposed amendment to the state legislatures; only a few states responded.

Later that year, in a letter to James Warren, George Washington, wrote: “In a word, the confederation appears to me to be little more than a shadow without the substance;..Indeed it is one of the most extraordinary things …that we should confederate for National purposes, and yet be afraid to give the rulers of that nation… sufficient powers to order and direct the affairs of the same.”[v]

In 1786, Charles Pinckney proposed a revision of the Articles. A committee debated the proposal and recommended granting Congress power over both foreign and domestic commerce, and empowering Congress to collect money owed by the states. By now, convinced that at least one state would disagree, Congress never sent the measure to the states. Given this history, it appeared to the Constitutional Convention delegates that something less than unanimity was required to amend the new Constitution they had drafted.

Amendment at the Constitutional Convention

Item seventeen of the Virginia Plan, introduced in the “Grand Convention” on May 29, 1787, stated: “Resolved. that provision ought to be made for the amendment of the articles of Union, whensoever it shall seem necessary;” There were many provisions of the Virginia Plan to discuss and debate. The delegates did not discuss a process of amendment until a month before the end of the convention.

The U.S. Constitution, Analysis and Interpretation website,[vi] provides this account of the debates over what became Article V of the new United States Constitution:

Alexander Hamilton … suggested that Congress, acting on its own initiative, should have the power to call a convention to propose amendments.[vii] In his view, Congress would perceive the need for amendments before the states.15 Roger Sherman took Hamilton’s proposal a step further, moving that Congress itself be authorized to propose amendments that would become part of the Constitution upon ratification by all of the states.16 James Wilson moved to modify Sherman’s proposal to require three-fourths of the states for ratification of an amendment.17 James Madison offered substitute language that permitted two-thirds of both houses of Congress to propose amendments, and required Congress to propose an amendment after two-thirds of the states had suggested one.18 This language passed unanimously.19

But on September 15, 1787, two days before the convention adjourned for the last time, Article V of the draft Constitution was again discussed. To that point, the approved wording gave all power to Congress to officially propose amendments, although the states could suggest them. Virginia’s George Mason rose and cautioned that: “No amendments of the proper kind would ever be obtained by the people, if the Government should become oppressive (as Madison wrote in his notes), as he verily believed would be the case.” Gouverneur Morris and Elbridge Gerry then moved to require a convention on application of two-thirds of the states and the motion passed “nem: con:” (unanimously). And this provided the alternate method of proposing constitutional amendments: a convention of the states. But notice the rationale for this alternate method of amendment: should Congress become oppressive.

The process of amendment placed in Article V was further debated in the state ratifying conventions, the records of Massachusetts,[viii] North Carolina[ix] and Virginia[x] particularly recording the concerns of delegates. Some convention delegates, like Virginia’s Edmund Randolph, who refused to sign the Constitution, even called for an amending convention[xi] to be immediately convened to fix the “deficiencies” in the Constitution before they went into operation, which would make them harder to correct. Madison thought the idea dangerous. Randolph’s suggestion never gained momentum and the Constitution was ratified by Virginia on June 26, 1788, four days after New Hampshire’s ratification “sealed the deal” because it was the ninth state to ratify, the number of states required by the new Constitution. Less than a year later, the new national government went into operation.

Amending the Constitution – Correctly

Article V of the United States Constitution contains two methods of proposing amendments and two methods of ratifying amendments. Congress, with a two-thirds vote of both chambers, can propose an amendment for ratification by the states and the states themselves, in a convention called for that purpose, can propose amendments for ratification. Over America’s history, all 27 current amendments have been proposed by Congress, none by a convention of the states.

Ratification of a proposed amendment can also take two forms: ratification by three-fourths of the several state legislatures (38) or ratification by three-fourths of state conventions held for that purpose, Congress may “propose” either method. Over America’s history, the later method of ratification has been used only once, to ratify the Twenty-first Amendment.

As many as five thousand amendments have been proposed in Congress since the Constitution went into effect in 1789 and only twenty-seven survived the high hurdle of committee discussions/votes followed by super majority floor votes in both chambers.