Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

“New England town meetings have proved themselves the wisest invention ever devised by the wit of man for the perfect exercise of self-government and for its preservation.” – Thomas Jefferson, 1816

“Local assemblies of citizens constitute the strength of free nations. Town-meetings are to liberty what primary schools are to science; they bring it within the people’s reach, they teach men how to use and how to enjoy it. A nation may establish a system of free government, but without the spirit of municipal institutions it cannot have the spirit of liberty.” – Alexis de Tocqueville, 1835

The concept of people openly gathering to discuss matters of public interest was developed among the ancient Greek city states in the 6th Century B.C. It became known as “Athenian Democracy” under the leadership of Pericles (461-429 B.C.) during Athens’ “Golden Age.” Participation was open to all adult free male citizens.

In actions that would be repeated throughout history, Athenian public meetings were suppressed to centralize government power. This occurred in 322 B.C. by the rulers of the Macedonian Empire, first Philip II and then his son, Alexander “the Great.”

Freedom of assembly vanished during the Roman Empire and the feudal states. People could still petition the chief, warlord, or king for grievances, but local democracy was lost.

Iceland rekindled community-based democracy in 930 A.D.

The Althing (Norse for “assembly field”) was an open area (near present day Reykjavik) reserved for the annual gathering to discuss and decide issues facing the community. The presiding official, Lögsögumaður (Norse for “Law Speaker”), stood on a central rock outcropping known as the Lögberg (Norse for “Law Rock”). He established the procedures for the Althing and declared decisions after open discussion and voting. All free men had the right to attend and participate.

The Althing lost its authority when Iceland was annexed by Norway in 1262.

In 1231, the freedom of assembly, and early federalism, arose among the various independent regions (Cantons) in Switzerland. The Landsgemeinde (German for “cantonal assembly) was established as a system of direct democracy, open voting, and majority rule among the communitas hominum (Latin for “the community of men”). This terminology was to emphasize that it was an assembly of all citizens, not just the elite.

Citizens of the Swiss Cantons fiercely defended their assemblies. In 1499, they defeated the forces of Emperor Maximillian I, the Holy Roman Emperor, at the battle of Dornach. They retain their system to this day.

The practice of holding town meetings in Colonial America developed from 17th Century English “vestry” meetings. These meetings allowed parishioners to discuss and decide issues relating to their local parish. These became integral to New England communities in the mid to late 1600s. Their agendas ranged beyond church governance to community matters.

In 1691, the Colonial Parliament (General Court) of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts passed a Charter that declared that final authority on bylaws rested with town meetings. In 1694, the Massachusetts General Court granted town meetings the authority to appoint assessors. In 1715 it granted town meetings the right to elect their own presiding officers (moderators) instead of relying on outside appointees.

Colonial meeting houses remain places of reverence in small towns throughout New England.

It is not surprising that eradicating town meetings, and restricting the right to free assembly, were key elements in Britain’s suppression of America’s Independence movement in the early 1770s.

Lord North, the British Prime Minister (1770-1790), instituted harsh measures to suppress dissent and disrupt the culture of self-government, which he viewed as the root cause of the chaos. On May 2, 1774, North declared Massachusetts was “in a distempered state of disturbance and opposition to the laws of the mother country.”

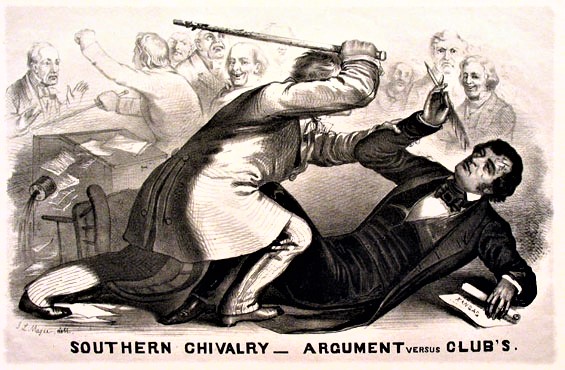

On May 20, 1774, the British Parliament passed the Massachusetts Government Act, which nullified the Massachusetts Charter of 1691. It abolished local town meetings because, “a great abuse has been made of the power of calling them, and the inhabitants have, contrary to the design of their institution, been used to treat upon matters of the most general concerns, and to pass dangerous and unwarrantable resolves.” Ongoing local meetings were replaced by annual meetings only called with the Colonial Governor’s permission, or not at all.

A series of five punitive acts were passed by Parliament intended to restrict public discourse and punish opponents. It was England’s hope the “Intolerable Acts” would intimidate rebellious Colonists into submission. The “Acts” ignited a firestorm of outrage throughout Colonial America. More importantly, it generated a unity of purpose and inspired a willingness for collective action among leaders in the previously fragmented American colonies.

In a bold “illegal” act to assert its right to free assembly, the First Continental Congress met in the Carpenters Hall in Philadelphia from September 5 to October 26, 1774. Twelve of the thirteen colonies (Georgia opted out) were represented. They issued the “Declaration of Rights and Grievances,” the first unified protest of Britain’s anti-colonial actions.

The British Crown’s assault on the right to free assembly was among the top Grievances listed in the Declaration of Independence less than two years later.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

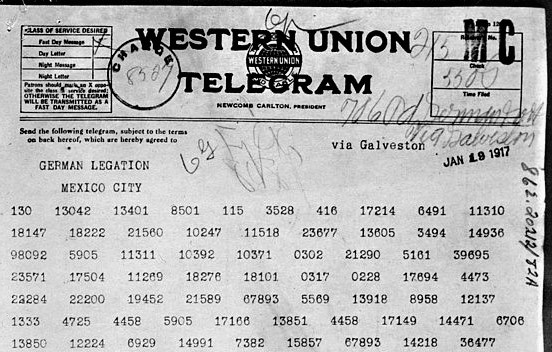

National Archives

National Archives