It’s hard to believe that this year marks thirty years since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August of 1990. In history, some events can be said to be turning points for civilization that set the world on fire, and in many ways, our international system has not been the same since the invasion of Kuwait.

Today, the Iraq that went to war against Kuwait is no more, and Saddam Hussein himself is long dead, but the battles that were fought, the policies that resulted, and the history that followed is one that will haunt the world for many more years to come.

Iraq’s attempts to annex Kuwait in 1990 would bring some of the most powerful nations into collision, and would set in motion a series of events that would give rise to the Global War on Terror, the rise of ISIS, and an ongoing instability in the region that frustrates the West to this day.

To understand the beginning of this story, one must go back in time to the Iranian Revolution in 1979, where a crucial ally of the United States of America at the time – Iran – was in turmoil because of public discontent with the leadership of its shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Iran’s combination of oil resources and strategic geographic location made it highly profitable for the shah and his allies in the West over the years, and a relationship emerged where Iran’s government, flush with oil money, kept America’s defense establishment in business.

For years, the shah had been permitted to purchase nearly any American weapons system he pleased, no matter how advanced or powerful it may be, and Congress was only all too pleased to give it to him.

The Vietnam War had broken the U.S. military and hollowed out the resources of the armed services, but the defense industry needed large contracts if was to continue to support America.

Few people realize that Iran, under the Shah, was one of the most important client states in the immediate post-Vietnam era, making it possible for America to maintain production lines of top-of-the-line destroyers, fighter planes, engines, missiles, and many other vital elements of the Cold War’s arms race against the Soviet Union. As an example, the Grumman F-14A Tomcat, America’s premier naval interceptor of 1986 “Top Gun” fame, would never have been produced in the first place if it were not for the commitment of the Iranians as a partner nation in the first batch of planes.

When the Iranian Revolution occurred, an embarrassing ulcer to American interests emerged in Western Asia, as one of the most important gravity centers of geopolitical power had slipped out of U.S. control. Iran, led by an ultra-nationalistic religious revolutionary government, and armed with what was at the time some of the most powerful weapons in the world, had gone overnight from trusted partner to sworn enemy.

Historically, U.S. policymakers typically prefer to contain and buffer enemies rather than directly opposing them. Iraq, which had also gone through a regime change in July of 1979 with the rise of Saddam Hussein in a bloody Baath Party purge, was an rival to Iran, making it a prime candidate to be America’s new ally in the Middle East.

The First Persian Gulf War: A Prelude

Hussein, a brutal, transactional-minded leader who rose to power through a combination of violence and political intrigue, was one to always exploit opportunities. Recognizing Iran’s potential to overshadow a region he himself deemed himself alone worthy to dominate, Hussein used the historical disagreement over ownership of the strategic, yet narrow Shatt al-Arab waterway that divided Iran from Iraq to start a war on September 22, 1980.

Iraq, flush with over $33 billion in oil profits, had become formidably armed with a modern military that was supplied by numerous Western European states and, bizarrely, even the Soviet Union as well. Hussein, like Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler, had a fascination for superweapons and sought to amass a high-tech military force that could not only crush Iran, but potentially take over the entire Middle East.

In Hussein’s bizarre arsenal would eventually include everything from modified Soviet ballistic missiles (the “al-Hussein”) to Dassault Falcon 50 corporate jets modified to carry anti-ship missiles, a nuclear weapons program at Osirak, and even work on a supergun capable of firing telephone booth-sized projectiles into orbit nicknamed Project Babylon.

Assured of a quick campaign against Iran and tacitly supported by the United States, Hussein saw anything but a decisive victory, and spent almost a decade in a costly war of attrition with Iran. Hussein, who constantly executed his own military officers for making tactical withdrawals or failing in combat, denied his military the ability to learn from defeats and handicapped his army by his own micromanagement.

Iraq’s Pokémon-like “gotta catch ‘em all” model of military procurement during the war even briefly put it at odds with the United States on May 17, 1987, when one of its heavily armed Falcon 50 executive jets, disguised on radar as a Mirage F1EQ fighter, accidentally launched a French-acquired Exocet missile against a U.S. Navy frigate, the USS Stark. President Ronald Reagan, though privately horrified at the loss of American sailors, still considered Iraq a necessary counterweight to Iran, and used the Stark incident to increase political pressure on Iran.

While Iraq had begun its war against Iran in the black, years of excessive military spending, meaningless battles, and rampant destruction of the Iraqi army had taken its toll. Hussein’s war had put the country in over $37 billion dollars in debt, much of which had been owed to neighboring Kuwait.

Faced with a strained economy, tens of thousands of soldiers returning wounded from the war, and a military that was virtually on the brink of deposing Saddam Hussein just as he had deposed his predecessor Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr in 1979, Iraq had no choice but to end its war against Iran.

Both Iran and Iraq would ultimately submit to a UN brokered ceasefire, but ironically, what would be one of the decisive elements in bringing the first Persian Gulf war to a close would not be the militaries of either country, but the U.S. military, when it launched a crippling air and naval attack against Iranian forces on April 18, 1988.

Iran, which had mined important sailing routes of the Persian Gulf as part of its area denial strategy during the war, succeeded on April 14, 1988 in striking the USS Samuel B. Roberts, an American frigate deployed to the region to protect shipping.

In response, the U.S. military retaliated with Operation: Praying Mantis which hit Iranian oil platforms (which had since been reconfigured as offensive gun platforms), naval vessels, and other military targets. The battle, which was so overwhelming in its scope that it actually was and remains to this day as the largest carrier and surface ship battle since World War II, resulted in the destruction of most of Iran’s navy and was a major contributing factor in de-fanging Iran for the next decade to come.

Kuwait and Oil

Saddam Hussein, claiming victory over Iran amidst the UN ceasefire, and now faced with a new U.S. president, George H.W. Bush in 1989, felt that the time was right to consolidate his power and pull his country back from collapse. In Hussein’s mind, he had been the “savior” of the Arab and Gulf States, who had protected them during the Persian Gulf war against the encroachment of Iranian influence. As such, he sought from Kuwait a forgiveness of debts incurred in the war with Iran, but would find no such sympathy. The 1990s were just around the corner, and Kuwait had ambitions of its own to grow in the new decade as a leading economic powerhouse.

Frustrated and outraged by what he perceived was a snub, Hussein reached into his playbook of once more leveraging territorial disputes for political gain and accused Kuwait of stealing Iraqi oil by means of horizontal slant drilling into the Rumaila oil fields of southern Iraq.

Kuwait found itself in an unenviable situation neighboring the heavily armed Iraq, and as talks over debt and oil continued, the mighty Iraqi Republican Guard appeared to be gearing up for war. Most political observers at the time, including many Arab leaders, felt that Hussein was merely posturing and that it was a grand bluff to maintain his image as a strong leader. For Hussein to invade a neighboring Arab ally was unthinkable at the time, especially given Kuwait’s position as an oil producer.

On July 25, 1990, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met with President Saddam Hussein and his deputy, Tariq Aziz on the topic of Kuwait. Infamously, Glaspie is said to have told the two, “We have no opinion on your Arab/Arab conflicts, such as your dispute with Kuwait. Secretary Baker has directed me to emphasize the instruction, first given to Iraq in the 1960s, that the Kuwait issue is not associated with America.”

While the George H.W. Bush administration’s intentions were obviously aimed at taking no side in a regional territorial dispute, Hussein, whose personality was direct and confrontational, likely interpreted the Glaspie meeting as America backing down.

In the Iraqi leader’s eyes, one always takes the initiative and always shows an enemy their dominance. For a powerful country such as the United States to tell Hussein that it had “no opinion” on Arab/Arab conflict, this was most likely a sign of permission or even weakness that the Iraqi leader felt he had to exploit.

America, still reeling from the shadow of the Vietnam War failure and the disastrous Navy SEAL incident in Operation: Just Cause in Panama, may have appeared in that moment to Hussein as a paper tiger that could be out-maneuvered or deterred by aggressive action. Whatever the case was, Iraq stunned the world when just days later on August 2, 1990 it invaded Kuwait.

The Invasion of Kuwait

American military forces and intelligence agencies had been closely monitoring the buildup of Iraqi forces for what appeared like an invasion of Kuwait, but it was still believed right up to the moment of the attack that perhaps Saddam Hussein was only bluffing. The United States Central Command had set WATCHCON 1 – or Watch Condition One – the highest state of non-nuclear alertness in the region just prior to Iraq’s attack, and was regularly employing satellites, reconnaissance aircraft, and electronic surveillance platforms to observe the Iraqi Army.

Nevertheless, if there is one mantra that perfectly encapsulates the posture of the United States and European powers from the beginnings of the 20th century to the present, it is “Western countries too slow to act.” As is often the result with aggressive nations that challenge the international order, Iraq plowed into Kuwait and savaged the local population.

While America and her allies have always had the best technologies, the best weapons, and the best early warning systems or sensors, these historically for more than a century have been rendered useless because they often provide information that is not actionably employed to stop an attack or threat. Such was the case with Iraq, where all of the warning signs were present that an attack was imminent, but no action was taken to stop them.

Kuwait’s military courageously fought Iraq’s invading army, and even notably fought air battles with their American-made A-4 Skyhawks, some of them launching from highways after their air bases were destroyed. But the Iraqi army, full of troops who had fought against Iran and equipped with the fourth largest military in the world at that time, was simply too powerful to overcome. 140,000 Iraqi troops flooded into Kuwait and seized one of the richest oil producing nations in the region.

As Hussein’s military overran Kuwait, sealed its borders, and began plundering the country and ravaging its civilian population, the worry of the United States immediately shifted from Kuwait to Saudi Arabia, for fear that the kingdom might be next. On August 7, 1990, President Bush commenced “Operation: Desert Shield,” a military operation to defend Saudi Arabia and prevent any further advance of the Iraqi army.

At the time that Operation: Desert Shield commenced, I was living in Hampton Roads, Virginia and my father was a lieutenant colonel assigned to Tactical Air Command headquarters at the nearby Langley Air Force Base, and 48 F-15 Eagle fighter planes from that base immediately deployed to the Middle East in support of that operation. In the days that followed, our base became a flurry of activity and I remember seeing a huge buildup of combat aircraft from all around the United States forming at Langley.

President Bush, who himself had been a fighter pilot and U.S. Navy officer who fought in World War II, was all too familiar with what could happen when a megalomaniacal dictator started invading their neighbors. Whatever congeniality of convenience existed between the U.S. and Iraq to oppose Iran was now a thing of the past in the wake of the occupation of Kuwait.

Having fought against both the Nazis and Imperial Japanese in WWII, Bush saw many similarities of Adolf Hitler in Saddam Hussein, and immediately began comparing the Iraqi leader and his government to the Nazis in numerous speeches and public appearances as debates raged over what the U.S. should do regarding Kuwait.

As retired, former members of previous presidential administrations urged caution and called for long-term sanctions on Iraq rather than a kinetic military response, the American public, still captivated by the Vietnam experience, largely felt that the matter in Kuwait was not a concern that should involve military forces. Protests began to break out across America with crowds shouting “Hell no, we won’t go to war for Texaco” and others singing traditional protest songs of peace like “We Shall Overcome.”

Bush, persistent in his beliefs that Iraq’s actions were intolerable, made every effort to keep taking the moral case for action to the American public in spite of these pushbacks. As a leader seasoned by the horrors of war and combat, Bush must have known, as Henry Kissinger once said, that leadership is not about popularity polls, but about “an understanding of historical cycles and courage.”

On September 11, 1990, before a joint session of Congress, Bush gave a fiery address that to this day still stands as one of the most impressive presidential addresses in history.

“Vital issues of principle are at stake. Saddam Hussein is literally trying to wipe a country off the face of the Earth. We do not exaggerate,” President Bush would say before Congress. “Nor do we exaggerate when we say Saddam Hussein will fail. Vital economic interests are at risk as well. Iraq itself controls some 10 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves. Iraq, plus Kuwait, controls twice that. An Iraq permitted to swallow Kuwait would have the economic and military power, as well as the arrogance, to intimidate and coerce its neighbors, neighbors who control the lion’s share of the world’s remaining oil reserves. We cannot permit a resource so vital to be dominated by one so ruthless, and we won’t!”

Members of Congress erupted in roaring applause at Bush’s words, and he issued a stern warning to Saddam Hussein: “Iraq will not be permitted to annex Kuwait. And that’s not a threat, that’s not a boast, that’s just the way it’s going to be.”

Ejecting Saddam from Kuwait

As America prepared for action, in Saudi Arabia, another man would also be making promises to defeat Saddam Hussein and his military. Osama bin Laden, who had participated in the earlier war in Afghanistan as part of the Mujahideen that resisted the Soviet occupation, now offered his services to Saudi Arabia, pledging to use a jihad to force Iraq out of Kuwait in the same way that he had forced the Soviets out of Afghanistan. The Saudis, however, would hear none of it; having already received the protection of the United States and its powerful allies, bin Laden, seen as a useless bit player on the world stage, was brushed aside.

Herein the seeds for a future conflict would be sown, as not only did bin Laden take offense to being rejected by the Saudi government, but the presence of American military forces on holy Saudi soil was seen as blasphemous to him and a morally corrupting influence on the Saudi people.

In fact, the presence of female U.S. Air Force personnel in Saudi Arabia seen without traditional cover or driving around in vehicles, caused many Saudi women to begin petitioning their government – and even in some instances, committing acts of civil disobedience – for more rights. This caused even more outrage among a number of fundamentalist groups in Saudi Arabia, and lent additional support, albeit covert in some instances, to bin Laden and other jihadist leaders.

Despite these cultural tensions boiling beneath the surface, President Bush successfully persuaded not only his own Congress but the United Nations as well to empower the formation of a global coalition of 35 nations to eject Iraqi occupying forces from Kuwait and to protect Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf from further aggression.

On November 29, 1990, the die was cast when the United Nations passed Resolution 678, authorizing “Member States co-operating with the Government of Kuwait, unless Iraq on or before 15 January 1991 [withdraws from Kuwait] … to use all necessary means … to restore international peace and security in the area.”

Subsequently, on January 15, 1991, President Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein to leave Kuwait. Hussein ignored the threat, believing that America was weak, and its public easily susceptible to knee-jerk reactions at the sight of losing soldiers from its prior experience in Vietnam. Hussein believed that he could not only cause the American people to back down, but that he could unravel Arab support for the UN coalition by enticing Israel to attack Iraq. As such, he persisted in occupying Kuwait and boasted that a “Mother of all Battles” was to commence, in which Iraq would emerge victorious.

History, however, shows us that this was not the case, and days later on the evening of January 16, 1991, Operation: Desert Shield became Operation: Desert Storm, when a massive aerial bombardment and air superiority campaign commenced against Iraqi forces. Unlike prior wars which combined a ground invasion with supporting air forces, the start of Desert Storm was a bombing campaign that consisted of heavy attacks by aircraft and naval-launched cruise missiles against Iraq.

The operational name “Desert Storm” may have in part been influenced by a war plan developed months earlier by Air Force planner, Colonel John A. Warden who conceived an attack strategy named “Instant Thunder” which used conventional, non-nuclear airpower in a precise manner to topple Iraqi defenses.

A number of elements from Warden’s top secret plan were integrated into the opening shots of Desert Storm’s air campaign, as U.S. and coalition aircraft knocked out Iraqi radars, missile sites, command headquarters, power stations, and other key targets in just the first night alone.

Unlike the Vietnam air campaigns which were largely political and gradual escalations of force, the Air Force, having suffered heavy losses in Vietnam, wanted as General Chuck Horner would later explain, “instant” and “maximum” escalation so that their enemies could not have time to react or rearm.

This was precisely what happened, such to the point that the massive Iraqi air force would be either annihilated by bombs on the ground, shot down by coalition combat air patrols, or forced to flee into neighboring Iran.

A number of radical operations and new weapons were employed in the air campaign of Desert Storm. For one, the U.S. Air Force had secretly converted a number of nuclear AGM-86 Air Launched Cruise Missiles (ALCMs) into conventional, high explosive precision guided missiles and equipped them on 57 B-52 bombers for a January 17 night raid called Operation: Senior Surprise.

Known internally and informally to the B-52 pilots as “Operation: Secret Squirrel,” the cruise missiles knocked out numerous Iraqi defenses and opened the door for more coalition aircraft to surge against Saddam Hussein’s military.

The Navy also employed covert strikes against Iraq, also firing BGM-109 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs) that had also been converted to carry high explosive (non-nuclear) warheads. Because the early BGM-109s were guided and aimed by a primitive digital scene matching area correlator (DSMAC) that took digital photos of the ground below and compared it with pre-programmed topography in its terrain computer, the flat deserts of Iraq were thought to be problematic in employing cruise missiles, so the Navy came up with a highly controversial solution: secretly fire cruise missiles into Iran – a violation of Iranian airspace and international law – then turn them towards the mountain ranges as aiming points, and fly them into Iraq.

The plan worked, however, and the Navy would ultimately rain down on Iraq some 288 TLAMs that destroyed hardened hangars, runways, parked aircraft, command buildings, and scores of other targets in highly accurate strikes.

Part of the air war came home personally to me when a U.S. Air Force B-52, serial number 58-0248, participated in a night time raid over Iraq when it was accidentally fired upon by a friendly F-4G “Wild Weasel” that mistook the lumbering bomber’s AN/ASG-21 radar-guided tail gun as an Iraqi air defense platform. The Wild Weasel fired an AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) at the B-52 that hit and exploded in its tail, but still left the aircraft in flyable condition.

At the time, my family had moved to Andersen AFB in Guam, and 58-0248 made for Guam to land for repairs. When the B-52 arrived, it was parked in a cavernous hangar and crews immediately began patching up the aircraft. My father, always wanting to ensure that I learned something about the real world so I could get an appreciation for America, brought me to the hangar to see the stricken B-52, which was affectionately given the nickname “In HARM’s Way.”

I never forgot that moment, and it caused me to realize that the war was more than just some news broadcast we watched on TV, and that war had real consequences for not only those who fought in it, but people back home as well. I remember feeling an intense surge of pride as I saw that B-52 parked in the hangar, and I felt that I was witnessing history in action.

Ultimately, the air war against Saddam Hussein’s military would go on for a brutal six weeks, leaving many of his troops shell-shocked, demoralized, and eager to surrender. In fighting Iran for a decade, the Iraqi army had never known the kind of destructive scale or deadly precision that coalition forces were able to bring to bear against them.

Once the ground campaign commenced against Iraqi forces on February 24, 1991, that portion of Operation: Desert Storm only lasted a mere 100 hours before a cease-fire would be called, not because Saddam Hussein had pleaded for survival, but because back in Washington, D.C., national leaders watching the war on CNN began to see a level of carnage that they were not prepared for.

Gen. Colin Powell, seeing that most of the coalition’s UN objectives had been essentially achieved, personally lobbied for the campaign to wrap up, feeling that further destruction of Iraq would be “unchivalrous” and fearing the loss of any more Iraqi or American lives. It was also feared that if America had actually tried to make a play for regime change in Iraq in 1991, that the Army would be left holding the bag in securing and rebuilding the country, something that not only would be costly, but might turn the Arab coalition against America. On February 28, 1991, the U.S. officially declared a cease-fire.

The Aftermath

Operation: Desert Storm successfully accomplished the UN objectives that were established for the coalition forces and it liberated Kuwait. But a number of side effects of the war would follow that would haunt America and the rest of the world for decades to come.

First, Saddam Hussein remained in power. As a result, the U.S. military would remain in the region for years as a defensive contingent, not only continuing to inflame existing cultural tensions in Saudi Arabia, but also becoming a target for jihadist terrorist attacks, including the Khobar Towers bombing on June 25, 1996 and the USS Cole bombing on October 12, 2000.

Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda terrorist group would ultimately change the modern world as we knew it when his men hijacked commercial airliners and flew them into the Pentagon and World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. It should not be lost on historical observers that 15 of the 19 hijackers that day were Saudi citizens, a strategic attempt by bin Laden to drive a wedge between the United States and Saudi Arabia to get American military forces out of the country.

9/11 would also provide an opportunity for George H.W. Bush’s son, President George W. Bush, to attempt to take down Saddam Hussein. Many of the new Bush Administration members were veterans of the previous one during Desert Storm, and felt that the elder Bush’s decision not to “take out” the Iraqi dictator was a mistake. And while the 2003 campaign against Iraq was indeed successful in taking down the Baathist-party rule in Iraq and changing the regime, it allowed many disaffected former Iraqi officers and jihadists to rise up against the West, which ultimately led to the rise of ISIS in the region.

It is my hope that the next generation of college and high school students who read this essay and reflect on world affairs will understand that history is often complex and that every action taken leaves ripples in our collective destinies. A Holocaust survivor once told me, “There are times when the world goes crazy, and catches on fire. Desert Storm was one such time when the world caught on fire.”

What can we learn from the invasion of Kuwait, and what lessons can we take forward into our future? Let us remember always that allies are not always friends; victories are never permanent; and sometimes even seemingly unrelated personalities and forces can lead to world-changing events.

Our young people, especially those who wish to enter into national service, must study history and seek to possess, as the Bible says in the book of Revelation 17:9 in the Amplified Bible translation, “a mind to consider, that is packed with wisdom and intelligence … a particular mode of thinking and judging of thoughts, feelings, and purposes.”

Indeed, sometimes the world truly goes crazy and catches on fire, and some may say that 2020 is such a time. Let us study the past now, and prepare for the future!

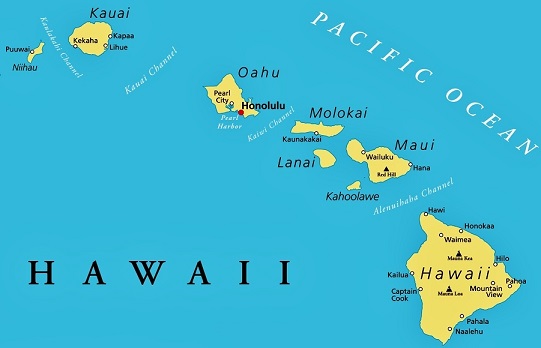

Dr. Danny de Gracia, Th.D., D.Min., is a political scientist, theologist, and former committee clerk to the Hawaii State House of Representatives. He is an internationally acclaimed author and novelist who has been featured worldwide in the Washington Times, New York Times, USA Today, BBC News, Honolulu Civil Beat, and more. He is the author of the novel American Kiss: A Collection of Short Stories.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Airman 1st Class Victor J. Caputo - US Air Force

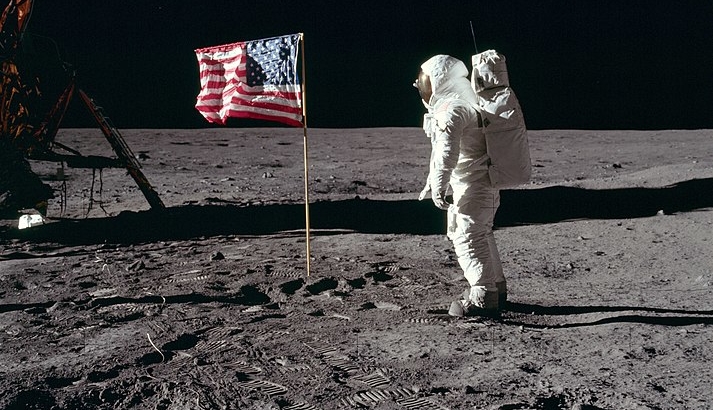

Airman 1st Class Victor J. Caputo - US Air Force NASA

NASA