December 6, 1865: The Thirteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is Ratified, Abolishing Slavery

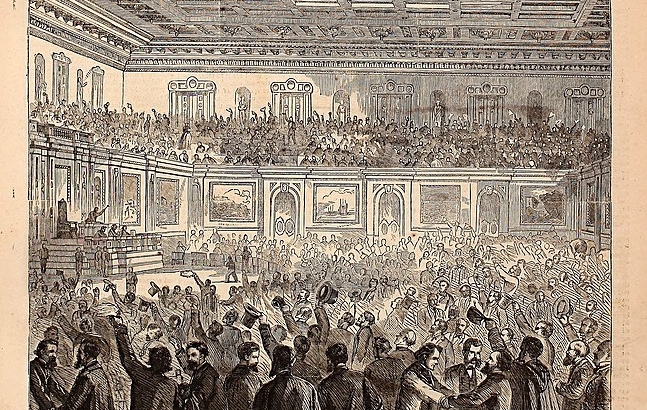

Notwithstanding the controversy over the causes of the U.S. Civil War, we do know that one of the outcomes was ending slavery through the Thirteenth Amendment. Congress passed the proposed Thirteenth Amendment on January 31, 1865 and it was subsequently ratified on December 6, 1865 by three-fourths of the state legislatures. Upon its ratification, the Thirteenth Amendment made slavery unconstitutional.

Unlike amendments before it, this amendment deserves special consideration due to the unconventional proposal and ratification process.

The proposed amendment passed the Senate on April 8, 1864 and the House on January 31, 1865 with President Abraham Lincoln approving the Joint Resolution to submit the proposed amendment to the states on February 1, 1865. But, it was not until April 9, 1865 that the U.S. Civil War officially ended on the steps of the Appomattox Courthouse when Robert E. Lee surrendered the Confederate Army to Ulysses S. Grant. This means that all congressional action up to this point took place without the consent of any state in the Confederacy taking part as those states were not represented in congress.

However, once the war ended, the success of the amendment required that some of the former Confederate states ratify the amendment in order to meet the constitutionally mandated minimum proportion of states. Article V of the Constitution requires three-fourths of state legislatures to ratify a proposed amendment before it can become part of the Constitution. There were only twenty-five Union and border states which meant at least two states from the eleven that comprised the Confederacy had to ratify.

The effort to get states to ratify was led by Andrew Johnson who assumed the presidency after Lincoln was assassinated on April 15, 1865. There was a total of thirty-six states which meant at least twenty-seven of the state legislatures had to ratify. It was not guaranteed that all the states that remained in the Union would ratify. For instance, New Jersey, Delaware and Kentucky all initially rejected the amendment.

This is where things get complicated. When Johnson assumed the presidency in April, he ordered his generals to summon new conventions in the Southern states that would be forced to revise constitutions and elect new state legislators before being admitted back into the Union. This was essentially reform through military injunction thus casting doubt on the sovereignty of the states and the free will of the people.

Further complicating the issue of ratification was the Thirty-ninth Congress which refused the inclusion of all the Southern states except Tennessee. So, while the Congress did not recognize the former Confederate states as states—except Tennessee—all the states were considered legal for purposes of ratification as determined by Secretary of State William Seward. Thus, we are presented with a constitutional predicament in which an amendment is ratified by states recognized by the executive branch but not by the legislative branch.

No resolution was formerly adopted, nor reconciliation made, that could bring clarity to this constitutional crisis. Reconstruction continued, and the Thirteenth Amendment was added to the Constitution along with the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments—collectively known as the Reconstruction Amendments.

The ratification of the Reconstruction Amendments is most aptly characterized as a Second Founding. How the Amendments were ratified occurred outside any reasonable interpretation of Article V or republican principles of representation. Imagine the following scenario. Armed guards move into 51% of American voters’ homes and force them to vote for Candidate A in the next presidential election. If the homeowners do not agree, the armed guards stay. If homeowners agree, and vote for Candidate A, the armed guards leave. This is what occurred during Reconstruction in the South as a state’s inclusion in Congress, and the removal of Union troops, was predicated upon that state’s acquiescence to the demands of the Union which included ratifying the Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments.

Because the amendments were passed in an extra-constitutional manner, we cannot say that they were a continuation of what was laid out in Philadelphia several decades before. This creates an ethical dilemma for historians and legal scholars to consider. Do the ends justify the means or should the letter of the law be subservient to the higher good? To state it more simply: Is ending slavery worth violating the Constitution? Or, should have slavery remained legal until an amendment could be ratified in a manner consistent with Article V and generally accepted principles of representation?

These questions are meant to be hard and they will not be resolved here. What I do propose is that in 1865 the United States decided that the pursuit of the higher good justified a violation of accepted procedures and those who accept the validity of the Reconstruction Amendments today must, at least tacitly, endorse the same.

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA, currently works in higher education administration and has taught American politics, Constitutional Law, and political theory for more than a decade at the university level. He is the author of five books and more than a dozen peer-reviewed articles. His most recent book is The Federalist Papers: A Reader’s Guide. Kyle can be contacted at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!