Conclusion: American Republicanism as a Way of Life

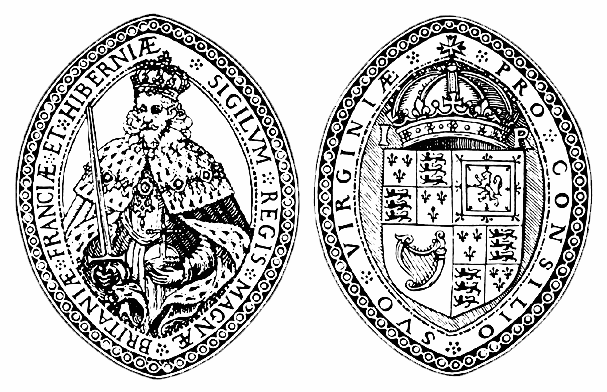

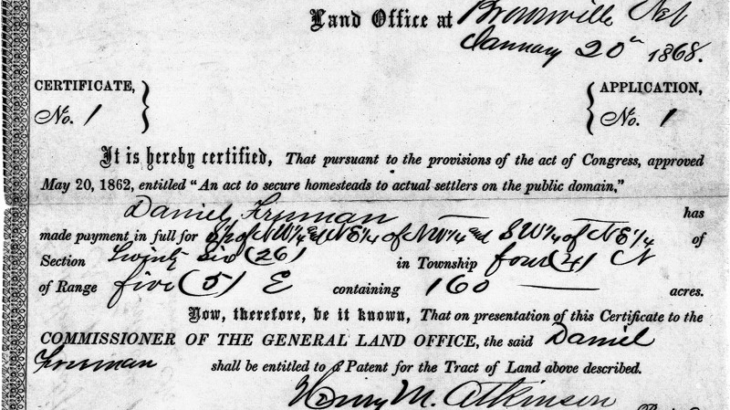

90 in 90 2020, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, William Morrisey, Ph.D. Conclusion: American Republicanism as a Way of Life – Guest Essayist: Will Morrisey, 10. Dates in American History, 2020 - Dates in American History, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, William Morrisey PhDTo secure the unalienable natural rights of the American people, the American Founders designed a republican regime. Republics had existed before: ancient Rome, modern Switzerland and Venice. By 1776, Great Britain itself could be described as a republic, with a strong legislature counterbalancing a strong monarchy—even if the rule of that legislature and that monarchy over the overseas colonies of the British Empire could hardly be considered republican. But the republicanism instituted after the War of Independence, especially as framed at the Philadelphia Convention in 1787, featured a combination of elements never seen before, and seldom thereafter.

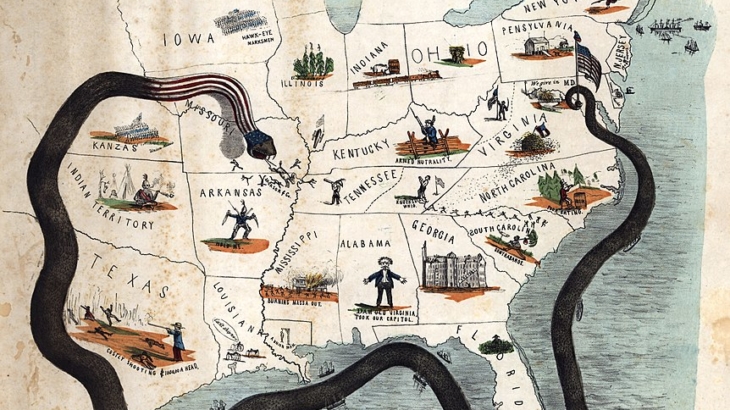

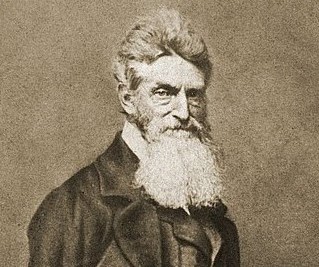

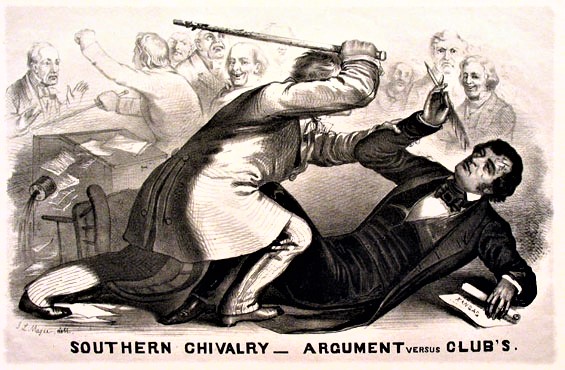

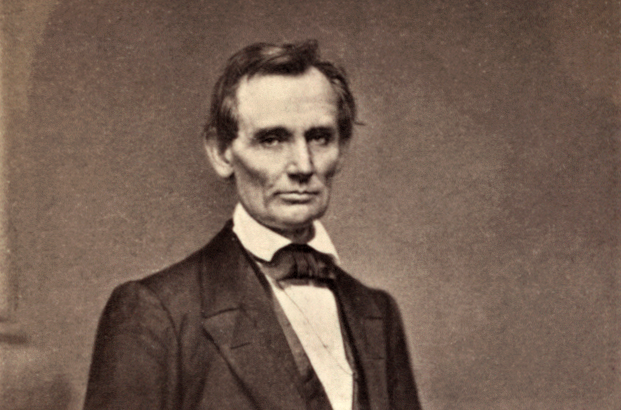

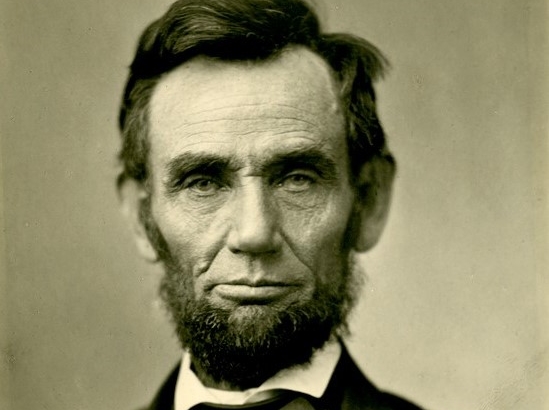

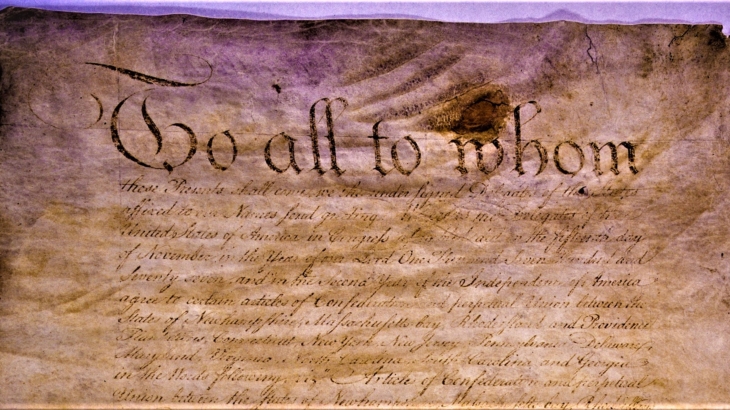

The American definition of republicanism was itself unique. ‘Republic’ or res publica means simply, ‘public thing’—a decidedly vague notion that might apply to any regime other than a monarchy. In the tenth Federalist, James Madison defined republicanism as representative government, that is, by a specific way of constructing the country’s ruling institutions. The Founders gave republicanism a recognizable form beyond ‘not-monarchy.’ From the design of the Virginia House of Burgesses to the Articles of Confederation and finally to the Constitution itself, representation provided Americans with real exercise of self-rule, while at the same time avoiding the turbulence and folly of pure democracies, which had so disgraced themselves in ancient Greece that popular sovereignty itself had been dismissed by political thinkers ever since. Later on, Abraham Lincoln’s Lyceum Address shows how republicanism must defend the rule of law against mob violence; even the naming of Lincoln’s party as the Republican Party was intended to contrast it with the rule of slave-holding plantation oligarchs in the South.

The American republic had six additional characteristics, all of them clearly registered in this 90-Day Study. America was a natural-rights republic, limiting the legitimate exercise of popular rule to actions respecting the unalienable rights of its citizens; it was a democratic republic, with no formal ruling class of titled lords and ladies or hereditary monarchs; it was an extended republic, big enough to defend itself against the formidable empires that threatened it; it was a commercial republic, encouraging prosperity and innovation; it was a federal republic, leaving substantial political powers in the hands of state and local representatives; and it was a compound republic, dividing the powers of the national government into three branches, each with the means of defending itself against encroachments by the others.

Students of the American republic could consider each essay in this series as a reflection on one or more of these features of the American regime as designed by the Founders, or, in some cases, as deviations from that regime. Careful study of what the Declaration of Independence calls “the course of events” in America shows how profound and pervasive American republicanism has been, how it has shaped our lives throughout our history, and continues to do so today.

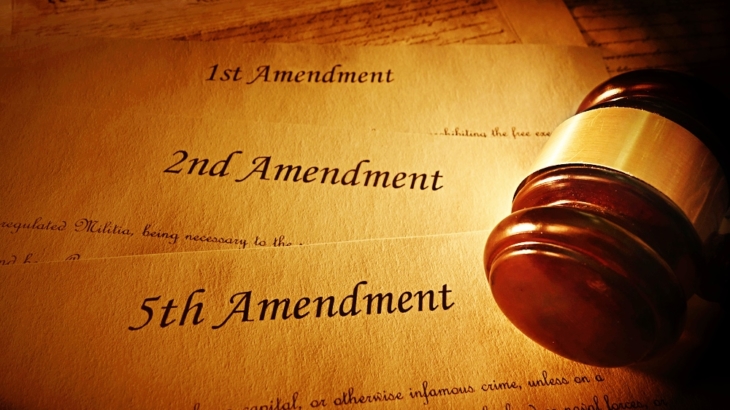

A Natural-Rights Republic

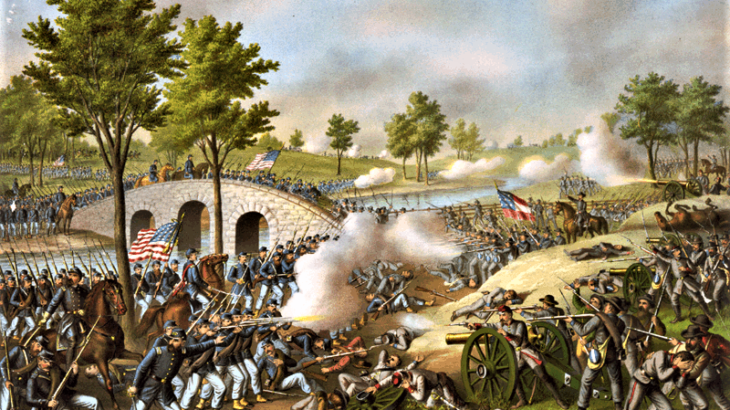

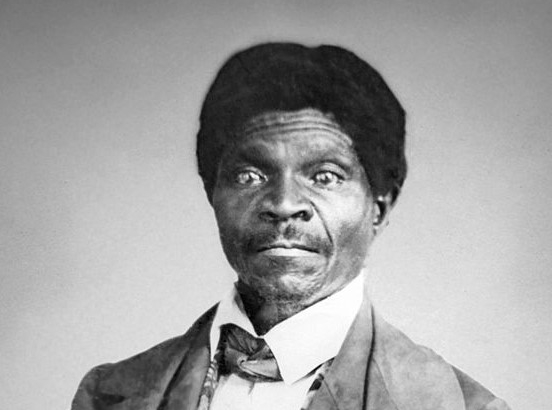

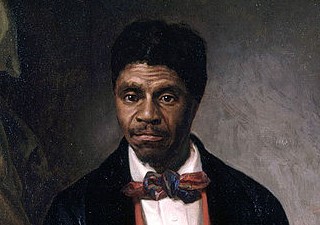

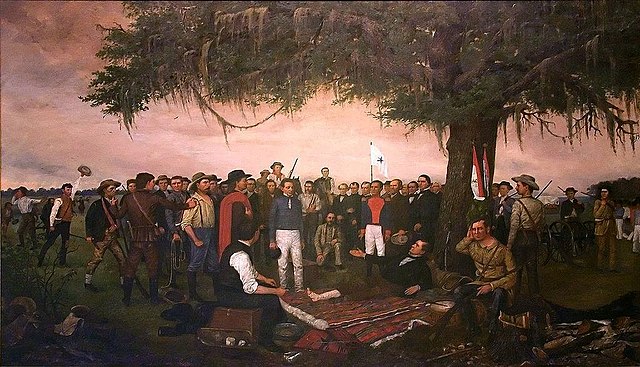

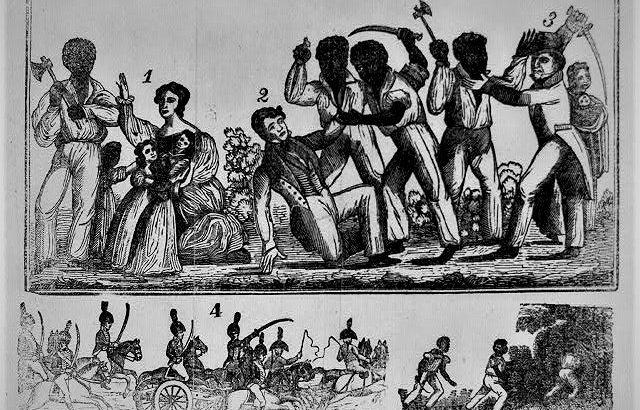

The Jamestown colony’s charter was written in part by the great English authority on the common law, Sir Edward Coke. Common law was an amalgam of natural law and English custom. The Massachusetts Bay Colony, founded shortly thereafter, was an attempt to establish the natural right of religious liberty. And of course the Declaration of Independence rests squarely on the foundation of the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God as the foundation of unalienable natural rights, several of which were given formal status in the Constitution’s Bill of Rights. As the articles on Nat Turner’s slave rebellion in 1831, the Dred Scott case in 1857, the Civil Rights amendments of the 1860s, and the attempt at replacing plantation oligarchy with republican regimes in the states after the Civil War all show, natural rights have been the pivot of struggles over the character of America. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the early civil rights leaders invoked the Declaration and natural rights to argue for civic equality, a century after the civil war. As a natural-rights republic, America rejects in principle race, class, and gender as bars to the protection of the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In practice, Americans have often failed to live up to their principles—as human beings are wont to do—but the principles remain as their standard of right conduct.

A Democratic Republic

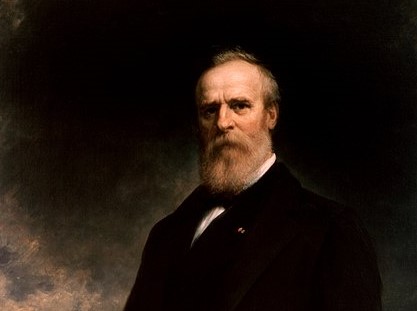

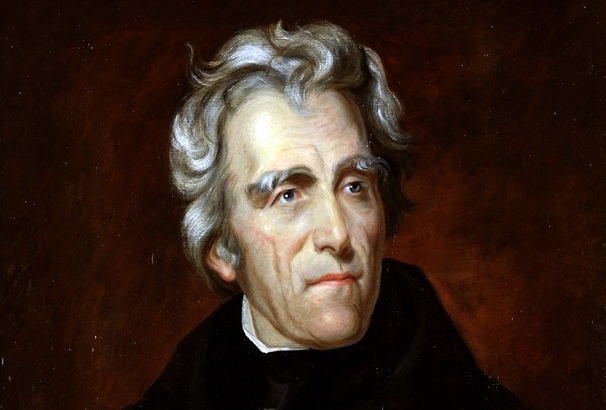

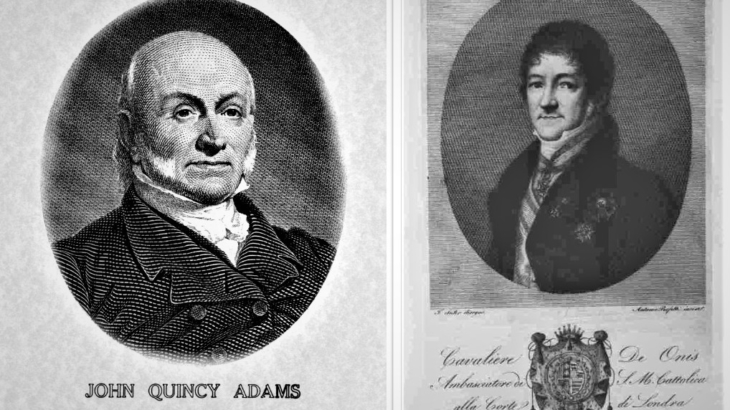

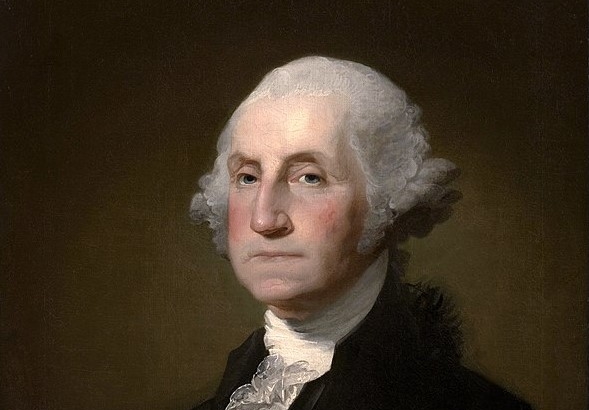

The Constitution itself begins with the phrase “We the People,” and the reason constitutional law governs all statutory laws is that the sovereign people ratified that Constitution. George Washington was elected as America’s first president, but he astonished the world by stepping down eight years later; he had no ambition to become another George III, or a Napoleon. The Democratic Party which began to be formed by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison when they went into opposition against the Adams administration named itself for this feature of the American regime. The Seventeenth Amendment to the Constitution, providing for popular election of U. S. Senators, the Nineteenth Amendment, guaranteeing voting rights for women, and the major civil rights laws of the 1960s all express the democratic theme in American public life.

An Extended Republic

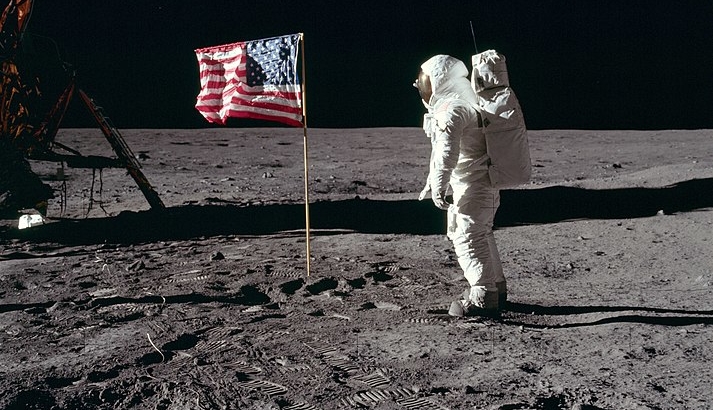

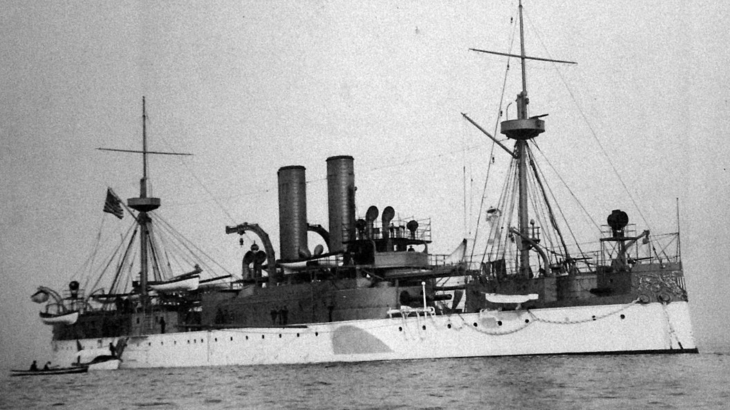

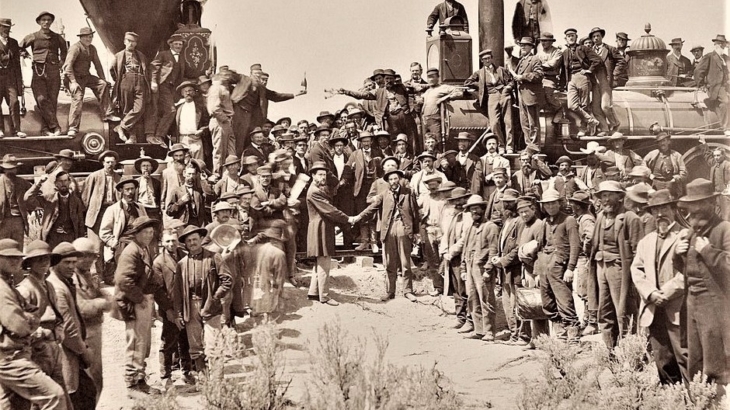

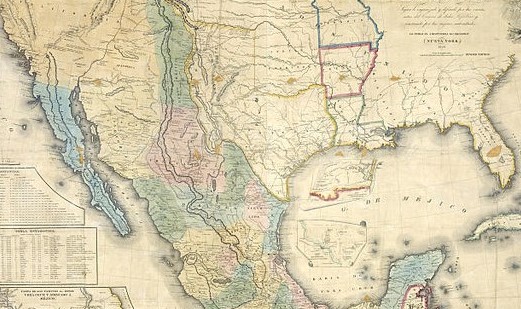

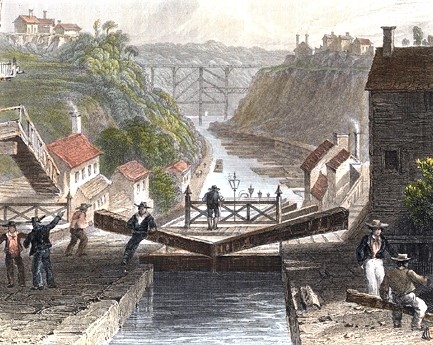

Unlike the ancient democracies, which could only rule small territories, American republicanism gave citizens the chance of ruling themselves in a territory large enough to defend itself against the powerful states and empires that had arisen in modern times. All of this was contingent, however, on Jefferson’s idea that this extended republic would be an “empire of liberty,” by which he meant that new territories would be eligible to join the Union on an equal footing with the original thirteen states. Further, every state was to have a republican regime, as stipulated in the Constitution’s Article IV, section iv. In this series of Constituting America essays, the extension of the extended republic is very well documented, from the 1803 Louisiana Purchase and the Lewis and Clark expedition to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the Mexican War of 1848, to the purchase of Alaska and the Transcontinental Railroad of the 1960s, to the Interstate Highway Act of 1956. The construction of the Panama Canal, the two world wars, and the Cold War all followed from the need to defend this large republic from foreign regime enemies and to keep the sea lanes open for American commerce.

A Commercial Republic

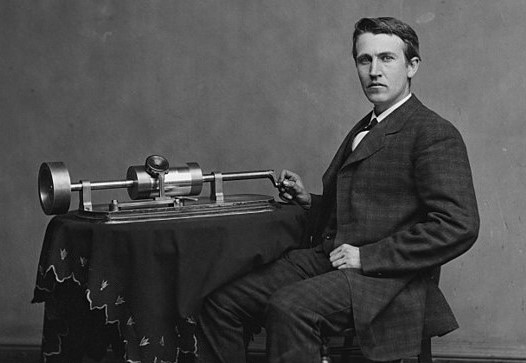

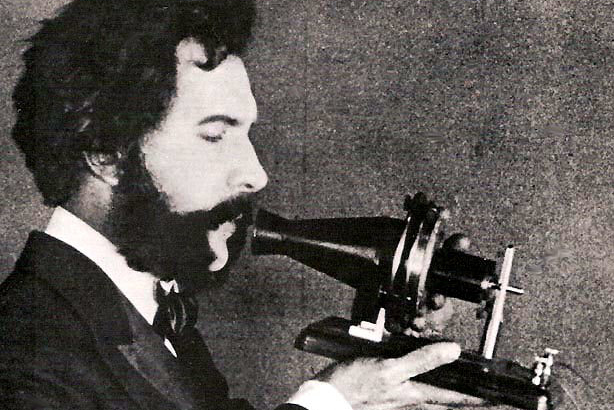

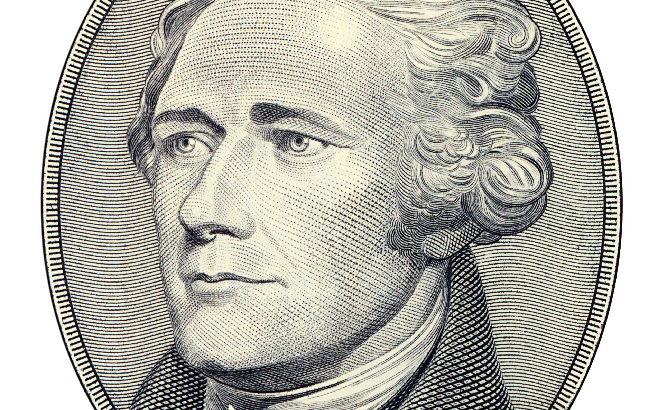

Although it has proven itself eminently capable of defending itself militarily, America was not intended to be a military republic, like ancient Rome and the First Republic of France. The Constitution prohibits interstate tariffs, making the United States a vast free-trade zone—something Europe could not achieve for another two centuries. We have seen Alexander Hamilton’s brilliant plan to retire the national debt after the Revolutionary War and the founding of the New York Stock Exchange in 1792. Above all, we have seen how the spirit of commercial enterprise leads to innovation: Eli Morse’s telegraph; Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone; Thomas Edison’s phonography and light bulb; the Wright Brothers’ flying machine; and Philo Farnworth’s television. And we have seen how commerce in a free market can go wrong if the legislation and federal policies governing it are misconceived, as they often were before, during, and sometimes after the Great Depression.

A Federal Republic

A republic might be ‘unitary’—ruled by a single, centralized government. The American Founders saw that this would lead to an overbearing national government, one that would eventually undermine republican self-government itself. They gave the federal government enumerated powers, leaving the remaining governmental powers “to the States, or the People.” The Civil War was fought over this issue, as well as slavery, the question of whether the American Union could defend itself against its internal enemies. The substantial centralization of federal government power seen in the New Deal of the 1930s, the Great Society legislation of the 1960s, and the Affordable Care Act of 2010 have renewed the question of how far such power is entitled to reach.

A Compound Republic

A simple republic would elect one branch of government to exercise all three powers: legislative, executive, and judicial. This was the way the Articles of Confederation worked. The Constitution ended that, providing instead for the separation and balance of those three powers. As the essays here have demonstrated, the compound character of the American republic has been eroded by such notions as ‘executive leadership’—a principle first enunciated by Woodrow Wilson but firmly established by Franklin Roosevelt and practiced by all of his successors—and ‘broad construction’ of the Constitution by the Supreme Court. The most dramatic struggle between the several branches of government in recent decades was the Watergate controversy, wherein Congress attempted to set limits on presidential claims of ‘executive privilege.’ Recent controversies over the use of ‘executive orders’ have reminded Americans of all political stripes that government by decree can gore anyone’s prized ox.

The classical political philosophers classified the forms of political rule, giving names to the several ‘regimes’ they saw around them. They emphasized the importance of regimes because regimes, they knew, designate who rules us, the institutions by which the rulers rule, the purposes of that rule, and finally the way of life of citizens or subjects. In choosing a republican regime on a democratic foundation, governing a large territory for commercial purposes with a carefully calibrated set of governmental powers, all intended to secure the natural rights of citizens according to the laws of Nature and of Nature’s God, the Founders set the course of human events on a new and better direction. Each generation of Americans has needed to understand the American way of life and to defend it.

Will Morrisey is Professor Emeritus of Politics at Hillsdale College, editor and publisher of Will Morrisey Reviews, an on-line book review publication.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

March 23, 2010: President Barack H. Obama Signs the Affordable Care Act

90 in 90 2020, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Joerg W. Knipprath March 23, 2010: President Barack H. Obama Signs the Affordable Care Act – Guest Essayist: Joerg Knipprath, 10. Dates in American History, 2020 - Dates in American History, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Joerg W. KnipprathOn March 23, 2010, President Barack Obama signed into law the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (“ACA”), sometimes casually referred to as “Obamacare,” a sobriquet that Obama himself embraced in 2013. The ACA covered 900 pages and hundreds of provisions. The law was so opaque and convoluted that legislators, bureaucrats, and Obama himself at times were unclear about its scope. For example, the main goal of the law was presented as providing health insurance to all Americans who previously were unable to obtain it due to, among other factors, lack of money or pre-existing health conditions. The law did increase the number of individuals covered by insurance, but stopped well short of universal coverage. Several of its unworkable or unpopular provisions were delayed by executive order. Others were subject to litigation to straighten out conflicting requirements. The ACA represented a probably not-yet-final step in the massive bureaucratization of health insurance and care over the past several decades, as health care moved from a private arrangement to a government-subsidized “right.”

The law achieved its objectives to the extent it did by expanding Medicaid eligibility to higher income levels and by significantly restructuring the “individual” policy market. In other matters, the ACA sought to control costs by further reducing Medicare reimbursements to doctors, which had the unsurprising consequence that Medicare patients found it still more difficult to get medical care, and by levying excise taxes on medical devices, drug manufacturers, health insurance providers, and high-benefit “Cadillac plans” set-up by employers. The last of these was postponed and, along with most of the other taxes, repealed in December, 2019. On the whole, existing employer plans and plans under collective-bargaining agreements were only minimally affected. Insurers had to cover defined “essential health services,” whether or not the purchaser wanted or needed those services. As a result, certain basic health plans that focused on “catastrophic events” coverage were substandard and could no longer be offered. Hence, while coverage expanded, many people also found that the new, permitted plans cost them more than their prior coverage. They also found that the reality did not match Obama’s promise, “if you like your health care plan, you can keep your health care plan.”

The ACA required insurance companies to “accept all comers.” This policy would have the predictable effect that healthy (mostly young) people would forego purchasing insurance until a condition arose that required expensive treatment. That, in turn, would devastate the insurance market. Imagine being able to buy a fire policy to cover damage that had already arisen from a fire. Such policies would not be issued. Private, non-employer, health insurance plans potentially would disappear. Some commentators opined that this was exactly the end the reformers sought, at least secretly, so as to shift to a single-payer system, in other words, to “Medicare for all.” The ACA sought to address that problem by imposing an “individual mandate.” Unless exempt from the mandate, such as illegal immigrants or 25-year-olds covered under their parents’ policy, every person must purchase insurance through their employer or individually from an insurer through one of the “exchanges.” Barring that, the person had to pay a penalty, to be collected by the IRS.

There have been numerous legal challenges to the ACA. Perhaps the most significant constitutional challenge was decided by the Supreme Court in 2012 in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius (NFIB). There, the Court addressed the constitutionality of the individual mandate under Congress’s commerce and taxing powers, and of the Medicaid expansion under Congress’s spending power. These two provisions were deemed the keys to the success of the entire project.

Before the Court could address the case’s merits, it had to rule that the petitioners had standing to bring their constitutional claim. The hurdle was the Anti-Injunction Act. That law prohibited courts from issuing an injunction against the collection of any tax, in order to prevent litigation from obstructing tax collection. Instead, a party must pay the tax and sue for a refund to test the tax’s constitutionality. The issue turned on whether the individual mandate was a tax or a penalty. Chief Justice John Roberts concluded that Congress had described this “shared responsibility payment” if one did not purchase qualified health insurance as a “penalty,” not a “tax.” Roberts noted that other parts of the ACA imposed taxes, so that Congress’s decision to apply a different label was significant. Left out of the opinion was the reason that Congress made what was initially labeled a “tax” into a “penalty” in the ACA’s final version, namely, Democrats’ sensitivity about Republican allegations that the proposed bill raised taxes on Americans.

Having confirmed the petitioners’ standing, Roberts proceeded to the substantive merits of the challenge to the ACA. The government argued that the health insurance market (and health care, more generally) was a national market in which everyone would participate, sooner or later. While this is a likely event, it is by no means a necessary one, as a person might never seek medical services. If, for whatever reason, people did not have suitable insurance, the government claimed, they might not be able to pay for those services. Because hospitals are legally obligated to provide some services regardless of the patient’s ability to pay, hospitals would pass along their uncompensated costs to insured patients, whose insurance companies in turn would charge those patients higher premiums. The ACA’s broadened insurance coverage and “guaranteed-issue” requirements, subsidized by the minimum insurance coverage requirement, would ameliorate this cost-shifting. Moreover, the related individual mandate was “necessary and proper” to deal with the potential distortion of the market that would come from younger, healthier people opting not to purchase insurance as sought by the ACA.

Of course, Congress could pass laws under the Necessary and Proper Clause only to further its other enumerated powers, hence, the need to invoke the Commerce Clause. The government relied on the long-established, but still controversial, precedent of Wickard v. Filburn. In that 1942 case, the Court upheld a federal penalty imposed on farmer Filburn for growing wheat for home consumption in excess of his allotment under the Second Agricultural Adjustment Act. Even though Filburn’s total production was an infinitesimally small portion of the nearly one billion bushels grown in the U.S. at that time, the Court concluded, tautologically, that the aggregate of production by all farmers had a substantial effect on the wheat market. Thus, since Congress could act on overall production, it could reach all aspects of it, even marginal producers such as Filburn. The government claimed that the ACA’s individual mandate was analogous. Even if one healthy individual’s failure to buy insurance would scarcely affect the health insurance market, a large number of such individuals and of “free riders” failing to get insurance until after a medical need arose would, in the aggregate, have such a substantial effect.

Roberts, in effect writing for himself and the formally dissenting justices on that issue, disagreed. He emphasized that Congress has only limited, enumerated powers, at least in theory. Further, Congress might enact laws needed to exercise those powers. However, such laws must not only be necessary, but also proper. In other words, they must not themselves seek to achieve objectives not permitted under the enumerated powers. As opinions in earlier cases, going back to Chief Justice John Marshall in Gibbons v. Ogden had done, Roberts emphasized that the enumeration of congressional powers in the Constitution meant that there were some things Congress could not reach.

As to the Commerce Clause itself, the Chief Justice noted that Congress previously had only used that power to control activities in which parties first had chosen to engage. Here, however, Congress sought to compel people to act who were not then engaged in commercial activity. However broad Congress’s power to regulate interstate commerce had become over the years with the Court’s acquiescence, this was a step too far. If Congress could use the Commerce Clause to compel people to enter the market of health insurance, there was no other product or service Congress could not force on the American people.

This obstacle had caused the humorous episode at oral argument where the Chief Justice inquired whether the government could require people to buy broccoli. The government urged, to no avail, that health insurance was unique, in that people buying broccoli would have to pay the grocer before they received their ware, whereas hospitals might have to provide services and never get paid. Of course, the only reason hospitals might not get paid is because state and federal laws require them to provide certain services up front, and there is no reason why laws might not be adopted in the future that require grocers to supply people with basic “healthy” foods, regardless of ability to pay. Roberts also acknowledged that, from an economist’s perspective, choosing not to participate in a market may affect that market as much as choosing to participate. After all, both reflect demand, and a boycott has economic effects just as a purchasing fad does. However, to preserve essential constitutional structures, sometimes lines must be drawn that reflect considerations other than pure economic policy.

The Chief Justice was not done, however. Having rejected the Commerce Clause as support for the ACA, he embraced Congress’s taxing power, instead. If the individual mandate was a tax, it would be upheld because Congress’s power to tax was broad and applied to individuals, assets, and income of any sort, not just to activities, as long as its purpose or effect was to raise revenue. On the other hand, if the individual mandate was a “penalty,” it could not be upheld under the taxing power, but had to be justified as a necessary and proper means to accomplish another enumerated power, such as the commerce clause. Of course, that path had been blocked in the preceding part of the opinion. Hence, everything rested on the individual mandate being a “tax.”

At first glance it appeared that this avenue also was a dead end, due to Roberts’s decision that the individual mandate was not a tax for the purpose of the Anti-Injunction Act. On closer analysis, however, the Chief Justice concluded that something can be both a tax and not be a tax, seemingly violating the non-contradiction principle. Roberts sought to escape this logical trap by distinguishing what Congress can declare as a matter of statutory interpretation and meaning from what exists in constitutional reality. Presumably, Congress can define that, for the purpose of a particular federal law, 2+2=5 and the Moon is made of green cheese. In applying a statute’s terms, the courts are bound by Congress’s will, however contrary that may be to reason and ordinary reality.

However, when the question before a court is the meaning of an undefined term in the Constitution, an “originalist” judge will attempt to discern the commonly-understood meaning of that term when the Constitution was adopted, subject possibly to evolution of that understanding through long-adhered-to judicial, legislative, and executive usage. Here, Roberts applied factors the Court had developed beginning in Bailey v. Drexel Furniture Co. in 1922. Those factors compelled the conclusion that the individual mandate was, functionally, a tax. Particularly significant for Roberts was that the ACA limited the payment to less than the price for insurance, and that it was administered by the IRS through the normal channels of tax collection. Further, because the tax would raise substantial revenue, its ancillary purpose of expanding insurance coverage was of no constitutional consequence. Taxes often affect behavior, understood in the old adage that, if the government taxes something, it gets less of it.

Roberts’s analysis reads as the constitutional law analogue to quantum mechanics and the paradox of Schroedinger’s Cat, in that the individual mandate is both a tax and a penalty until it is observed by the Chief Justice. His opinion has produced much mirth—and frustration—among commentators, and there were inconvenient facts in the ACA itself. The mandate was in the ACA’s operative provisions, not its revenue provisions, and Congress referred to the mandate as a “penalty” eighteen times in the ACA. Still, he has a valid, if not unassailable, point. A policy that has the characteristics associated with a tax ordinarily is a tax. If Congress nevertheless consciously chooses to designate it as a penalty, then for the limited purpose of assessing the policy’s connection to another statute which carefully uses a different term, here the Anti-Injunction Act, the blame for any absurdity lies with Congress.

The Medicaid expansion under the ACA was struck down. Under the Constitution, Congress may spend funds, subject to certain ill-defined limits. One of those is that the expenditure must be for the “general welfare.” Under classic republican theory, this meant that Congress could spend the revenue collected from the people of the several states on projects that would benefit the United States as a whole, not some constituent part, or an individual or private entity. It was under that conception of “general welfare” that President Grover Cleveland in 1887 vetoed a bill that appropriated $10,000 to purchase seeds to be distributed to Texas farmers hurt by a devastating drought. Since then, the phrase has been diluted to mean anything that Congress deems beneficial to the country, however remotely.

Moreover, while principles of federalism prohibit Congress from compelling states to enact federal policy—known as the “anti-commandeering” doctrine—Congress can provide incentives to states through conditional grants of federal funds. As long as the conditions are clear, relevant to the purpose of the grant, and not “coercive,” states are free to accept the funds with the conditions or to reject them. Thus, Congress can try to achieve indirectly through the spending power what it could not require directly. For example, Congress cannot, as of now, direct states to teach a certain curriculum in their schools. However, Congress can provide funds to states that teach certain subjects, defined in those grants, in their schools. The key issue usually is whether the condition effectively coerces the states to submit to the federal financial blandishment. If so, the conditional grant is unconstitutional because it reduces the states to mere satrapies of the federal government rather than quasi-sovereigns in our federal system.

In what was a judicial first, Roberts found that the ACA unconstitutionally coerced the states into accepting the federal grants. Critical to that conclusion was that a state’s failure to accept the ACA’s expansion of Medicaid would result not just in the state being ineligible to receive federal funds for the new coverage. Rather, the state would lose all of its existing Medicaid funding. As well, here the program affected—Medicaid—accounted for over 20% of the typical state’s budget. Roberts described this as “economic dragooning that leaves the States with no real option but to acquiesce in the Medicaid expansion.” Roberts noted that the budgetary impact on a state from rejecting the expansion dwarfed anything triggered by a refusal to accept federal funds under previous conditional grants.

One peculiarity of the opinions in NFIB was the stylistic juxtaposition of Roberts’s opinion for the Court and the principal dissent, penned by Justice Antonin Scalia. Roberts at one point uses “I” to defend a point of law he makes, which is common in dissents or concurrences, instead of the typical “we” or “the Court” used by a majority. By contrast, Scalia consistently uses “we” (such as “We conclude that [the ACA is unconstitutional.” and “We now consider respondent’s second challenge….”), although that might be explained because he wrote for four justices, Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and himself. He also refers to Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s broadly as “the dissent.” Most significant, Scalia’s entire opinion reads like that of a majority. He surveys the relevant constitutional doctrines more magisterially than does the Chief Justice, even where he and Roberts agree, something that dissents do not ordinarily do. He repeatedly and in detail criticizes the government’s arguments and the “friend-of the-court” briefs that support the government, tactics commonly used by the majority opinion writer.

These oddities have provoked much speculation, chiefly that Roberts initially joined Scalia’s opinion, which would have made it the majority opinion, but got cold feet. Rumor spread that Justice Anthony Kennedy had attempted until shortly before the decision was announced to persuade Roberts to rejoin the Scalia group. Once that proved fruitless, it was too late to make anything but cosmetic changes to Scalia’s opinion for the four now-dissenters. Only the justices know what actually happened, but the scenario seems plausible.

Why would Roberts do this? Had Scalia’s opinion prevailed, the ACA would have been struck down in its entirety. That would have placed the Court in a difficult position, especially during an election year, having exploded what President Obama considered his signature achievement. The President already had a fractious relationship with the Supreme Court and earlier had made what some interpreted as veiled political threats against the Court over the case. Roberts’s “switch in time” blunted that. The chief justice is at most primus inter pares, having no greater formal powers than his associates. But he is often the public and political figurehead of the Court. Historically, chief justices have been more “political” in the sense of being finely attuned to maintaining the institutional vitality of the Court. John Marshall, William Howard Taft, and Charles Evans Hughes especially come to mind. Associate justices can be jurisprudential purists, often through dissents, to a degree a chief justice cannot.

Choosing his path allowed Roberts to uphold the ACA in part, while striking jurisprudential blows against the previously constant expansion of the federal commerce and spending powers. Even as to the taxing power, which he used to uphold that part of the ACA, Roberts planted a constitutional land mine. Should the mandate ever be made really effective, if Congress raised it above the price of insurance, the “tax” argument would fail and a future court could strike it down as an unconstitutional penalty. Similarly, if the tax were repealed, as eventually happened, and the mandate were no longer supported under the taxing power, it could threaten the entire ACA.

After NFIB, attempts to modify or eliminate the ACA through legislation or litigation continued, with mixed success. Noteworthy is that the tax payment for the individual mandate was repealed in 2017. This has produced a new challenge to the ACA as a whole, because the mandate is, as the government conceded in earlier arguments, a crucial element of the whole health insurance structure. The constitutional question is whether the mandate is severable from the rest of the ACA. The district court held that the mandate was no longer a tax and, thus, under NFIB, is unconstitutional. Further, because of the significance that Congress attached to the mandate for the vitality of the ACA, the mandate could not be severed from the ACA, and the entire law is unconstitutional. The Fifth Circuit agreed that the mandate is unconstitutional, but disagreed about the extent that affects the rest of the ACA. The Supreme Court will hear the issue in its 2020-2021 term in California v.. Texas.

On the political side, the American public seems to support the ACA overall, although, or perhaps because, it has been made much more modest than its proponents had planned. So, the law, somewhat belatedly and less boldly, achieved a key goal of President Obama’s agenda. That success came at a stunning political cost to the President’s party, however. The Democrats hemorrhaged over 1,000 federal and state legislative seats during Obama’s tenure. In 2010 alone, they lost a historic 63 House seats, the biggest mid-term election rout since 1938, plus 6 Senate seats. The moderate “blue-dog” Democrats who had been crucial to the passage of the ACA were particularly hard hit. Whatever the ACA’s fate turns out to be in the courts, the ultimate resolution of controversial social issues remains with the people, not lawyers and judges.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

September 11, 2001: Islamic Terrorists Attack New York City and Washington, D.C.

90 in 90 2020, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Scot Faulkner September 11, 2001: Islamic Terrorists Attack New York City and Washington, D.C. – Guest Essayist: Scot Faulkner, 10. Dates in American History, 2020 - Dates in American History, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Scot FaulknerFor those old enough to remember, September 11, 2001, 9:03 a.m. is burned into our collective memory. It was at that moment that United Flight 175 crashed into the South Tower of the World Trade Center in New York City.

Everyone was watching. American Airlines Flight 11 had crashed into the North Tower seventeen minutes earlier. For those few moments there was uncertainty whether the first crash was a tragic accident. Then, on live television, the South Tower fireball vividly announced to the world that America was under attack.

The nightmare continued. As horrifying images of people trapped in the burning towers riveted the nation, news broke at 9:37 a.m. that American Flight 77 had plowed into the Pentagon.

For the first time since December 11, 1941, Americans were collectively experiencing full scale carnage from a coordinated attack on their soil.

The horror continued as the twin towers collapsed, sending clouds of debris throughout lower Manhattan and igniting fires in adjoining buildings. Questions filled the minds of government officials and every citizen: How many more planes? What were their targets? How many have died? Who is doing this to us?

At 10:03 a.m., word came that United Flight 93 had crashed into a Pennsylvania field. Speculation exploded as to what happened. Later investigations revealed that Flight 93 passengers, alerted by cell phone calls of the earlier attacks, revolted causing the plane to crash. Their heroism prevented this final hijacked plane from destroying the U.S. Capitol Building.

That final accounting was devastating: 2,977 killed and over 25,000 injured. The death toll continues to climb to this day as first responders and building survivors perish from respiratory conditions caused by inhaling the chemical-laden smoke. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in human history.

How this happened, why this happened, and what happened next compounds the tragedy.

Nineteen terrorists, most from Saudi Arabia, were part a radical Islamic terrorist organization called al-Qaeda “the Base.” This was the name given the training camp for the radical Islamicists who fought the Soviets in Afghanistan.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, a Pakistani, was the primary organizer of the attack. Osama Bin Laden, a Saudi, was the leader and financier. Their plan was based upon an earlier failed effort in the Philippines. It was mapped out in late 1998. Bin Laden personally recruited the team, drawn from experienced terrorists. They insinuated themselves into the U.S., with several attending pilot training classes. Five-man teams would board the four planes, overpower the pilots, and fly them as bombs into significant buildings.

They banked on plane crews and passengers responding to decades of “normal” hijackings. They would assume the plane would be commandeered, flown to a new location, demands would be made, and everyone would live. This explains the passivity on the first three planes. Flight 93 was different, because it was delayed in its departure, allowing time for passengers to learn about the fate of the other planes. Last minute problems also reduced the Flight 93 hijacker team to only four.

The driving force behind the attack was Wahhabism, a highly strict, anti-Western version of Sunni Islam.

The Saudi Royal Family owes its rise to power to Muhammad ibn Abd al-Wahhab (1703-1792). He envisioned a “pure” form of Islam that purged most worldly practices (heresies), oppressed women, and endorsed violence against nonbelievers (infidels), including Muslims who differed with his sect. This extremely conservative and violent form of Islam might have died out in the sands of central Arabia were in not for a timely alliance with a local tribal leader, Muhammad bin Saud.

The House of Saud was just another minor tribe, until the two Muhammads realized the power of merging Sunni fanaticism with armed warriors. Wahhab’s daughter married Saud’s son, merging their two blood lines to this day. The House of Saud and its warriors rapidly expanded throughout the Arabia Peninsula, fueled by Wahhabi fanaticism. These various conflicts always included destruction of holy sites of rival sects and tribes. While done in the name of “purification,” the result was erasing the physical touchstones of rival cultures and governments.

In the early 20th Century, Saudi leader, ibn Saud, expertly exploited the decline of the Ottoman Empire, and alliances with European Powers, to consolidate his permanent hold over the Arabian Peninsula. Control of Mecca and Medina, Islam’s two holiest sites, gave the House of Saud the power to promote Wahhabism as the dominant interpretation of Sunni Islam. This included internally contradictory components of calling for eradicating infidels while growing rich from Christian consumption of oil and pursuing lavish hedonism when not in public view.

In the mid-1970s Saudi Arabia used the flood of oil revenue to become the “McDonalds of Madrassas.” Religious schools and new Mosques popped up throughout Africa, Asia, and the Middle East. This building boom had nothing to do with education and everything to do with spreading the cult of Wahhabism. Pakistan became a major hub for turning Wahhabi madrassas graduates into dedicated terrorists.

Wahhabism may have remained a violent, dangerous, but diffused movement, except it found fertile soil in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan was called the graveyard of empires as its rugged terrain and fierce tribal warriors thwarted potential conquerors for centuries. In 1973, the last king of Afghanistan was deposed leading to years of instability. In April 1978, the opposition Communist Party seized control in a bloody coup. The communist tried to brutally consolidate power, which ignited a civil war among factions supported by Pakistan, China, Islamists (known as the Mujahideen), and the Soviet Union. Amidst the chaos, U.S. Ambassador Adolph Dubbs was killed on February 14, 1979.

On December 24, 1979, the Soviet Union invaded Afghanistan, killing their ineffectual puppet President, and ultimately bringing over 100,000 military personnel into the country. What followed was a vicious war between the Soviet military and various Afghan guerrilla factions. Over 2 million Afghans died.

The Reagan Administration covertly supported the anti-Soviet Afghan insurgents, primarily aiding the secular pro-west Northern Alliance. Arab nations supported the Mujahideen. Bin Laden entered the insurgent caldera as a Mujahideen financier and fighter. By 1988, the Soviets realized their occupation had failed. They removed their troops, leaving behind another puppet government and Soviet trained military.

When the Soviet Union collapsed, Afghanistan was finally free. Unfortunately, calls for reunifying the country by reestablishing the monarchy and strengthening regional leadership went unheeded. Attempts at recreating the pre-invasion faction ravaged parliamentary system only led to new rounds of civil war.

In September 1994, the weak U.S. response opened the door for the Taliban, graduates from Pakistan’s Wahhabi madrassas, to launch their crusade to take control of Afghanistan. By 1998, the Taliban controlled 90% of the country.

Bin Laden and his al-Qaeda warriors made Taliban-controlled territory in Afghanistan their new base of operations. In exchange, Bin Laden helped the Taliban eliminate their remaining opponents. This was accomplished on September 9, 2001, when suicide bombers disguised as a television camera crew blew-up Ahmad Shah Massoud, the charismatic pro-west leader of the Northern Alliance.

Two days later, Bin Laden’s plan to establish al-Qaeda as the global leader of Islamic terrorism was implemented with hijacking four planes and turning them into guided bombs.

The 9-11 attacks, along with the earlier support against the Soviets in Afghanistan, was part of Bin Laden’s goal to lure infidel governments into “long wars of attrition in Muslim countries, attracting large numbers of jihadists who would never surrender.” He believed this would lead to economic collapse of the infidels, by “bleeding” them dry. Bin Laden outlined his strategy of “bleeding America to the point of bankruptcy” in a 2004 tape released through Al Jazeera.

On September 14, amidst the World Trade Center rubble, President George W. Bush addressed those recovering bodies and extinguishing fires using a bullhorn:

“The nation stands with the good people of New York City and New Jersey and Connecticut as we mourn the loss of thousands of our citizens”

A rescue worker yelled, “I can’t hear you!”

President Bush spontaneously responded: “I can hear you! The rest of the world hears you! And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon!”

Twenty-three days later, on October 7, 2001, American and British warplanes, supplemented by cruise missiles fired from naval vessels, began destroying Taliban operations in Afghanistan.

U.S. Special Forces entered Afghanistan. Working the Northern Alliance, they defeated major Taliban units. They occupied Kabul, the Afghan Capital, on November 13, 2001.

On May 2, 2011, U.S. Special Forces raided an al-Qaeda compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, killing Osama bin Laden.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

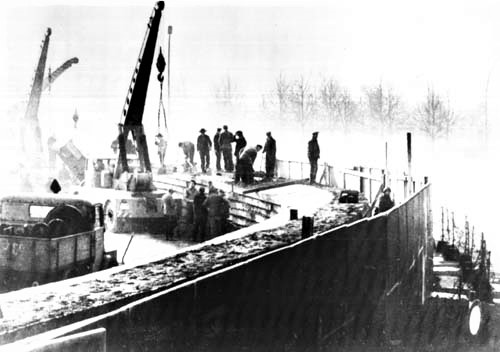

Fall of the Berlin Wall and End of the Cold War

The Honorable Don Ritter, 90 in 90 2020, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog Fall of the Berlin Wall and End of the Cold War – Guest Essayist: The Honorable Don Ritter, The Honorable Don Ritter, 10. Dates in American History, 2020 - Dates in American History, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day StudiesIn October of 1989, hundreds of thousands of East German citizens demonstrated in Leipzig, following a pattern of demonstrations for freedom and human rights throughout Eastern Europe and following the first ever free election in a Communist country, Poland, in the Spring of 1989. Hungary had opened its southern border with Austria and East Germans seeking a better life were fleeing there. Czechoslovakia had done likewise on its western border and the result was the same.

The East German government had been on edge and was seeking to reduce domestic tensions by granting limited passage of its citizens to West Germany. And that’s when the dam broke.

On November 9, 1989, thousands of elated East Berliners started pouring into West Berlin. There was a simple bureaucratic error earlier in the day when an East German official read a press release he hadn’t previously studied and proclaimed that residents of Communist East Berlin were permitted to cross into West Berlin, freely and, most importantly, immediately. He had missed the end of the release which instructed that passports would be issued in an orderly fashion when government offices opened the next day.

This surprising information about free passage was spread throughout East Berlin, East Germany and, indeed, around the word like a lightning bolt. Massive crowds gathered near-instantaneously and celebrated at the heavily guarded Wall gates which, in a party-like atmosphere amid total confusion, were opened by hard core communist yet totally outmanned Border Police, who normally had orders to shoot-to-kill anyone attempting to escape. A floodgate was opened and an unstoppable flood of freedom-seeking humanity passed through, unimpeded.

Shortly thereafter, the people tore down the Wall with every means available. The clarion bell had been sounded and the reaction across communist Eastern Europe was swift. Communist governments fell like dominoes.

The Wall itself was a glaring symbol of totalitarian communist repression and the chains that bound satellite countries to the communist Soviet Union. But the “bureaucratic error” of a low-level East German functionary was the match needed to set off an explosion of freedom that had been years in-the-making throughout the 1980s. And that is critical to understanding just why the Cold War came to an end, precipitously and symbolically, with the fall of the Wall.

With the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency of the United States, Margaret Thatcher to Prime Minister of Great Britain and the Polish Cardinal, Jean Paul II becoming Pope of the Roman Catholic Church, the foundation was laid in the 1980s for freedom movements in Soviet Communist-dominated Eastern Europe to evolve and grow. Freedom lovers and fighters had friends in high places who believed deeply in their cause. These great leaders of the West understood the enormous human cost of communist rule and were eager to fight back in their own unique and powerful way, leading their respective countries and allies in the process.

Historic figures like labor leader Lech Walesa, head of the Polish Solidarity Movement and Czech playwright Vaclav Havel, an architect of the Charter 77 call for basic human rights had already planted the seeds for historic change. Particularly in Poland, the combination of Solidarity and the Catholic Church, supported staunchly in the non-communist world by Reagan and Thatcher, anti-communism flourished despite repression and brutal crackdowns.

And then, there was a new General Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, Mikhail Gorbachev. When he came to power in 1985, he sought to exhort workers to increase productivity in the economy, stamp out the resistance to Soviet occupation in Afghanistan via a massive bombing campaign and keep liquor stores closed till 2:00 pm. However, exhortation didn’t work and the economy continued to decline, Americans gave Stinger missiles to the Afghan resistance and the bombing campaign failed and liquor stores were being regularly broken into by angry citizens not to be denied their vodka. The Afghan war was a body blow to a Soviet military, ‘always victorious’ and Soviet mothers protested their sons coming back in body bags. The elites (“nomenklatura”) were taken aback and demoralized by what was viewed as a military debacle in a then Fourth World country. “Aren’t we supposed to be a superpower?”

Having failed at run-of-the-mill Soviet responses to problems, Gorbachev embarked on a bold-for-the-USSR effort to restructure the failing Soviet economy via Perestroika which sought major reform but within the existing burdensome central-planning bureaucracy. On the political front, he introduced Glasnost, opening discussion of social and economic problems heretofore forbidden since the USSR’s beginning. Previously banned books were published. Working and friendly relationships with President Reagan and Margaret Thatcher were also initiated.

In the meantime, America under President Reagan’s leadership was not only increasing its military strength in an accelerated and expensive arms race but was also opposing Soviet-backed communist regimes and their so-called “wars of national liberation” all over the world. The cold war turned hot under the Reagan Doctrine. President Reagan also pushed “Star Wars,” an anti-ballistic missile system that could potentially neutralize Soviet long-range missiles. Star Wars, even if off in the future, worried Gorbachev’s military and communist leadership of an electronically and computer technology-challenged Soviet Union.

Competing economically and militarily with a resurgent anti-communist American engine firing on all cylinders became too expensive for the economically and technologically disadvantaged Soviet Union. There are those who say the USSR collapsed of its own weight, but they are wrong. If that were so, a congenitally overweight USSR would have collapsed a lot earlier. Gorbachev deserves a lot of credit to be sure but there should be no doubt, he and the USSR were encouraged to shift gears and change course. Unfortunately for communist rulers, their reforms initiated a downward spiral in their ability to control their citizens. Totalitarian control was first diminished and then lost. Author’s note: A lesson which was not lost on the rulers of Communist China.

Summing up: A West with economic and military backbone plus spiritual leadership, combined with brave dissident and human rights movements in Eastern Europe and the USSR itself, forced changes in behavior of the communist monolith. Words and deeds mattered. When Ronald Reagan called the Soviet Union an “evil empire” before the British Parliament, the media and political opposition worldwide was aghast… but in the Soviet Gulag, political prisoners rejoiced. When President Reagan said “Mr. Gorbachev, tear down this wall,” consternation reigned in the West… but the people from East Germany to the Kremlin heard it loud and clear.

And so fell the Berlin Wall.

The Honorable Don Ritter, Sc. D., served seven terms in the U.S. Congress from Pennsylvania including both terms of Ronald Reagan’s presidency. Dr. Ritter speaks fluent Russian and lived in the USSR for a year as a Nation Academy of Sciences post-doctoral Fellow during Leonid Brezhnev’s time. He served in Congress as Ranking Member of the Congressional Helsinki Commission and was a leader in Congress in opposition to the Soviet invasion and occupation of Afghanistan.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

August 2 1990 Persian Gulf War Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm Begins Guest Essayist Danny de Gracia

90 in 90 2020, 6. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, Blog, Danny de Gracia August 2, 1990: Persian Gulf War (Operation Desert Shield and Operation Desert Storm) Begins – Guest Essayist: Danny de Gracia, 10. Dates in American History, 2020 - Dates in American History, 13. Guest Constitutional Scholar Essayists, 90 Day Studies, Danny de GraciaIt’s hard to believe that this year marks thirty years since Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait in August of 1990. In history, some events can be said to be turning points for civilization that set the world on fire, and in many ways, our international system has not been the same since the invasion of Kuwait.

Today, the Iraq that went to war against Kuwait is no more, and Saddam Hussein himself is long dead, but the battles that were fought, the policies that resulted, and the history that followed is one that will haunt the world for many more years to come.

Iraq’s attempts to annex Kuwait in 1990 would bring some of the most powerful nations into collision, and would set in motion a series of events that would give rise to the Global War on Terror, the rise of ISIS, and an ongoing instability in the region that frustrates the West to this day.

To understand the beginning of this story, one must go back in time to the Iranian Revolution in 1979, where a crucial ally of the United States of America at the time – Iran – was in turmoil because of public discontent with the leadership of its shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi.

Iran’s combination of oil resources and strategic geographic location made it highly profitable for the shah and his allies in the West over the years, and a relationship emerged where Iran’s government, flush with oil money, kept America’s defense establishment in business.

For years, the shah had been permitted to purchase nearly any American weapons system he pleased, no matter how advanced or powerful it may be, and Congress was only all too pleased to give it to him.

The Vietnam War had broken the U.S. military and hollowed out the resources of the armed services, but the defense industry needed large contracts if was to continue to support America.

Few people realize that Iran, under the Shah, was one of the most important client states in the immediate post-Vietnam era, making it possible for America to maintain production lines of top-of-the-line destroyers, fighter planes, engines, missiles, and many other vital elements of the Cold War’s arms race against the Soviet Union. As an example, the Grumman F-14A Tomcat, America’s premier naval interceptor of 1986 “Top Gun” fame, would never have been produced in the first place if it were not for the commitment of the Iranians as a partner nation in the first batch of planes.

When the Iranian Revolution occurred, an embarrassing ulcer to American interests emerged in Western Asia, as one of the most important gravity centers of geopolitical power had slipped out of U.S. control. Iran, led by an ultra-nationalistic religious revolutionary government, and armed with what was at the time some of the most powerful weapons in the world, had gone overnight from trusted partner to sworn enemy.

Historically, U.S. policymakers typically prefer to contain and buffer enemies rather than directly opposing them. Iraq, which had also gone through a regime change in July of 1979 with the rise of Saddam Hussein in a bloody Baath Party purge, was an rival to Iran, making it a prime candidate to be America’s new ally in the Middle East.

The First Persian Gulf War: A Prelude

Hussein, a brutal, transactional-minded leader who rose to power through a combination of violence and political intrigue, was one to always exploit opportunities. Recognizing Iran’s potential to overshadow a region he himself deemed himself alone worthy to dominate, Hussein used the historical disagreement over ownership of the strategic, yet narrow Shatt al-Arab waterway that divided Iran from Iraq to start a war on September 22, 1980.

Iraq, flush with over $33 billion in oil profits, had become formidably armed with a modern military that was supplied by numerous Western European states and, bizarrely, even the Soviet Union as well. Hussein, like Nazi Germany’s Adolf Hitler, had a fascination for superweapons and sought to amass a high-tech military force that could not only crush Iran, but potentially take over the entire Middle East.

In Hussein’s bizarre arsenal would eventually include everything from modified Soviet ballistic missiles (the “al-Hussein”) to Dassault Falcon 50 corporate jets modified to carry anti-ship missiles, a nuclear weapons program at Osirak, and even work on a supergun capable of firing telephone booth-sized projectiles into orbit nicknamed Project Babylon.

Assured of a quick campaign against Iran and tacitly supported by the United States, Hussein saw anything but a decisive victory, and spent almost a decade in a costly war of attrition with Iran. Hussein, who constantly executed his own military officers for making tactical withdrawals or failing in combat, denied his military the ability to learn from defeats and handicapped his army by his own micromanagement.

Iraq’s Pokémon-like “gotta catch ‘em all” model of military procurement during the war even briefly put it at odds with the United States on May 17, 1987, when one of its heavily armed Falcon 50 executive jets, disguised on radar as a Mirage F1EQ fighter, accidentally launched a French-acquired Exocet missile against a U.S. Navy frigate, the USS Stark. President Ronald Reagan, though privately horrified at the loss of American sailors, still considered Iraq a necessary counterweight to Iran, and used the Stark incident to increase political pressure on Iran.

While Iraq had begun its war against Iran in the black, years of excessive military spending, meaningless battles, and rampant destruction of the Iraqi army had taken its toll. Hussein’s war had put the country in over $37 billion dollars in debt, much of which had been owed to neighboring Kuwait.

Faced with a strained economy, tens of thousands of soldiers returning wounded from the war, and a military that was virtually on the brink of deposing Saddam Hussein just as he had deposed his predecessor Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr in 1979, Iraq had no choice but to end its war against Iran.

Both Iran and Iraq would ultimately submit to a UN brokered ceasefire, but ironically, what would be one of the decisive elements in bringing the first Persian Gulf war to a close would not be the militaries of either country, but the U.S. military, when it launched a crippling air and naval attack against Iranian forces on April 18, 1988.

Iran, which had mined important sailing routes of the Persian Gulf as part of its area denial strategy during the war, succeeded on April 14, 1988 in striking the USS Samuel B. Roberts, an American frigate deployed to the region to protect shipping.

In response, the U.S. military retaliated with Operation: Praying Mantis which hit Iranian oil platforms (which had since been reconfigured as offensive gun platforms), naval vessels, and other military targets. The battle, which was so overwhelming in its scope that it actually was and remains to this day as the largest carrier and surface ship battle since World War II, resulted in the destruction of most of Iran’s navy and was a major contributing factor in de-fanging Iran for the next decade to come.

Kuwait and Oil

Saddam Hussein, claiming victory over Iran amidst the UN ceasefire, and now faced with a new U.S. president, George H.W. Bush in 1989, felt that the time was right to consolidate his power and pull his country back from collapse. In Hussein’s mind, he had been the “savior” of the Arab and Gulf States, who had protected them during the Persian Gulf war against the encroachment of Iranian influence. As such, he sought from Kuwait a forgiveness of debts incurred in the war with Iran, but would find no such sympathy. The 1990s were just around the corner, and Kuwait had ambitions of its own to grow in the new decade as a leading economic powerhouse.

Frustrated and outraged by what he perceived was a snub, Hussein reached into his playbook of once more leveraging territorial disputes for political gain and accused Kuwait of stealing Iraqi oil by means of horizontal slant drilling into the Rumaila oil fields of southern Iraq.

Kuwait found itself in an unenviable situation neighboring the heavily armed Iraq, and as talks over debt and oil continued, the mighty Iraqi Republican Guard appeared to be gearing up for war. Most political observers at the time, including many Arab leaders, felt that Hussein was merely posturing and that it was a grand bluff to maintain his image as a strong leader. For Hussein to invade a neighboring Arab ally was unthinkable at the time, especially given Kuwait’s position as an oil producer.

On July 25, 1990, U.S. Ambassador to Iraq, April Glaspie, met with President Saddam Hussein and his deputy, Tariq Aziz on the topic of Kuwait. Infamously, Glaspie is said to have told the two, “We have no opinion on your Arab/Arab conflicts, such as your dispute with Kuwait. Secretary Baker has directed me to emphasize the instruction, first given to Iraq in the 1960s, that the Kuwait issue is not associated with America.”

While the George H.W. Bush administration’s intentions were obviously aimed at taking no side in a regional territorial dispute, Hussein, whose personality was direct and confrontational, likely interpreted the Glaspie meeting as America backing down.

In the Iraqi leader’s eyes, one always takes the initiative and always shows an enemy their dominance. For a powerful country such as the United States to tell Hussein that it had “no opinion” on Arab/Arab conflict, this was most likely a sign of permission or even weakness that the Iraqi leader felt he had to exploit.

America, still reeling from the shadow of the Vietnam War failure and the disastrous Navy SEAL incident in Operation: Just Cause in Panama, may have appeared in that moment to Hussein as a paper tiger that could be out-maneuvered or deterred by aggressive action. Whatever the case was, Iraq stunned the world when just days later on August 2, 1990 it invaded Kuwait.

The Invasion of Kuwait

American military forces and intelligence agencies had been closely monitoring the buildup of Iraqi forces for what appeared like an invasion of Kuwait, but it was still believed right up to the moment of the attack that perhaps Saddam Hussein was only bluffing. The United States Central Command had set WATCHCON 1 – or Watch Condition One – the highest state of non-nuclear alertness in the region just prior to Iraq’s attack, and was regularly employing satellites, reconnaissance aircraft, and electronic surveillance platforms to observe the Iraqi Army.

Nevertheless, if there is one mantra that perfectly encapsulates the posture of the United States and European powers from the beginnings of the 20th century to the present, it is “Western countries too slow to act.” As is often the result with aggressive nations that challenge the international order, Iraq plowed into Kuwait and savaged the local population.

While America and her allies have always had the best technologies, the best weapons, and the best early warning systems or sensors, these historically for more than a century have been rendered useless because they often provide information that is not actionably employed to stop an attack or threat. Such was the case with Iraq, where all of the warning signs were present that an attack was imminent, but no action was taken to stop them.

Kuwait’s military courageously fought Iraq’s invading army, and even notably fought air battles with their American-made A-4 Skyhawks, some of them launching from highways after their air bases were destroyed. But the Iraqi army, full of troops who had fought against Iran and equipped with the fourth largest military in the world at that time, was simply too powerful to overcome. 140,000 Iraqi troops flooded into Kuwait and seized one of the richest oil producing nations in the region.

As Hussein’s military overran Kuwait, sealed its borders, and began plundering the country and ravaging its civilian population, the worry of the United States immediately shifted from Kuwait to Saudi Arabia, for fear that the kingdom might be next. On August 7, 1990, President Bush commenced “Operation: Desert Shield,” a military operation to defend Saudi Arabia and prevent any further advance of the Iraqi army.

At the time that Operation: Desert Shield commenced, I was living in Hampton Roads, Virginia and my father was a lieutenant colonel assigned to Tactical Air Command headquarters at the nearby Langley Air Force Base, and 48 F-15 Eagle fighter planes from that base immediately deployed to the Middle East in support of that operation. In the days that followed, our base became a flurry of activity and I remember seeing a huge buildup of combat aircraft from all around the United States forming at Langley.

President Bush, who himself had been a fighter pilot and U.S. Navy officer who fought in World War II, was all too familiar with what could happen when a megalomaniacal dictator started invading their neighbors. Whatever congeniality of convenience existed between the U.S. and Iraq to oppose Iran was now a thing of the past in the wake of the occupation of Kuwait.

Having fought against both the Nazis and Imperial Japanese in WWII, Bush saw many similarities of Adolf Hitler in Saddam Hussein, and immediately began comparing the Iraqi leader and his government to the Nazis in numerous speeches and public appearances as debates raged over what the U.S. should do regarding Kuwait.

As retired, former members of previous presidential administrations urged caution and called for long-term sanctions on Iraq rather than a kinetic military response, the American public, still captivated by the Vietnam experience, largely felt that the matter in Kuwait was not a concern that should involve military forces. Protests began to break out across America with crowds shouting “Hell no, we won’t go to war for Texaco” and others singing traditional protest songs of peace like “We Shall Overcome.”

Bush, persistent in his beliefs that Iraq’s actions were intolerable, made every effort to keep taking the moral case for action to the American public in spite of these pushbacks. As a leader seasoned by the horrors of war and combat, Bush must have known, as Henry Kissinger once said, that leadership is not about popularity polls, but about “an understanding of historical cycles and courage.”

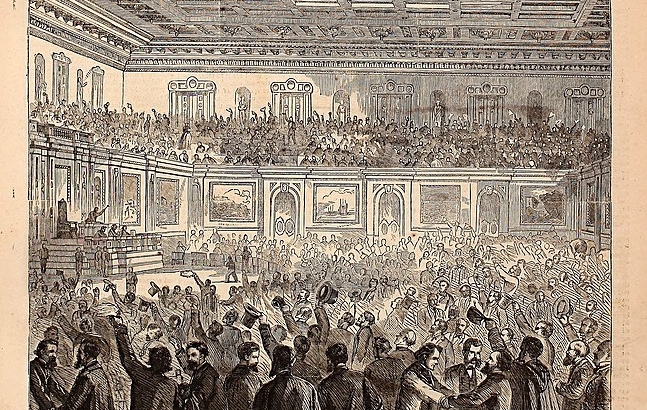

On September 11, 1990, before a joint session of Congress, Bush gave a fiery address that to this day still stands as one of the most impressive presidential addresses in history.

“Vital issues of principle are at stake. Saddam Hussein is literally trying to wipe a country off the face of the Earth. We do not exaggerate,” President Bush would say before Congress. “Nor do we exaggerate when we say Saddam Hussein will fail. Vital economic interests are at risk as well. Iraq itself controls some 10 percent of the world’s proven oil reserves. Iraq, plus Kuwait, controls twice that. An Iraq permitted to swallow Kuwait would have the economic and military power, as well as the arrogance, to intimidate and coerce its neighbors, neighbors who control the lion’s share of the world’s remaining oil reserves. We cannot permit a resource so vital to be dominated by one so ruthless, and we won’t!”

Members of Congress erupted in roaring applause at Bush’s words, and he issued a stern warning to Saddam Hussein: “Iraq will not be permitted to annex Kuwait. And that’s not a threat, that’s not a boast, that’s just the way it’s going to be.”

Ejecting Saddam from Kuwait

As America prepared for action, in Saudi Arabia, another man would also be making promises to defeat Saddam Hussein and his military. Osama bin Laden, who had participated in the earlier war in Afghanistan as part of the Mujahideen that resisted the Soviet occupation, now offered his services to Saudi Arabia, pledging to use a jihad to force Iraq out of Kuwait in the same way that he had forced the Soviets out of Afghanistan. The Saudis, however, would hear none of it; having already received the protection of the United States and its powerful allies, bin Laden, seen as a useless bit player on the world stage, was brushed aside.

Herein the seeds for a future conflict would be sown, as not only did bin Laden take offense to being rejected by the Saudi government, but the presence of American military forces on holy Saudi soil was seen as blasphemous to him and a morally corrupting influence on the Saudi people.

In fact, the presence of female U.S. Air Force personnel in Saudi Arabia seen without traditional cover or driving around in vehicles, caused many Saudi women to begin petitioning their government – and even in some instances, committing acts of civil disobedience – for more rights. This caused even more outrage among a number of fundamentalist groups in Saudi Arabia, and lent additional support, albeit covert in some instances, to bin Laden and other jihadist leaders.

Despite these cultural tensions boiling beneath the surface, President Bush successfully persuaded not only his own Congress but the United Nations as well to empower the formation of a global coalition of 35 nations to eject Iraqi occupying forces from Kuwait and to protect Saudi Arabia and the rest of the Gulf from further aggression.

On November 29, 1990, the die was cast when the United Nations passed Resolution 678, authorizing “Member States co-operating with the Government of Kuwait, unless Iraq on or before 15 January 1991 [withdraws from Kuwait] … to use all necessary means … to restore international peace and security in the area.”

Subsequently, on January 15, 1991, President Bush issued an ultimatum to Saddam Hussein to leave Kuwait. Hussein ignored the threat, believing that America was weak, and its public easily susceptible to knee-jerk reactions at the sight of losing soldiers from its prior experience in Vietnam. Hussein believed that he could not only cause the American people to back down, but that he could unravel Arab support for the UN coalition by enticing Israel to attack Iraq. As such, he persisted in occupying Kuwait and boasted that a “Mother of all Battles” was to commence, in which Iraq would emerge victorious.

History, however, shows us that this was not the case, and days later on the evening of January 16, 1991, Operation: Desert Shield became Operation: Desert Storm, when a massive aerial bombardment and air superiority campaign commenced against Iraqi forces. Unlike prior wars which combined a ground invasion with supporting air forces, the start of Desert Storm was a bombing campaign that consisted of heavy attacks by aircraft and naval-launched cruise missiles against Iraq.

The operational name “Desert Storm” may have in part been influenced by a war plan developed months earlier by Air Force planner, Colonel John A. Warden who conceived an attack strategy named “Instant Thunder” which used conventional, non-nuclear airpower in a precise manner to topple Iraqi defenses.

A number of elements from Warden’s top secret plan were integrated into the opening shots of Desert Storm’s air campaign, as U.S. and coalition aircraft knocked out Iraqi radars, missile sites, command headquarters, power stations, and other key targets in just the first night alone.

Unlike the Vietnam air campaigns which were largely political and gradual escalations of force, the Air Force, having suffered heavy losses in Vietnam, wanted as General Chuck Horner would later explain, “instant” and “maximum” escalation so that their enemies could not have time to react or rearm.

This was precisely what happened, such to the point that the massive Iraqi air force would be either annihilated by bombs on the ground, shot down by coalition combat air patrols, or forced to flee into neighboring Iran.

A number of radical operations and new weapons were employed in the air campaign of Desert Storm. For one, the U.S. Air Force had secretly converted a number of nuclear AGM-86 Air Launched Cruise Missiles (ALCMs) into conventional, high explosive precision guided missiles and equipped them on 57 B-52 bombers for a January 17 night raid called Operation: Senior Surprise.

Known internally and informally to the B-52 pilots as “Operation: Secret Squirrel,” the cruise missiles knocked out numerous Iraqi defenses and opened the door for more coalition aircraft to surge against Saddam Hussein’s military.

The Navy also employed covert strikes against Iraq, also firing BGM-109 Tomahawk Land Attack Missiles (TLAMs) that had also been converted to carry high explosive (non-nuclear) warheads. Because the early BGM-109s were guided and aimed by a primitive digital scene matching area correlator (DSMAC) that took digital photos of the ground below and compared it with pre-programmed topography in its terrain computer, the flat deserts of Iraq were thought to be problematic in employing cruise missiles, so the Navy came up with a highly controversial solution: secretly fire cruise missiles into Iran – a violation of Iranian airspace and international law – then turn them towards the mountain ranges as aiming points, and fly them into Iraq.

The plan worked, however, and the Navy would ultimately rain down on Iraq some 288 TLAMs that destroyed hardened hangars, runways, parked aircraft, command buildings, and scores of other targets in highly accurate strikes.

Part of the air war came home personally to me when a U.S. Air Force B-52, serial number 58-0248, participated in a night time raid over Iraq when it was accidentally fired upon by a friendly F-4G “Wild Weasel” that mistook the lumbering bomber’s AN/ASG-21 radar-guided tail gun as an Iraqi air defense platform. The Wild Weasel fired an AGM-88 High-speed Anti-Radiation Missile (HARM) at the B-52 that hit and exploded in its tail, but still left the aircraft in flyable condition.

At the time, my family had moved to Andersen AFB in Guam, and 58-0248 made for Guam to land for repairs. When the B-52 arrived, it was parked in a cavernous hangar and crews immediately began patching up the aircraft. My father, always wanting to ensure that I learned something about the real world so I could get an appreciation for America, brought me to the hangar to see the stricken B-52, which was affectionately given the nickname “In HARM’s Way.”

I never forgot that moment, and it caused me to realize that the war was more than just some news broadcast we watched on TV, and that war had real consequences for not only those who fought in it, but people back home as well. I remember feeling an intense surge of pride as I saw that B-52 parked in the hangar, and I felt that I was witnessing history in action.

Ultimately, the air war against Saddam Hussein’s military would go on for a brutal six weeks, leaving many of his troops shell-shocked, demoralized, and eager to surrender. In fighting Iran for a decade, the Iraqi army had never known the kind of destructive scale or deadly precision that coalition forces were able to bring to bear against them.

Once the ground campaign commenced against Iraqi forces on February 24, 1991, that portion of Operation: Desert Storm only lasted a mere 100 hours before a cease-fire would be called, not because Saddam Hussein had pleaded for survival, but because back in Washington, D.C., national leaders watching the war on CNN began to see a level of carnage that they were not prepared for.

Gen. Colin Powell, seeing that most of the coalition’s UN objectives had been essentially achieved, personally lobbied for the campaign to wrap up, feeling that further destruction of Iraq would be “unchivalrous” and fearing the loss of any more Iraqi or American lives. It was also feared that if America had actually tried to make a play for regime change in Iraq in 1991, that the Army would be left holding the bag in securing and rebuilding the country, something that not only would be costly, but might turn the Arab coalition against America. On February 28, 1991, the U.S. officially declared a cease-fire.

The Aftermath

Operation: Desert Storm successfully accomplished the UN objectives that were established for the coalition forces and it liberated Kuwait. But a number of side effects of the war would follow that would haunt America and the rest of the world for decades to come.

First, Saddam Hussein remained in power. As a result, the U.S. military would remain in the region for years as a defensive contingent, not only continuing to inflame existing cultural tensions in Saudi Arabia, but also becoming a target for jihadist terrorist attacks, including the Khobar Towers bombing on June 25, 1996 and the USS Cole bombing on October 12, 2000.

Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda terrorist group would ultimately change the modern world as we knew it when his men hijacked commercial airliners and flew them into the Pentagon and World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. It should not be lost on historical observers that 15 of the 19 hijackers that day were Saudi citizens, a strategic attempt by bin Laden to drive a wedge between the United States and Saudi Arabia to get American military forces out of the country.

9/11 would also provide an opportunity for George H.W. Bush’s son, President George W. Bush, to attempt to take down Saddam Hussein. Many of the new Bush Administration members were veterans of the previous one during Desert Storm, and felt that the elder Bush’s decision not to “take out” the Iraqi dictator was a mistake. And while the 2003 campaign against Iraq was indeed successful in taking down the Baathist-party rule in Iraq and changing the regime, it allowed many disaffected former Iraqi officers and jihadists to rise up against the West, which ultimately led to the rise of ISIS in the region.

It is my hope that the next generation of college and high school students who read this essay and reflect on world affairs will understand that history is often complex and that every action taken leaves ripples in our collective destinies. A Holocaust survivor once told me, “There are times when the world goes crazy, and catches on fire. Desert Storm was one such time when the world caught on fire.”

What can we learn from the invasion of Kuwait, and what lessons can we take forward into our future? Let us remember always that allies are not always friends; victories are never permanent; and sometimes even seemingly unrelated personalities and forces can lead to world-changing events.

Our young people, especially those who wish to enter into national service, must study history and seek to possess, as the Bible says in the book of Revelation 17:9 in the Amplified Bible translation, “a mind to consider, that is packed with wisdom and intelligence … a particular mode of thinking and judging of thoughts, feelings, and purposes.”

Indeed, sometimes the world truly goes crazy and catches on fire, and some may say that 2020 is such a time. Let us study the past now, and prepare for the future!