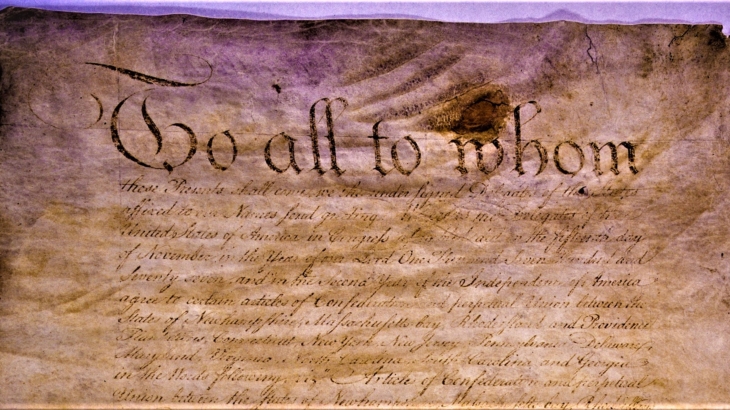

From the Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union to a United States Constitution

The Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union was our nation’s first constitution and essentially served as the basis for our government from 1777 to 1789. It was created by the thirteen original states to help them unify their war efforts against England and was the precursor to our present Constitution.

In June 1776, soon after the Second Continental Congress appointed the Committee of Five to draft the Declaration of Independence, Congress also established a committee to craft a document by which this new country would be governed. Comprised of one delegate from each colony and chaired by John Dickinson of Pennsylvania, these thirteen men presented their initial draft to Congress on July 12, 1776.

They named it the Articles of Confederation, suggesting a fairly loose coalition rather than one united entity. Although the states agreed to form a national government, they were not willing to cede any of their individual rights or powers to it.

After much debate and five different versions, the Articles were finally approved by Congress on November 15, 1777, and immediately sent to the various states for their ratification. Although official approval of the document required all thirteen states to ratify it and the thirteenth state (Maryland) did not do so until February 2, 1781, the Articles effectively guided Congress’ action from 1777 onward.

The Articles stressed the rights of the individual states more than the power of the central government. As Article II states, “Each state retains its sovereignty, freedom, and independence, and every power, jurisdiction, and right, which is not by this Confederation expressly delegated.”

Additionally, the states viewed this association as a group of co-equals and there was no consideration given for the size, wealth, or population of the various colonies. As articulated in Article V, “In determining questions in the United States in Congress Assembled, each state shall have one vote.”

Article IX entrusted several responsibilities to the Confederation Congress such as dealing with Indian nations and foreign affairs to include making treaties, declaring war, and making peace. However, the Article also required “nine states assent” to virtually anything Congress wanted to do. Given the sessions were lightly attended by the delegates, quorums were often difficult to attain which made passing any new legislation even more challenging.

Interestingly, Article XI expressly allowed for the addition of Canada to our confederation if that colony so chose. That fact indicates how precarious was England’s hold on our northern neighbor in the minds of Americans in the 1770s. Finally, as Article XIII states “the Union shall be perpetual” which meant that joining the compact was permanent and there was no recourse for leaving the Union.

The Articles of Confederation as approved created an amazingly weak central government. One might ask why the states would take the time to form a national government at all if the one they designed was powerless and ineffective. It is important to remember state sovereignty was paramount to virtually all political leaders in early America.

As the move towards independence gained traction in 1776, states codified freedoms in their own state constitutions that had been denied to them under King George and Parliament. With each state already guaranteeing liberties to all citizens, there was no need or desire to create a powerful entity at the federal level to ensure them.

This extreme focus on state’s rights is understandable when one considers how the original colonies had been established. Rather than the eastern seaboard being populated by the English all at once, the various colonies had been settled separately and independent of the others. Naturally, each colony jealously guarded its autonomy.

The inherent weakness of the federal government, and the danger that posed, became clear as the American Revolution got underway. Although its provisions authorized the central government to regulate and establish an Army, it lacked the power to enforce its decrees. While Congress could request funding and troops from the states, all money and men would only be forthcoming if the states agreed to the requests. Not surprisingly, most requests were ignored.

This lack of funding and men almost proved the undoing of the Continental Army which, of course, would have meant the end of our effort to win independence. As General George Washington wrote to George Clinton from Valley Forge in February 1778, “For some days past, there has been little less than a famine in camp.” He went on to write, “When the fore mentioned supplies are exhausted, what a terrible crisis must ensue.”

Unfortunately, funding for the army only got worse after we secured our independence. With the threat from England largely ended, the national army shrank to a skeletal force that attempted without much success to protect the western borders from Indian attack. Additionally, because of this military impotence, the United States could not compel England to abandon its forts in the Northwest Territory as called for in the Treaty of Paris.

The Articles also expressly denied Congress taxation authority. Consequently, the central government was constantly short of cash and unable to pay its bills. Congress printed more money, but this only served to devalue the currency. To make matters worse and national finances more confusing, the individual states had the right to print their own currency as well.

Another flaw was the lack of an executive branch. Although the men who presided over the Continental Congress were called “President,” they had no power, and many served in that position for less than a year. Most delegates had seen too much of King George and monarchy to be willing to entrust significant authority in one central figure.

These issues aside, the Articles of Confederation deserves some credit. For one thing, it was our first constitution, and with it we survived the American Revolution and six years beyond.

The Articles also granted the Confederation Congress the authority to establish an efficient system for expanding the new nation. Its provisions for new territories and how to settle them as seen with the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 proved to be a boon in the decades that followed.

So why should the Articles of Confederation matter to us today? Perhaps the greatest blessing of the Articles was its flaws. Our nation’s leaders were able to see and learn early on what we needed in a central government for our country to succeed.

While we feared a powerful Federal government, we realized one that was powerless would ensure our demise. The recognition that we needed to balance these two concerns led to the changes our Founding Fathers incorporated into our Constitution.

If you want to learn more about the Articles of Confederation, I suggest reading “We Have Not a Government: The Articles of Confederation and the Road to the Constitution” written by George Van Cleve. Published in 2017, it is an excellent account of the troubles resulting from the weakness of the Articles and how those troubles led to the creation of our Constitution.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of Americana Corner. Tom is a West Point graduate, and serves on the board of trustees for the American Battlefield Trust as well as the National Council for the National Park Foundation. Click Here to Like Tom’s Facebook Page, Americana Corner. Click Here to follow Tom’s Instagram Account.

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of Americana Corner. Tom is a West Point graduate, and serves on the board of trustees for the American Battlefield Trust as well as the National Council for the National Park Foundation. Click Here to Like Tom’s Facebook Page, Americana Corner. Click Here to follow Tom’s Instagram Account.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!