Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Does the United States today resemble the nation envisioned by the American Founders? Have we lived up to the political and constitutional principles they believed are so important for maintaining a free society and remaining a self-governing people? Have we as a people done a good job of preserving those principles by educating and reminding each generation on their importance? Constituting America’s 90-Day Study on “First Principles of the American Founding” should help each of us, as citizens, think about the first two questions in a more enlightened and informed way – and certainly goes far in ensuring that the third question is answered in the affirmative.

In this series of essays, written by exceptionally thoughtful thinkers, teachers and scholars, we can discern how insightful the American Founders were in recognizing and articulating the first principles upon which the nation of America was founded. From ideas identifying the basis of rights in nature rather than tradition, to constitutional principles that established a limited government, to foreign policy principles meant to promote justice with other nations, these essays allow us to glean in a more capacious way the overarching ideas that informed who we were meant to be as a people and a nation.

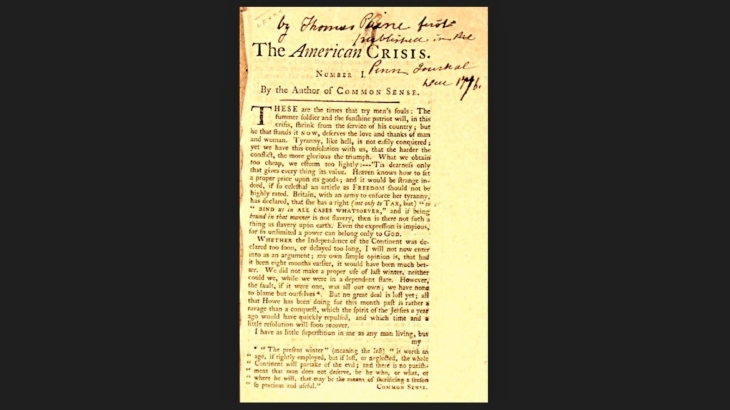

These essays reveal that Americans, and especially the Founders, had learned extensively from the careful study of history. Born of English tradition, Americans gradually came to develop their own identity – one might even say “mind,” as Thomas Jefferson called it. Separated from Great Britain and largely left alone for decades, American colonists lived in relative freedom and came to establish local governments and social institutions that complemented their understanding of rights and liberties. They frequently heard these ideas of individual liberty and limited government reinforced in their churches, newspapers, shops, and businesses. The essays in the 90-Day Study, as a whole, show the story of how Americans became one people united by common principles.

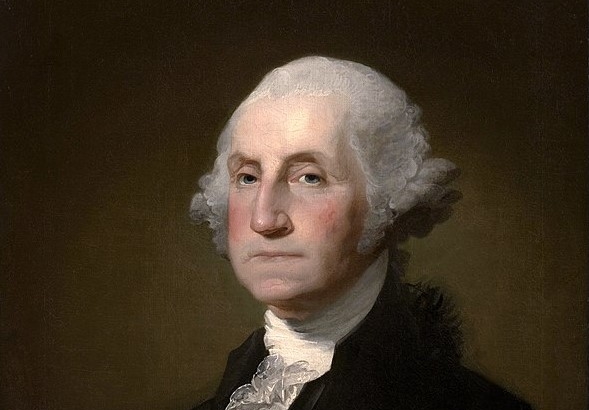

The American Revolution was, in more than one sense, a test of those principles. Should the Revolution fail, the principles of liberty and self-government might be lost forever. It was also a test in the sense that Americans found themselves in the position of having to accomplish a political separation and wage a war in accordance with the very principles they declared to be self-evidently true. Winning the war and gaining independence seemed to many, including George Washington, nothing short of miraculous. Having accomplished this, Americans next found themselves having to apply the principles of the Declaration of Independence to the creation of a government that would fulfill the demands of justice both at home and toward foreign nations. In other words, Americans had to learn how to act like a nation – and this is when Americans applied and thought even more deeply about the meaning of their founding principles.

Domestically, Americans faced the great difficulty of establishing a republic, based on consent, to replace the traditional form of monarchy that had prevailed throughout most of human history. The challenge facing the Framers of the United States Constitution was how to frame a government that was sufficiently powerful to secure the natural rights of American citizens, but that was also sufficiently checked to prevent it from abusing and violating these rights and liberties. Another great challenge was to find constitutional ways of obligating America’s government to secure American sovereignty and independence, and to respect the independence and sovereignty of other nations. The essays in this 90-Day Study reveal that, to fulfill these ends, knowledge of fundamental principles proved to be the guiding star for the Framers of the Constitution, and the standard by which American citizens could judge the justice or injustice of acts of government even after the Constitution had been ratified.

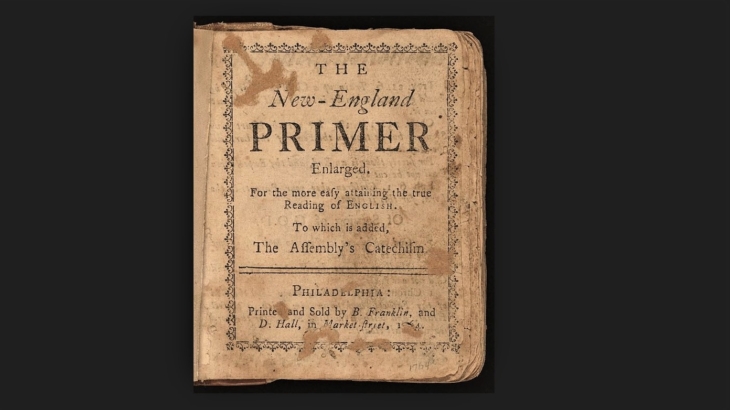

In the end, these essays bring to the fore the Founders’ view that without civic virtue, no government – not even America’s own Constitutional government – can succeed. Local political participation can never be replaced by national administration without some cost to individual liberty; and despite the best efforts of the Framers of the Constitution, civic awareness and engagement is still necessary to check laws and policies that are contrary to the principled purposes of government. All of this reinforces why the Founders believed that a proper civic education of the American people was so critical – an education that informs them of both their rights and duties. This 90-Day Study, as a whole, aims to fulfill that crucially important purpose of the American Founders.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg_trials#/media/File:Color_photograph_of_judges'_bench_at_IMT.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg_trials#/media/File:Color_photograph_of_judges'_bench_at_IMT.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/League_of_Nations#/media/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/League_of_Nations#/media/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headquarters_of_the_United_Nations#/media/File:UN_Members_Flags2.JPG

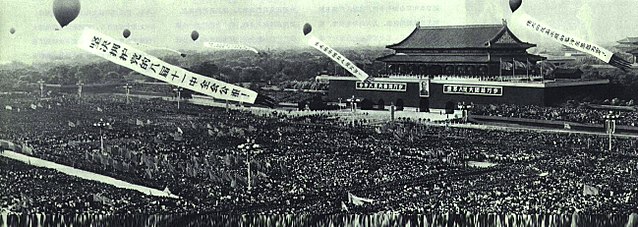

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headquarters_of_the_United_Nations#/media/File:UN_Members_Flags2.JPG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Maurits_(1567-1625),_prins_van_Oranje,_in_de_slag_bij_Nieuwpoort_(1600).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Maurits_(1567-1625),_prins_van_Oranje,_in_de_slag_bij_Nieuwpoort_(1600).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Years%27_War#/media/File:Siege_of_Namur_(1692).JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Years%27_War#/media/File:Siege_of_Namur_(1692).JPG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Diet_(Holy_Roman_Empire)#/media/File:Luther_(Wislicenus).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Diet_(Holy_Roman_Empire)#/media/File:Luther_(Wislicenus).jpg