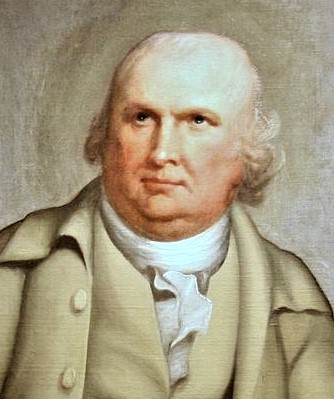

Robert Morris of Pennsylvania: Merchant, Superintendent of Finance, Agent of Marine, and Signer of the Declaration of Independence

Robert Morris, Jr., is one of only two men who signed the Declaration of Independence, the Articles of Confederation, and the Constitution of 1787. He thus was present at three critical moments in the founding of the United States. His most significant contributions to that founding occurred during the decade of turmoil framed by the first and last of these, that is, the period of the Revolutionary War and the Confederation.

Morris was of English birth, but came to Pennsylvania as a child. He inherited a substantial sum of money when his father, a tobacco merchant, died prematurely. After serving an apprenticeship with his father’s former business partner, Morris started a firm with that partner’s son. The firm became a success in the tobacco trade, marine insurance, and commerce in various merchant goods. For these reasons, Morris opposed British taxes on merchants and laws that hindered trade, especially that done with American vessels.

After the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord, Morris was selected to Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety. His efforts to secure ammunition for the Continental Army led to his appointment to Pennsylvania’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress, which met in the capital at Philadelphia. Morris was torn between opposition to the British government’s actions and his loyalty to the Crown. He sought to mediate between the radicals pressing for independence and the traditionalists seeking to negotiate continued connection with the motherland. When it came time to vote on Richard Henry Lee’s motion for independence on July 2, 1776, Morris and fellow Pennsylvania moderate John Dickinson absented themselves to allow that colony’s delegation to vote in favor. Independence having been declared, Morris went with the tide and signed the Declaration the following month.

During the Revolutionary War, the very wealthy Morris assumed two roles befitting his talents, finance and shipping. Even before independence, he served on the Committee of Trade and the Marine Committee. Once the Articles of Confederation were finally approved in 1781, he was given more formal executive offices, Superintendent of Finance, analogous to the current Secretary of the Treasury, and Agent of Marine, the former version of the Secretary of the Navy. As well, he continued his efforts to secure supplies for the Continental Army through those positions.

It was particularly in the former capacity that he excelled and later received the appellation “Financier of the Revolution.” The new country was, not to mince words, a financial basket case. To term the promissory notes of the Confederation “junk bonds” would be flattery. The British had refused to allow the creation of a domestic banking system in the colonies, in order to maintain control over the economy, thwart independence, and promote the ascendancy of London as the world’s financial center over Amsterdam. Each colony had had its separate financial relationship with London. In the colonies themselves, someone wanting credit had to obtain loans from local merchants. The country was utterly without even a rudimentary integrated banking system.

Commerce, as well, had been regulated by the British to their advantage. Restriction on colonial trade with the West Indies and with continental European countries had been a recurring source of friction in the decade before the War. Shortly before American independence was declared, Parliament in December, 1775, had passed the Prohibitory Act, which outlawed commerce even between the colonies and England. With independence, the gloves came off entirely. The British navy threw a blockade around American ports, which brought legal sea-borne trade to a standstill. American efforts to avoid this blockade through smuggling and eventual licensing of privateers were spirited, but nothing more than a nuisance to the British maritime stranglehold on American commerce.

Money itself was both scarce and overabundant. Scarce, in the form of gold and silver; overabundant in the form of paper currency. Not only British coins circulated, but also those from many other European countries, especially Spanish silver pieces-of-eight (akin to the future silver dollar) and gold doubloons. States issued a few small copper coins along with significant amounts of “bills of credit,” that is, paper scrip which depreciated in value and was at the center of much commercial speculation, economic chaos, and political intrigue over the first decade of independence.

The Confederation’s currency, the Continental Dollar, was, if anything, even more pathetic. Aside from a few pattern coins struck in 1776 mostly in base metals, the currency was issued as paper. Although historians’ research has not been able to reach a definitive conclusion, it appears that, over the course of about five years, about 200 million dollars’ worth was printed. To put this in perspective, the population of the United States at the time was about .8% of that of today. The current purchasing power of the dollar is about one-thirtieth of the value of coins then, and the value of gold was about a hundred times the current nominal value. Due to massive British counterfeiting, even more than that amount of Continental currency actually may have circulated. Congress had no domestic sources of income, because it lacked the power to tax directly. Instead, it must seek requisitions from the states. Although the states were obligated under the Articles of Confederation to pay those requisitions, their performance was unsteady and varied from state to state, especially as the financial demands of the war, the turmoil of military campaigns, and the strangulation of commerce by the British blockade took their toll on their economies.

The printing of vast amounts of currency, out of proportion with what the country could back up with hard assets, such as gold and silver, led to serious inflation. The currency depreciated to such a point that, by 1781, it ceased to be used as a medium of exchange. It did, however, gain linguistic currency through the commonly-used contemptuous aphorism, “Not worth a Continental” to signify something of no value.

Enter Robert Morris. Congress appointed him Superintendent of Finance in 1781. Attempting to ameliorate the desperate financial situation of a bankrupt country, he began to finance the Continental Army’s supplies and payroll himself through “Morris notes” backed by his own credit and resources. His efforts over the next three years, while crucial in averting political disaster, still fell short. The seriousness of the matter was underscored by several near-mutinies among elements of the officer corps of the Army: the Pennsylvania Line Mutiny of January, 1781, the McDougall delegation’s delivery to Congress in December, 1782, of an ominous petition signed by a number of general officers, and the Newburgh Conspiracy by a large contingent of Army officers in early 1783. They all showed the simmering threat to the young republic from Congress’s broken promises caused by the lack of funds to pay the military. Morris’ correspondence with some staff officers at General Washington’s headquarters revealed a desire for new ways to force Congress to compel the states to meet their financial obligations. This gave rise to unsubstantiated rumors that the military’s discontent, especially the Newburgh Conspiracy, was supported, or even instigated, by Morris and other “nationalist” members of Congress.

In other financial matters, Morris directed his efforts to create a banking system, in order to improve access to private credit and to stabilize public credit. In this matter he was assisted by his able protege, Alexander Hamilton, himself trained in business and finance before joining the military. Morris issued a “Report on Public Credit” in 1781, which proposed that Congress assume the entire war debt and repay it fully through new revenue measures and a national bank. The first part of this ambitious endeavor failed when, in 1782, Rhode Island alone refused to approve an amendment to the Articles of Confederation to give Congress the power to tax imports at 5% as a source of revenue.

However, Morris did obtain a charter from the Confederation Congress on May 26, 1781, for the Bank of North America. Modeled after the Bank of England, it began its operation as the first commercial bank in the United States in early 1782. It also took on some functions of a proto-central bank in its attempt to stabilize public credit. About one-third of the bank shares were purchased by private entities, the rest by the United States. Morris used $450,000 of silver and gold from loans to Congress by the French government and Dutch bankers to fund the government’s purchase of its bank shares. He then issued notes backed by that gold and silver for loans, including to the United States. When Congress appeared unable to repay the loans, Morris sold portions of the government’s shares to investors to raise funds. Using those funds, he repaid the bank and then issued more notes to lend to the government to meet its financial obligations.

Unfortunately, despite Morris’ energy and financial wizardry, the Confederation’s debts continued to expand, with no clear way to repay them that was constitutionally permitted and politically feasible. European lenders had reached the end of their patience. Unwilling to remain a part of this calamitous system, Morris resigned from Congress in 1784, having been preceded in exit by Hamilton for similar reasons a year earlier.

As a constitutional matter, the Bank’s charter was challenged early as beyond Congress’ limited powers under the Articles of Confederation. Morris obtained a second charter, from Pennsylvania, in 1782. That state’s legislature briefly revoked the charter in 1785, before reinstating it in 1786. With the end of the Confederation in 1788 due to the adoption of the new Constitution, the Bank’s charter under the Articles expired. It continued to operate as a state institution within Pennsylvania. Through a series of mergers and acquisitions since then, the Bank’s remains are part of Wells Fargo & Co. today. Its role as a national bank, but one supported by a much sounder constitutional and economic foundation, was recreated by the Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress in 1791 at the urging of Alexander Hamilton, and by-then, Senator Robert Morris.

In his role as official Agent of Marine, as well as in an informal capacity before then, it was Morris’ job to supervise the creation of a navy and to direct operations. Congress authorized the construction of more than a dozen warships. These were no match for the Royal Navy. They were primarily used as commerce raiders to capture British merchant ships. Almost all were sunk, scuttled, or captured by 1778. Most American naval ships were armed converted merchant vessels often owned by private individuals. The most effective raiders, favored by Morris, were privateers, which were private vessels licensed by Congress to attack British shipping. Nearly 2,000 such letters of marque were issued by Congress, which caused an estimated $66 million of losses to British shipping. Privateering was so profitable for a time that Morris and other investors built and sent out their own privateers.

After the Revolutionary War, Morris focused on private business, including the favorite investment activity of moneyed Americans, land speculation. On the political side, he was selected by Pennsylvania for its delegation to the Constitutional Convention of 1787. He presided at the opening session on May 25, where he moved to make George Washington the presiding officer. He was a nationalist in outlook and, based on his experience as Superintendent of Finance under the Confederation, wanted to assure the general government a power to tax. He favored replacing the Articles, rather than just amending them. Beyond that, he had no real philosophical commitment to the particulars of the new constitution. Not being a politician or political theorist, he had little influence on the proceedings.

With the new government in place, the Pennsylvania legislature elected Morris to the United States Senate. President Washington wanted to make Morris Secretary of the Treasury. Morris demurred and recommended Hamilton in his stead. The two were closely aligned on economic and commercial policy. Hamilton’s “First and Second Reports on the Public Credit” in 1790 reflected Morris’ own “Report” of a decade earlier respecting the assumption and funding of war debts and the creation of a national commercial bank.

Morris’ genius in financial matters did not save him from economic disaster. He overextended himself in his land speculation. His company owned millions of acres of land. The Panic of 1797, triggered by the damage to international trade and immigration caused by the Napoleonic Wars in Europe, left Morris land-rich and cash-poor. As a consequence of depreciating land values and insufficient cash to pay creditors and taxes, he spent three and a half years in debtor’s prison. The incarceration only ended in August, 1801, after Congress passed a bankruptcy law for the purpose of obtaining his release. He was adjudged bankrupt, and his then-almost inconceivable remaining debt of nearly $3 million was discharged. Still, Morris and his wife were left virtually penniless, having received just a small pension. He died in 1806.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!