Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

It is tempting to regard the American founding and the constitutional order it brought into being as relying almost exclusively on self-interest, or at best “enlightened self-interest.” We take for granted that, as James Madison observes in Federalist #51, human beings aren’t angels, and that our political order is so constructed, through institutional checks and balances, as to make ambition counteract ambition. We also find it easy to agree with Madison’s argument, in Federalist #10, that we are animated by the pursuit of our interests, which most frequently and reliably (but not exclusively) are defined in “selfish” economic terms:

Those who hold and those who are without property have ever formed distinct interests in society. Those who are creditors, and those who are debtors, fall under a like discrimination. A landed interest, a manufacturing interest, a mercantile interest, a moneyed interest, with many lesser interests, grow up of necessity in civilized nations, and divide them into different classes, actuated by different sentiments and views.

Viewed from this perspective, interest group politics might seem a sordid business, with emphasis on both its sordidness and its commercial character. Economists are comfortable disparaging most political action in terms of “rent-seeking,” i.e., using political power to redistribute the wealth generated by the market. Thus it’s not surprising that one commentator famously devoted an entire book to examining Why Americans Hate Politics.

But for a variety of reasons, this view is incomplete and short-sighted. To begin with, our founders certainly didn’t take the view that politics was venal, sordid, and basically selfish. After all, they pledged their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor to the task of establishing American independence, not a rational risk for someone out simply to maximize profit or utility. As John Adams wrote on April 26, 1777 to his wife Abigail, “Posterity! You will never know, how much it cost the present Generation, to preserve your Freedom! I hope you will make a good Use of it.” For Adams, freedom was not something to be cast away or consumed, but rather to be preserved for oneself and one’s posterity. It wasn’t understood merely as a condition of one’s immediate personal gratification, but as a cherished trust to be handed down from generation to generation.

We can look to the founding generation for examples of how to take this trust seriously. First, in the Northwest Ordinance, passed by Congress under the Articles of Confederation and then repassed by Congress under the United States Constitution, we read these words: “Religion, morality, and knowledge, being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” Schools don’t just train workers or create clever consumers; they are to engage in civic education, uniting morality (which as George Washington reminds us, is supported by religion) with knowledge for the sake of good government.

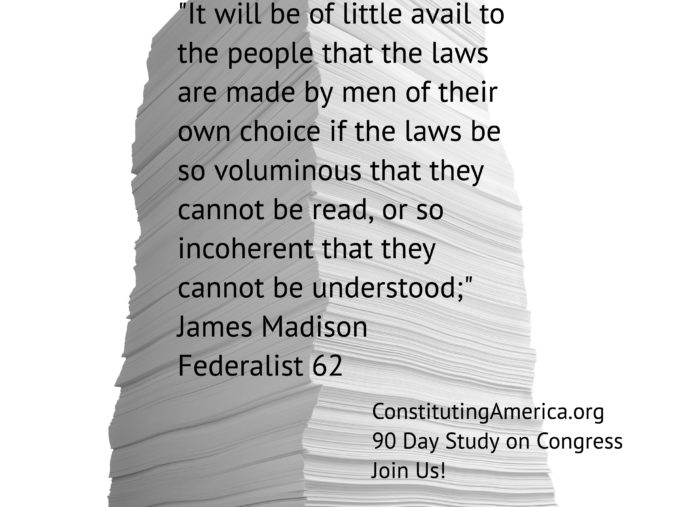

Second, in Federalist #10, immediately after describing the different interests that grow up in “civilized nations,” Madison says that the “regulation of these various and interfering interests forms the principal task of modern legislation.” This “regulation” should not consist in the dominance of one interest—majority or minority—over others, but should seek to attain “the permanent and aggregate interests of the community.” While, to be sure, “enlightened statesmen may not always be at the helm,” managing this conflict for the common good, those who represent the people should be acquainted with the diverse array of concerns and interests among their constituents. This can only happen if these representatives have the disposition to listen and the capacity to understand and if the people can engage in respectful conversation with one another and with their representatives. And then, to be effective, these representatives must be able to engage productively with their counterparts from across the country. It is entirely in line with these expectations that men like Benjamin Franklin, Benjamin Rush, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and George Washington cared deeply about the education of future generations. Our political leaders should not merely be wealthy and well-born (as the Anti-federalists feared), but rather selected for their excellence and held accountable by a vigilant and well-informed electorate.

Finally, some of the founders presciently anticipated an argument made in great detail by Alexis de Tocqueville in Democracy in America. Thomas Jefferson frequently promoted a plan of dividing Virginia into wards, modeled on the New England townships Tocqueville later celebrated. Each was to be responsible for local education and self-government. These “little republics,” as he put it in a letter to John Tyler (May 26, 1810), “would be the main strength of the great one.” While Jefferson’s plan was not formally instituted, Tocqueville found that its spirit permeated the young nation he visited:

Americans of all ages, all conditions, all minds constantly unite. Not only do they have commercial and industrial associations in which all take part, but they also have a thousand other kinds religious, moral, grave, futile, very general and very particular, immense and very small…. Everywhere that, at the head of a new undertaking you see the government in France and a great lord in England, count on it that you will perceive an association in the United States.

Arguments and examples could be multiplied from Tocqueville’s great book, some pertaining to participation in local politics, others to the creation of the variety of associations I just mentioned, but Tocqueville’s main point echoes that made by those long-time rivals and friends, Adams and Jefferson: engaging with one another is the republican and democratic substitute for and prophylactic against both aristocratic and governmental paternalism.

Joseph M. Knippenberg is Professor of Politics at Oglethorpe University in Brookhaven, GA, where he has taught since 1985.

Joseph M. Knippenberg is Professor of Politics at Oglethorpe University in Brookhaven, GA, where he has taught since 1985.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.