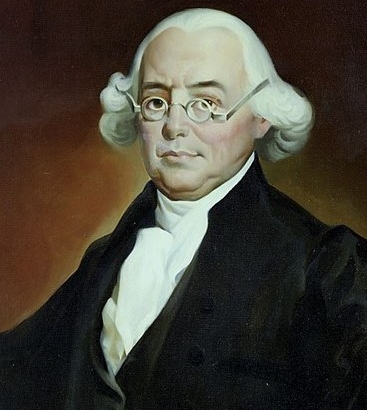

James Wilson of Pennsylvania: Land Speculator, Lawyer, Second Continental Congress Delegate, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, and Declaration of Independence Signer

James Wilson was one of the most intellectually gifted Americans of his time. His cumulative influence on pre-Revolutionary War political consciousness, formation of the governments under the Constitution of 1787 and Pennsylvania’s constitution of 1790, and early Supreme Court jurisprudence likely is second-to-none. Along the way, he amassed a respectable fortune, and took his place as a leading member of the political and economic elite that played such a critical role in the events leading to American independence. That said, he was not immune to the “slings and arrows of outrageous fortune,” in the words of the Bard, but, for the most part, he did not suffer them in the mind. Rather, more often, he chose “to take arms [sometimes literally]…and, by opposing, end them.”

Wilson moved to Philadelphia from his native Scotland in 1766, at age 24. Prior to emigrating, he was educated at Scottish universities. There, he was influenced by the ideas of Scottish Enlightenment thinkers, such as David Hume and Adam Smith. Their ruminations about human nature, the concept of knowledge, and the ethical basis of political rule shaped Wilson’s intellectual ideas which he made concrete in later political actions and judicial opinions.

It appears that Smith’s influence was more constructive than Hume’s. The latter denied the essential existence of such concepts as virtue and vice. Hume instead characterized them as artificial constructs or mere opinion. Wilson was critical of Hume’s patent skepticism, deeming it flawed and derogatory of what Wilson saw as the moral sensibilities integral to human nature. He considered Hume’s skepticism inconsistent with what he viewed as the ethical basis of the political commonwealth, that is, consent of the governed. As he wrote later, “All men are, by nature equal and free: no one has a right to any authority over another without his consent: all lawful government is founded on the consent of those who are subject to it.” However, Wilson also believed, along with John Adams and many other republicans of the time, that such consent could only be given by a virtuous people. In short, Wilson’s democratic vision was elitist in practice. The governed whose consent mattered were the propertied classes. The others might register their consent, but only under the watchful eyes of their virtuous betters in society.

After arriving in Pennsylvania, he studied law under John Dickinson, another member of the emerging political elite. While so occupied, he also lectured, mostly on English literature, at the College of Philadelphia, site of the first medical school in North America. He had arrived at an institution that was connected to an astonishing number of American founders. Despite its relatively recent founding in 1755, it counted 21 members of the Continental Congress as graduates; nine signers of the Declaration of Independence were alumni or trustees; five signers of the Constitution held degrees from the College, and another five were among its trustees.

There, Wilson successfully petitioned to receive an honorary Master’s degree, to remedy his failure to complete his studies for a formal degree at the Scottish universities. His scholarly association with the College of Philadelphia continued the rest of his life, including after its merger into the University of Pennsylvania in 1791. At that time, Wilson took on a lectureship in law for a couple of years, only the second such position established in the United States, after the Chair in Law and Police held by George Wythe at the College of William and Mary. The University of Pennsylvania traces its eventual law school to Wilson’s position.

Wilson practiced law in Reading, Pennsylvania. His talent and connections quickly produced financial security. He turned his attention to politics amid the stirrings of conflict with the British government. In 1768, he wrote, “Considerations on the Nature and Extent of the Legislative Authority of the British Parliament.” In this pamphlet, Wilson denied the authority of Parliament to tax the American colonists because of the latters’ lack of representation in that body. Perhaps because it was too early to mount a direct constitutional challenge to the authority of Parliament to govern, this seminal work was not published until 1774. Despite his negation of Parliamentary authority, Wilson did not advocate sundering all ties with the mother country. Rather, he emphasized the connection between England and her colonies through the person of King George. Wilson’s union cemented by a pledge of allegiance to the king was a rudimentary plan for the type of dominion system that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson also proposed in separate missives that same year. In an ironic postscript, the British ministry offered, too late, a similar structure as a way to end the war in 1778. It was a system the British a century later instituted for other parts of their empire.

In 1774, Wilson was elected to the local revolutionary Committee of Correspondence. When the Second Continental Congress was called in 1775, Wilson was elected to the Pennsylvania delegation. With the Adamses—John and Sam—, Jefferson, the Lees of Virginia— Richard Henry and Francis—, and Christopher Gadsden—the “Sam Adams of the South” and designer of the Gadsden Flag—Wilson was among the most passionate pro-independence voices as that Congress deliberated.

Then occurred an odd turn of events. When Richard Henry Lee’s motion for independence came up for debate on June 7, 1776, consideration had to be postponed because Pennsylvania, along with four other colonies, was not prepared to vote in favor. John Dickinson, Wilson’s close friend and law teacher, was part of the peace faction. Did that influence Wilson’s vote? Was Wilson really a pro-independence radical, as his writings and soaring rhetoric in Congress indicated? Or was he an elite conservative reluctantly floating along with the tide of opinion among others of his class? Wilson and others in his delegation claimed that they merely wanted clearer instructions from their colony’s provincial congress. In a preliminary vote within the Pennsylvania delegation on July 1, 1776, Wilson broke with Dickinson and voted for independence. When Congress voted on Lee’s motion the next day, Dickinson and Robert Morris stayed away. Wilson, Benjamin Franklin, and John Morton then cast Pennsylvania’s vote in favor of the motion and independence.

During the Revolutionary War, Wilson divided his time between Congress and opposing Pennsylvania’s new constitution. He also returned to private law practice and served on the board of directors of the Bank of North America. That bank was the brainchild of fellow-Pennsylvanian Robert Morris, another personal friend with whom Wilson also worked closely on the financial matters of the United States.

Wilson continued his life-long practice of land speculation, the vocation of some among the American elite, and the avocation of most others, elite or not-so-elite. The country was land-rich and people-poor. Investors gambled that, after peace was restored, the British pro-Indian and anti-settlement policy of the Proclamation of 1763, which had prohibited American settlement of the interior, would be overturned. Western lands finally would be opened to immigrants. Wilson, along with Robert Morris and many other prominent Americans and some foreigners, had organized the largest of the land companies, the Illinois-Wabash Company, even before the war. Wilson eventually became its head and largest investor. The intrigue among the Company, politicians in various states, delegates to Congress, and agents of foreign governments to gain access to large tracts of trans-Appalachian lands presents a fascinating tale of its own.

The Illinois-Wabash Company was not Wilson’s only venture in land speculation. He co-founded another company and also purchased rights to large tracts individually or in partnership with others. It has been estimated that, directly or through investment entities, Wilson had interests in well over a million acres of Western land. Much of this land bounty was financed through debt. Creditors want cash payment, and highly-leveraged debtors are particularly vulnerable to economic contractions. Land values drop as land goes unsold, and cash in the form of gold and silver specie becomes scarce. Bank notes no longer trade at par, reflecting the financial instability of their issuers. Like his business associate and political ally Robert Morris, Wilson was hit hard by the Panic of 1796-7. He was briefly incarcerated twice in debtor’s prison, even after fleeing Pennsylvania for North Carolina to avoid his creditors. More astounding even was that these events occurred while he was on the U.S. Supreme Court and performing his circuit riding duties.

One sling of outrageous fortune against which Wilson literally took arms occurred on October 4, 1779. After the British abandoned Philadelphia, the revolutionary government undertook to exile Loyalists and seize their property. As John Adams had done for the British soldiers accused of murder in the Boston Massacre in 1770, Wilson successfully took up the unpopular cause of defending 23 of the Loyalists. The public response to Wilson’s admirable legal ethics was more militant than what Adams had experienced. Incited by the speeches of Pennsylvania’s radical anti-Loyalist president, Joseph Reed, a drunken mob attacked Wilson and 35 other prominent citizens of Philadelphia. The mob’s quarry managed to barricade themselves in Wilson’s house and shot back. In the ensuing melee, one man inside the house was killed. When the mob tried to breach the back entrance of the house, the attackers were beaten back in hand-to-hand combat. The fighting continued, with the mob using a cannon to fire at the house. At that point, a detachment of cavalry appeared, led by the same Joseph Reed, and dispersed the mob. It is estimated that five of the mob were killed and nearly a score wounded. Members of the mob were arrested, but no prosecutions were launched, allegedly to calm the situation. Eventually, all were pardoned by Reed.

The Fort Wilson Riot, as it became known colloquially, had more complicated origins and produced more profound changes than one can address in detail in an essay about Wilson. It arose from difficult economic circumstances and rising prices due to food shortages. The lower classes were particularly hard hit, and popular resentment simmered for months, punctuated by gatherings and publications which none-too-subtly threatened upheaval. During that volatile time, Wilson was accused of “engrossing,” that is, hoarding goods with the intent to drive up prices. This may have made him an even more likely target for the mob’s wrath than having defended Loyalists.

As well, the friction between the lower classes and the merchant bourgeoisie was manifested in competing political factions, the Constitutionalists and the Republicans. The former supported the radically democratic Pennsylvania constitution of 1776, which placed power in a unicameral legislature closely monitored through frequent elections. They stressed the need for sacrifice for the common good, done on a voluntary basis or by government force. The latter opposed that charter as the cause of ineffective government and destructive policies which threatened property rights. In the end, the two competing visions of republicanism settled their political conflict during the riot. The mob had violated an unwritten rule of protest, and popular opinion shifted against the Constitutionalists. Wilson’s Republicans had won. They would determine the subsequent political direction of the state, which became the critical factor in Pennsylvania’s struggle to approve the proposed U.S. Constitution in the fall of 1787. The shift in political fortunes culminated in 1790 in a significantly different constitution, one of more balanced powers controlled by the political elite and containing explicit protections of property rights.

Perhaps Wilson’s greatest contribution to America’s founding was his participation in the constitutional convention in Philadelphia in May, 1787. He became one of only six to sign both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, the others being George Clymer, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Morris, George Read, and Roger Sherman.

One of the most accomplished lawyers in the country, John Rutledge of South Carolina, future Supreme Court justice and, briefly, the Court’s chief justice, stayed at Wilson’s home during this time. The historian Forrest McDonald describes a plan by Rutledge and Wilson to “manage” the convention. Apparently, Wilson made similar plans with James Madison, Robert Morris, and Gouverneur Morris (no relation). Rutledge, in turn, was scheming with others. To complete the intrigue, Wilson and Rutledge kept their side discussions secret from each other. The plan seemed to bear fruit when Wilson and Rutledge were appointed to the Committee of Detail, charged with writing the substantive provisions of the Constitution from the delegates’ positions manifested in the votes of the state delegations. Considering the committee’s final product, however, their success appears to have been less than spectacular. It was not for lack of trying, however. Wilson spoke 165 times at the convention, more than anyone other than Gouverneur Morris.

Like his fellow connivers, Wilson took a very strong “nationalist” position in the convention. He was instrumental in the creation of the executive branch. Reacting against the weakness of the multiple executive structure of the Pennsylvania executive council model and the lack of an effective balance of power among the branches of government under his state’s constitution, he, like Alexander Hamilton, believed a unitary executive to be essential. The necessary “energy, dispatch, and responsibility to the office” would be assured best if a single person were in charge of the executive authority. As well, such a person would be positioned to blunt the self-interest of political factions which are endemic to legislatures. Wilson objected to the original proposal to have the president elected by the whole Congress or by the Senate alone. Instead, he proposed, the president should be elected by the people. Very few delegates had a taste for such unbridled democracy. Wilson then fell back to his second line of argument, that the president be selected by presidential electors chosen by the people of the states, but with the states divided into districts proportioned by population, like today’s congressional districts. This, too, was defeated by eight states to two. The matter was tabled for weeks. In the end, the current system, one that dilutes majoritarian control and favors the influence of states in their corporate capacity, prevailed.

An explanation of the term “nationalist.” As used herein, it has the classic meaning associated with the concept as it relates to the period of the founding of the United States and subsequent decades. It describes those who identified more with the new “nation,” i.e. the United States, than with the individual colonies, soon to become states, of their birth. Generalizations are, by definition, imprecise. Still, the most ardent American nationalists of the time were those who, like Wilson, Robert Morris, and Hamilton, were born abroad; those who, like Rutledge and Dickinson, had traveled or otherwise spent considerable time in Europe; and those who had significant business connections abroad. They also tended to be younger. The difference between these outlooks was less significant for the process of separating from Britain, than it was for the controversies over forming a “national” government and an identity of the “United States” through the Articles of Confederation and, subsequently, the Constitution of 1787. The nationalists sought to amend and, later, to abandon the Articles. As to the Constitution, the nationalists at the Philadelphia convention supported a stronger central government and, on the whole, more “democratic” components for that government than their opponents did. They also generally opposed a bill of rights as ostentatious ideological frippery. In the struggle over the states’ approval of the Constitution, they styled themselves as “Federalists” as a political maneuver and characterized their opponents as “Anti-Federalists.” After the Constitution was approved, most of them associated with Hamilton’s policies and the Federalist Party. In the sectionalist frictions before the Civil War, they were the “Unionists.” Regrettably, like other words in our hypersensitive culture, the term has been ideologically corrupted recently, so that its obvious meaning has become slanted. Paradoxically, even as the central government becomes powerful beyond the wildest charges of the Constitution’s early critics, the very concept of the United States as a “nation” is today under attack.

In the long wrangling over the structure of Congress, Wilson urged proportional representation, as he had done unsuccessfully a decade earlier in the debate over the Articles of Confederation. He also supported direct election of Congress by the people. In light of his moderate democratic faith in the consent of the governed, and coming as he did from a populous state, his position is hardly surprising. That noted, he favored a bicameral legislature with an upper chamber that would restrain the more numerous lower chamber and its tendency towards radical policies. The insecurity of property rights that resulted from the policies of the Constitutionalist-dominated unicameral Pennsylvania legislature had alarmed Wilson. Wilson adhered to his support for proportional representation in the Senate and direct popular election. Like his fellow large-state delegates Madison and Hamilton, eventually he resigned himself to the state-equality basis of the Senate under Roger Sherman’s Connecticut compromise and to election of that body by the state legislatures. He also supported the three-fifths clause of counting slaves for the purpose of apportionment of representatives. The purpose of that clause, first presented in 1783 as a proposed amendment to the Articles of Confederation, originally was part of a formula to assess taxes on the states based on population rather than property value. That purpose is also reflected in Article I of the Constitution.

During the debate in the Pennsylvania convention over the adoption of the Constitution, Wilson delivered his famous Speech in the State House Yard, a precursor to many arguments developed more fully in The Federalist. Wilson systematically addressed the claims of the Constitution’s critics. He defended his opposition to a Bill of Rights, declaring such a document to be superfluous and, indeed, inconsistent with a charter for a federal government of only delegated and enumerated powers. Copies of the speech were circulated widely by the Constitution’s supporters.

There were those, like Richard Henry Lee of Virginia, who claimed that the drafting convention in Philadelphia had gone beyond its mandate to propose only amendments to the Articles of Confederation and that, as a consequence, the proposed Constitution was revolutionary. Wilson drew on his philosophical roots to declare that “the people may change the constitutions whenever and however they please. This is a right of which no positive institution can ever deprive them.” This notion of popular constitutional change outside the formal amendment method set out in Article V of the Constitution was a self-evident truth to many Americans at the time. It has become much more controversial, as Americans have moved from the revolutionary ethos of the 1780s and a robust commitment to popular sovereignty to today’s more pliant population governed by an increasingly distant and unaccountable elite.

Wilson next turned his attention to the adoption of a new state constitution in Pennsylvania. At the same time, he sought the chief justiceship of the United States Supreme Court. Although that office went to John Jay of New York, President Washington appointed Wilson to be an associate justice. In that capacity, he participated in several significant early cases. As expected, he consistently took a nationalistic position. Thus, in 1793 in Chisholm v. Georgia, he joined the majority of justices in holding that the federal courts could summon states as defendants in actions brought by citizens of other states and to adjudicate those states’ obligations without their consent. Wilson reasoned that the Constitution was the product of the sovereignty of the people of the United States. This sovereignty, exercised for purposes of Union, had subordinated the states to suits in federal court as defined in Article III. The decision ran contrary to the long-established common law doctrine of state sovereign immunity. Swift and hostile political reaction in Georgia and Congress culminated in the adoption of the Eleventh Amendment to overturn Chisholm.

Wilson joined two other nationalistic decisions. One was the unpopular Ware v. Hylton in 1796, which upheld the rights of British creditors to collect fully debts owed to them. Those rights were guaranteed under the Paris Treaty that ended the Revolutionary War, but conflicted with a Virginia law that sought to limit those rights. Like his fellow-justices, Wilson applied the Supremacy Clause to strike down the state law. But he also recognized the binding nature of the law of nations, which had devolved to the United States on independence. The other was Hylton v. U.S. the same year, which upheld the constitutionality of the federal Carriage Tax Act. The case was an early exercise of the power of constitutional review by the Court over acts of Congress and a precursor to Marbury v. Madison. That power was one which Wilson had strenuously urged in the constitutional convention nine years earlier in support of a strong federal judiciary.

Depressed about his precarious economic situation and worn out from the rigors of circuit-riding duties as a Supreme Court justice, Wilson died from a stroke in 1798.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!