The Five Principles That Render the American Republic More Stable

In the last essay, I attempted to show how the framers rejected ancient political thought. In this essay, I will try to show what guided the framers of our Constitution. In Federalist 1, Publius made the bold claim that:

“it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

Publius implied that no past regime had created the circumstances for reasonable lawmaking or political stability. Past regimes lacked liberty, but they also lacked institutional arrangements to foster reflection and cooperation in law making, and thus were ruled by the force of one or the accidents of the many. Publius envisioned that America would create the opportunity for freedom and stability because of the regime’s dedication to liberty and natural rights, reliance on the people, and structure to combat the abuse of power.

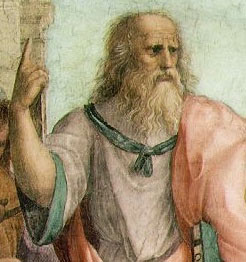

In Federalist 9, Publius revealed what regimes governed by “accident and force” look like in practice: he claimed that “The petty republics of Greece and Italy… were kept in a state of perpetual vibration between the extremes of anarchy and tyranny.” Because no regime had provided a stable foundation for “reflection and choice,” the ancient regimes were led by the force of tyrants, or the anarchy typical of pure democracies. But what did the past regimes lack that made them unstable? Publius argued that they lacked a proper constitution that assured a “firm union.”

Publius argued that various principles unavailable to the ancients allowed the framers of our Constitution to check tyranny and prohibit anarchy. In Federalist 9, he argued that the vibration between the extremes of anarchy and tyranny might give the opponents of liberty just cause to “abandon that species of government as indefensible.” However, Publius argued that “The science of politics, however, like most other sciences, has received great improvement. The efficacy of various principles is now well understood, which were either not known at all, or imperfectly known to the ancients.” He argued that five principles rendered the American republic more stable than ancient constitutions. According to Publius, the following improvements are “means… by which the excellences of republican government may be retained and its imperfections lessened or avoided”:

- “The regular distribution of power into distinct departments.”

- “The introduction of legislative checks and balances.”

- “The institution of courts composed of justices holding their offices during good behavior.”

- “The representation of the people in the legislature by deputies of their own election.”

- “The enlargement of the orbit within which such systems are to revolve, either in respect to the dimensions of a single State or to the consolidation of several smaller States into one great Confederacy.”

The last of the five improvements was the most novel, but also the most criticized. For example, both Anti-Federalists, Cato and Brutus, argued that such an enlarged sphere made “consolidation” likely, and thus endangered liberty. Montesquieu, the thinker upon whom many of the founders’ relied, argued that free government could only exist in small republics. Additionally, the free regimes of the ancient world were much smaller than the United States, and when they expanded, they became corrupt and liberty was endangered.

In Federalist 10, Publius gave his most robust defense of the “enlarged sphere.” In that paper, he considered an enlarged sphere to be the means by which the union may “break and control the violence of faction.” He argued that there are two means for dealing with the problem of faction: you may either remove the causes, or control the effects. However, the former cure– removing the causes– is worse than the disease because it would require that one remove liberty because “liberty is to faction what air is to fire.” Publius argued that two things will follow from an enlarged sphere, both of which combat faction: first, enlarging the sphere multiplies the number of factions which makes it more difficult for one faction to become a majority, and second, if the country covers a larger tract of land, it will be more difficult for a faction to “concert and carry out its schemes of oppression.”

However, Publius did not explain the most prolific difference between the American Constitution and ancient constitutions until Federalist 51. In Federalist 51, Publius argued that the constitutional form makes possible an extensive republic while also providing checks upon the abuse of power. He argued that the Constitution created an “interior structure” which made the branches “by their mutual relations… the means of keeping each other in their proper places.” In Federalist 47, Publius established that the departments of power were “distributed and blended.” The distribution of powers into separate branches, he argued, is essential to ensure accountability and prohibit the abuse of power. In fact, he argued that the very definition of tyranny is “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self appointed, or elective.”

Even before the Constitutional Convention, Madison noted that giving the government sufficient power while ensuring that power was not used to abuse rights was the “great desideratum” (Latin, meaning “great thing desired”). Publius argued that the next and most important task after dividing power was to provide some “practical security” to combat consolidation over time. In Federalist 48-50, he sought the means whereby the distribution of power into separate branches could be maintained. In Federalist 51, he revealed the practical security: the “interior structure” of the Constitution creates ambitious branches which counteract one another, and thereby limit the exercise of federal power.

Ultimately, Publius argued that in order to preserve liberty, each department must have “a will of its own” and each department should have “as little agency as possible in the appointment of the members of others”; additionally, each officer, in each branch, must have the “necessary constitutional means” and the “personal motives to resist encroachments from the others.” In other words, not only must the branches be separate, but the members of each branch must defend the rightful power of the branch to which he belongs. Publius envisioned a system in which each officer identified his own power with that of his branch, and became jealous of usurpation. He argued that the result is that “ambition” will counteract “ambition,” and each branch will check the others in the use of power. The result is that tyranny, consolidation, and the abuse of power is less likely, and the preservation of natural rights is more likely.

But in order to make each branch ambitious, each officer must be ambitious, and that requires that “the interest of the man must be connected to the constitutional rights of the place.” In order for this to occur, the officer must understand that whatever good he may do, or whatever glory he may harvest, ultimately, he requires that the branch to which he belongs maintains its Constitutional strength. Publius argues that such a system reinforces the separation of power. Paradoxically, the solution to the abuse of power is to make each branch ambitiously use its Constitutional powers to limit the abuse of power by other branches.

In our Constitution, therefore, there are a variety of institutional checks that keep the branches in their proper places. I will list a few of those checks inherent in the interior structure of our government. Publius remarks that the legislature is the most powerful branch so it is in need of extensive checks. He remarks that the legislature is an “impetuous vortex” swallowing the power of other branches. Therefore, our Constitution weakens the legislature by dividing its power between two houses and rendering each house different in mode of election and principle of representation. Additionally, the executive department has veto power over legislation. On the other hand, the Senate has the authority to declare war, so the president cannot determine foreign policy alone. The legislature is mixed with the executive and judicial departments when it comes to appointing justices of the Supreme Court, as the Senate must approve the president’s appointments to the Supreme Court. Additionally, the Vice President casts a tie-breaking vote in the Senate. The judiciary checks the legislature by considering the constitutionality of its laws. And finally, the states check the federal government because sovereignty is divided between the states and the federal government. Publius argues that this creates a “dual security” for the rights of the people.

The idea of blending power to control power, and rendering each branch sufficiently ambitious in order to combat tyranny and centralization, was an entirely new theory about how to control power. Institutionalizing this new theory made our Constitution completely novel in political science. Although the framers rejected the popular theory that a strict division of power was necessary to ensure the separation of powers, they did so after careful consideration of ancient history. For example, In Federalist 47, Publius argues that no state embraced a strict separation of power in its constitution, nor did the British government. Although almost all other regimes were forced by necessity to blend power, the American Constitution was the first to utilize the principle of blending power to ensure that power remained limited.

Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of The Center for Liberty and Learning at the Founders Classical Academy of Lewisville, Texas. Mr. Postell graduated from Ashland University with undergraduate degrees in Politics and English. He earned his master’s degree in Political Thought from the University of Dallas and is working on his dissertation to complete his Ph.D. Mr. Postell is writing a book on Henry Clay and legislative statesmanship, a subject about which he frequently writes and publishes. He has also conducted studies for Ballotpedia and has frequently contributed to Law and Liberty and Constituting America. At Founders Classical Academy he teaches courses on Government and Economics, and has taught courses on American Literature and Rhetoric.

Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of The Center for Liberty and Learning at the Founders Classical Academy of Lewisville, Texas. Mr. Postell graduated from Ashland University with undergraduate degrees in Politics and English. He earned his master’s degree in Political Thought from the University of Dallas and is working on his dissertation to complete his Ph.D. Mr. Postell is writing a book on Henry Clay and legislative statesmanship, a subject about which he frequently writes and publishes. He has also conducted studies for Ballotpedia and has frequently contributed to Law and Liberty and Constituting America. At Founders Classical Academy he teaches courses on Government and Economics, and has taught courses on American Literature and Rhetoric.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!