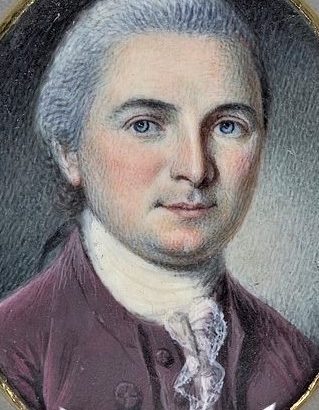

George Walton of Georgia: Lawyer, Second Continental Congress Delegate, Council of Safety Member, State Supreme Court Chief Justice, Governor, and Declaration of Independence Signer

George Walton was one of the most fascinating, but puzzling signers of the Declaration of Independence. His life and career included great triumphs and defeats, as well as a number of changes in political course that were thought by some to be rank opportunism. Others believed those choices were principled. He rose to great heights of political and governmental office, but also endured censure and disappointment, losing offices and missing opportunities for greater esteem. He died in relatively modest circumstance after serving as a senator, governor, judge, and militia officer in service to Georgia and his country.

George Walton was born in Virginia sometime between 1740 and 1750. The exact date is not known.[1] Walton’s father had died before his birth, and his mother died a few years later, so Walton was taken in by his father’s brother, who was also named George Walton. The elder Walton was not a poor man, but he had thirteen children of his own to raise, as well as those of his brother. When he was fifteen, the younger Walton was apprenticed as a carpenter, where he learned that trade. He was released from his apprenticeship while still a teenager, when he moved with an older brother to Savannah, Georgia. There, he became a clerk in an attorney’s office, and began to learn the law while on the job. By 1775, Walton had not only become a practicing attorney, but had also become one of the most sought-out and prosperous lawyers in Savannah. As his professional success grew, Walton became involved with the young Whigs opposing British rule in America.[2]

There were multiple factions jockeying for influence in Georgia’s colonial politics at the time. Some Loyalists wished to remain a British colony. The Whigs wished to separate, but they were internally divided between more radical and more conservative factions, which were concentrated in different parishes. Walton had relatives who had settled in western Georgia, but he was also connected to more conservative politicians along the Atlantic coast. Walton was elected to the provincial congress in July of 1775 and chosen for the Council of Safety in December. He also became a high-ranking officer in the Georgia militia, where he became a close follower of Colonel Lachlan McIntosh. Walton was chosen as one of five delegates to the second Continental Congress, but he was one of only three to attend the proceedings and vote on independence. Walton was the last of the three to arrive in Philadelphia, so he missed some of the debate over the motion to break free from Britain. He did arrive in time to hear John Adams’ summation of the arguments for independence. Years later, Walton wrote to Adams telling him that “Since the first day of July, 1776, my conduct, in every station in life, has corresponded with the result of that great question which you so ably and faithfully developed on that day.”[3] Walton remained an enthusiastic Adams supporter for the rest of his life.

Walton served four one-year terms in the Continental Congress, although the terms were not consecutive. Walton spent much of his time in Congress convincing other representatives of the importance of Georgia in the war effort asking for assistance. In late 1777, Walton returned to Savannah and his law practice. Walton married Dorothy Camber, who was said to be in her teens at the time. They had two sons together. Walton soon returned to public office by serving in the General Assembly. He also volunteered in November, 1778, to serve in the militia to repel a British invasion from Florida. In December, the British landed on the Georgia coast to attack Savannah. Walton ordered his militia unit to stop British troops advancing through a swamp. His troops were unable to hold their position and quickly retreated. Walton was left in the field, badly wounded by a bullet wound in his thigh and a fall from his horse. He spent the next ten months as a prisoner of war.[4]

After his release, Walton began a political transformation that perplexed many historians and at times infuriated some of his contemporaries. Over the next few years, Walton was named to a number of public offices: governor, member of the U.S. House of Representatives, state supreme court chief justice, and United States Senator. Before and during the revolutionary war, Walton had been a political ally of Lachlan McIntosh and a virulent critic of Button Gwinnett, who had joined Walton and Lyman Hall in Philadelphia as Georgia’s representatives to the Second Continental Congress. Walton was even censured for his support of a duel in which McIntosh killed Gwinnett. But after his release by the British in a prisoner exchange, Walton began to re-align himself politically with the factions that he had previously opposed. He turned away from McIntosh and fell in with the more radical faction that Gwinnett had led before his death.[5] Walton allegedly forged a letter ostensibly penned by the speaker of the Georgia house of representatives which urged the removal of McIntosh as commander of Georgia’s military forces. After the speaker reported that he had not signed the damaging letter, Congress repudiated its dismissal and restored McIntosh to his position. Later, the son of Lachlan McIntosh, Captain William McIntosh, reportedly horsewhipped Walton, a crime that led to his court-martial.[6]

Whether this was a strategic, politically opportunistic decision or a principled change of heart is not clear, but there is no doubt that many of Walton’s contemporaries believed that he had betrayed his former allies. Nonetheless, despite accusations of dishonesty and betrayal, Walton continued to be elected or nominated for public offices. Finally, after serving part of a U.S. Senate term to fill a vacancy, Walton failed to be re-elected in 1795.[7]

Earlier, in 1787, Walton was asked to attend the federal constitutional convention as a delegate from Georgia, but he declined so he could attend to matters of state. In 1789, Walton was named as a delegate to the convention to craft Georgia’s second state constitution.[8] That convention produced a document quite similar in form to the new federal constitution, with a separation of powers and a bicameral legislature.[9] After the constitutional convention, Walton was elected a second time as governor. During his time in office, the state capital was moved to Augusta, where Walton and many of his relatives had settled. Walton spent much of his time in negotiation with Indian tribes, seeking the ceding of lands to the state. Soon Walton was embroiled in two land sale scandals, one involving the “pine barren speculation” of south-central Georgia, the other, larger scandal involving the Yazoo land sales of territory making up present-day Alabama and Mississippi. Walton approved the Yazoo land sales that had begun under Governor George Mathews and which involved bribery within the state legislature. When the scandal came to light, the Georgia General Assembly enacted a law canceling and revoking the land sales that had already been completed. This led to a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision, Fletcher v. Peck, in which the court ruled, for the first time, that a state law violated the federal constitution. Specifically, the court ruled that the Georgia law violated the prohibition of the impairment of the obligation of contracts in Article 1, Section 9, Clause 1.[10]

Unlike most men of property and influence in Georgia, Walton did not own slaves. There is little record of his public views on slavery, but it is known that shortly after leaving the governor’s mansion, Walton spoke out against what he called “barbarian” treatment of members of an African-American Baptist congregation in Yamacraw, Georgia, in 1790. When the congregation first began to hold services, local whites imprisoned some of the church-goers and whipped about fifty members of the assembly. After Walton spoke out against this outrage, a state court ordered the release of the prisoners and declared that religious services could continue.[11]

In his last years, Walton lived somewhat quietly in a cottage outside of Augusta that was located on confiscated Tory land. He never completely left public life, serving as a superior court judge and speaking out on matters of public concern that received his attention. He became an enthusiastic booster supporting the economic development of Augusta. He was a founder of Richmond Academy and tried unsuccessfully to have Franklin College, the predecessor of the University of Georgia, located in Augusta. His last years were difficult. He had never completely recovered from his wounds incurred in the revolution and he suffered many illnesses in his final years.[12] He was not well off financially. Walton died in February of 1804, only two months after the death of his oldest son.[13]

George Walton’s reputation was marred by scandal that might have broken many politicians. But Walton continually returned to power after losing office and influence. His resolve to return again and again to the political fray displayed his commitment to the building of a new nation. One of the youngest signers of the Declaration of Independence, George Walton was certainly a skilled statesman who sacrificed much in service to his country and his state of Georgia.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also the chair of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also the chair of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

[1] https://www.dsdi1776.com/george-walton/

[2] Bridges, Edwin C. “George Walton,” in Georgia’s Signers and the Declaration of Independence, by Edwin C. Bridges, Harvey H. Jackson, Kenneth H. Thomas, Jr. and James Harvey Young. Cherokee Publishing Company, 1981.

[3] Bridges, op cit., page 64.

[4] Bridges, op cit.

[5] Bridges, op cit.

[6] Daughters of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. https://www.dsdi1776.com/george-walton/

[7] Daughters of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. ibid .

[8] Bridges, op cit.

[9] Hill, Melvin B., Jr., and Hill, Laverne Williamson Hill. “Georgia: Tectonic Plates Shifting.” In George E. Connor and Christopher W. Hammons (editors). The Constitutionalism of American States. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 2008.

[10] 10 U.S. 87 (1810).

[11] Whitescarver, Keith. 1993. “Creating Citizens for the Republic: Education in Georgia, 1776-1810.” Journal of the Early Republic 13 (4): 468.

[12] Daughters of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence. https://www.dsdi1776.com/george-walton/

[13] Bridges, op cit.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!