How the Flaws in Classical Governance Informed Debates Over the American Constitution

In his play, The Tempest, William Shakespeare wrote, “What’s past is prologue.” Building on this idea, in 1905, philosopher George Santayana wrote, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

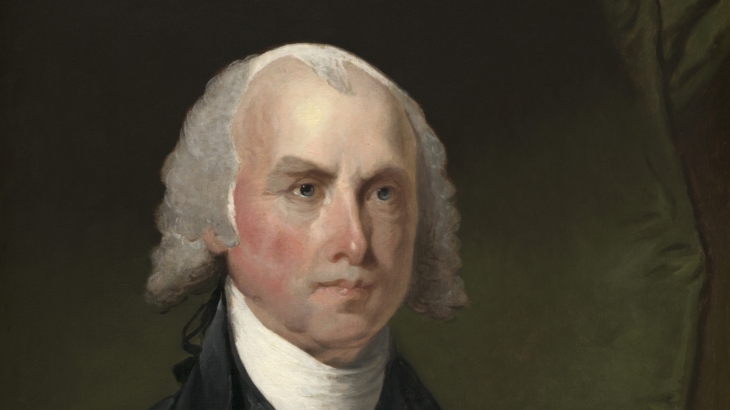

Our founders were acutely aware of this concept—even if they were unfamiliar with Shakespeare or preceded Santayana by more than a century. Firmly grounded in both the history of classical antiquity and the philosophies underpinning the various Greek and Roman societies, men like Thomas Jefferson and James Madison relied firmly on what they had learned as they were envisioning the American Republic (and, to be certain, Jefferson found great inspiration from the Greeks and the Romans in his architectural pursuits as well).

Nowhere is this more evident than in Federalist #38. Written by Madison, this essay continues his efforts to counter the rhetoric of those opposed to the ratification of the Constitution—focusing squarely on the flaws in those opponents’ reasoning, and drawing on the lessons of history in order to sway support in favor of ratification.

After briefly discussing the Minoans, the Spartans, and the Romans, Madison focuses on Athens—the cradle of early democracies (the word “democracy” is in and of itself Greek, meaning “ruled by the people”). After discussing some of what led to the formation of the Athenian democratic government, he asks by the people of Athens,

“should consider one illustrious citizen as a more eligible depositary of the fortunes of themselves and their posterity, than a select body of citizens, from whose common deliberations more wisdom, as well as more safety, might have been expected?”

In other words, there was concern as to whether one person—whether a “divine right” monarch or someone selected through a democratic process—would serve the nation (though in the case of the Greeks we’re generally talking about “city states” better than some group of citizens, acting together to make decisions.

In fact, Athens made participation in their democracy mandatory, and each year a group of citizens would be compelled to serve in the government.

Madison then goes on to talk about the challenges that the founders of these governments faced, showing that there is indeed a lesson in the debates that existed in Greece and Rome for those debating the ratification of the Constitution:

“History informs us, likewise, of the difficulties with which these celebrated reformers had to contend, as well as the expedients which they were obliged to employ in order to carry their reforms into effect.”

In other words—these men faced challenges, too, but those challenges did not prevent them from moving forward with improvements. But most important is the lesson that correcting the mistakes of governance in the past is an essential element of a successful and enduring nation, while at the same time recognizing that opposition for opposition’s sake can be needlessly complicating:

“If these lessons teach us, on one hand, to admire the improvement made by America on the ancient mode of preparing and establishing regular plans of government, they serve not less, on the other, to admonish us of the hazards and difficulties incident to such experiments, and of the great imprudence of unnecessarily multiplying them.”

This is the real focus of Madison’s essay—his accusation to the critics of the Constitution that their arguments are not in any way constructive or substantive, but worse, that they are (in many cases) contradictory and harmful in that they are needlessly delaying the lawful formation of a national government.

The Constitution was meant as a necessary improvement over the Articles of Confederation, a document that, like many implemented first drafts, was found to be wanting and ultimately unworkable. It was a document full of contradictions—a central government given responsibilities but little authority to exercise those responsibilities. In fact, it could be said that this is by design, that these flaws were embedded in the Articles of Confederation to make that document (and any government trying to operate under it) unworkable (in modern legal parlance, this is referred to as a “poison pill”).

But Madison knew time was of the essence—and that pointing out the contradictions in the arguments of the Constitution’s opponents was essential to the speedy adoption of that document, framing it as a mortal health issue:

“A patient who finds his disorder daily growing worse, and that an efficacious remedy can no longer be delayed without extreme danger, after coolly revolving his situation, and the characters of different physicians, selects and calls in such of them as he judges most capable of administering relief, and best entitled to his confidence. The physicians attend; the case of the patient is carefully examined; a consultation is held; they are unanimously agreed that the symptoms are critical, but that the case, with proper and timely relief, is so far from being desperate, that it may be made to issue in an improvement of his constitution…

“Such a patient and in such a situation is America at this moment. She has been sensible of her malady. She has obtained a regular and unanimous advice from men of her own deliberate choice. And she is warned by others against following this advice under pain of the most fatal consequences. Do the monitors deny the reality of her danger? No. Do they deny the necessity of some speedy and powerful remedy? No.”

Sometimes, we forget the precarious nature of the fledgling American republic. Yes, we had just won the war for our independence, but the nation’s future was hardly guaranteed. In fact, it was even more precarious because of the failure of the Articles of Confederation in producing the balancing of interests between the states, the central government, and the people themselves.

Ultimately, Madison prevailed upon the readers of his essays to consider that as flawed as the Constitution might be, it was better than either of the two alternatives (as he saw them): the Articles of Confederation or no organizing document whatsoever. Whichever the particular complaints of the Constitution’s opponents, Madison needed them to see that point. With the past being prologue, Madison knew what would happen to the American experiment otherwise.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!