Principle of Peace, Commerce and Honest Friendship With All Nations, Entangling Alliances With None

Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

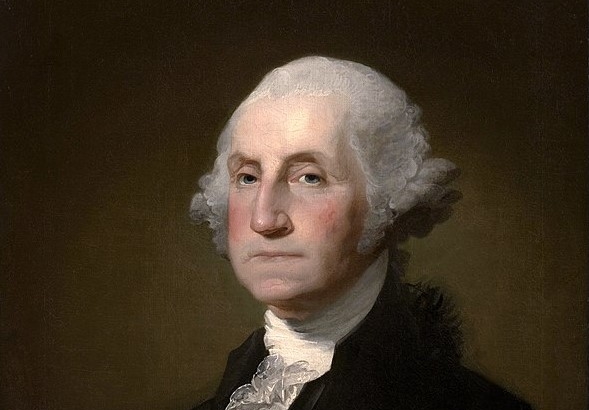

“The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible. So far as we have already formed engagements, let them be fulfilled with perfect good faith…Our detached and distant situation invites and enables us to pursue a different course. If we remain one people under an efficient government. the period is not far off when we may defy material injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel. Why forego the advantages of so peculiar a situation? Why quit our own to stand upon foreign ground? Why, by interweaving our destiny with that of any part of Europe, entangle our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor or caprice? It is our true policy to steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world; so far, I mean, as we are now at liberty to do it; for let me not be understood as capable of patronizing infidelity to existing engagements…Taking care always to keep ourselves by suitable establishments on a respectable defensive posture, we may safely trust to temporary alliances for extraordinary emergencies.” – George Washington, Farewell Address, first published September 19, 1796 in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser and given the date September 17, 1796.

When George Washington assumed the office of the presidency in 1789, the new republic faced a world fraught with imperial rivalries of the European great powers. This struggle played itself out in North America where the British ruled Canada and had troops stationed in forts along the northwestern frontier of the United States. The Spanish held Mexico, the West, and the Floridas. Meanwhile, the new nation soon went to war with several hostile Native American tribes on the frontier. Several powers, including the French, contended for the valuable sugar islands of the West Indies, or Caribbean. The British Empire excluded its former colonies from lucrative imperial trade.

Washington and his Cabinet along with members of Congress had to formulate the principles and policies of American foreign policy according to the dictates of constitutionalism, American ideals, and prudence. The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 and its expansionary wars compounded the difficulties of American diplomacy in the early 1790s.

President Washington had to navigate these shoals keeping in mind that the new nation was weak compared to the great empires. The United States had only a small army and not much of a navy. The economy was similarly weak as the country was locked out of former markets in the British West Indies and had to get its public credit in order by paying off the Revolutionary War debt. National security was a priority for the Washington administration but securing it would not be easy.

When the French revolutionaries sought to spread the fires of revolution to liberate the people of Europe from monarchy and aristocracy, Washington had to decide an appropriate response for the new nation. Washington and his Cabinet debated the issue and prudentially decided that it was ill-prepared for war and would not join the French despite their 1778 treaty from the American Revolution. The United States would remain neutral with a presidential Proclamation of Neutrality.

This led to an internal debate within the administration that was played out in essays published in partisan newspapers. Among them were Alexander Hamilton writing as Pacificus, who urged presidential prerogative over asserting neutrality, and James Madison writing as Helvidius, who thought the Congress had power over war and peace. The debate fueled the emerging contentious party system and split the administration into factions.

The Washington administration pursued a policy of trade and non-interference, but the British and French were at war and began seizing American vessels because they traded with each of the belligerents. Soon, Washington dispatched John Jay to Britain to resolve the seizure of ships, impressment of American sailors into the Royal Navy, and outstanding issues from the Revolutionary War including western British forts.

The resulting Jay Treaty benefited the United States, including some trade concessions in the West Indies, but it did not resolve many of the key issues including impressment. Moreover, it further inflamed partisan tensions among Americans and in Congress. Even worse, as it soothed relations with Great Britain, the French saw it as an Anglo-American alliance aimed against France. The French became more belligerent and ramped up their seizure of American vessels leading to an informal war that continued into the John Adams administration.

In 1795, the administration signed the Pinckney Treaty with Spain which extended the western boundary of the United States to the Mississippi River. Americans also won long-contested rights to free navigation of the Mississippi River to conduct trade.

By the end of his second term, President Washington could proudly survey the diplomatic accomplishments of his administration. From a position of relative weakness, he had averted war, successfully negotiated important treaties, established a strong presidency respecting foreign policy, and placed the country in a stronger position in a dangerous world. As he prepared to retire and worked on his Farewell Address to his fellow countrymen, he used his decades of experience as general and president to lay down certain principles of American foreign policy.

In his Farewell Address, Washington asserted that it should be the policy of the United States to “steer clear of permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” He explained that it should be the principle of the United States to establish “peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations, entangling alliances with none. The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.”

Washington promoted an enlightened and principled national self-interest in foreign relations. The United States would pursue its self-interest trading with other nations and forming temporary alliances in its interest. As the French example proved, a nation might be a friend at one point but could become an enemy at another. So, the United States would not form a permanent alliance that would bind it in an untenable situation. Instead, as with all nations, it would pursue its own interest.

However, Washington strikes an important chord of principled self-interest according to the founding ideals of an exceptional nation. In the Address, he speaks of “amity,” “justice,” “liberality,” “good faith,” and “harmony” as the principles guiding American relations with the other countries of the world. He proposed the idea that America should demonstrate a good example for the world. He wrote, “It will be worthy of a free, enlightened, and, at no distant period, a great nation, to give to mankind the magnanimous and too novel example of a people always guided by an exalted justice and benevolence.”

American foreign policy has changed over the last two centuries. Successive administrations through the nineteenth century generally followed Washington’s vision; however, during the twentieth century, President Woodrow Wilson helped commit the United States to “making the world safe for democracy” and exporting it abroad. Wilsonian internationalism meant that the United States would not merely be a “City Upon a Hill” for other countries to emulate its ideals but would take an active role in bringing about more democratic regimes. This expansive and controversial foreign policy was at odds with Washington’s vision in the Farewell Address. George Washington’s words and example reminds us to exercise justice and good faith toward other nations but also defending American national security with enlightened self-interest.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!