Barriers Against Encroachments on Individual Natural Rights of Life, Liberty and Property: America’s Founders and a Well-constructed Constitution

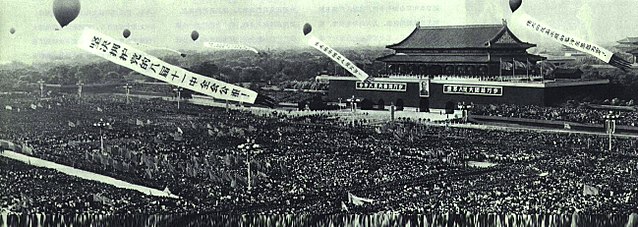

Mao Zedong’s bloody “The Cultural Revolution” led to the violation of life, liberty and property for millions of people. Though Mao claimed this was a revolution to promote communism and purge China of capitalism, it was also a manifestation of the kind of tyrannical faction that James Madison and other Framers of the United States Constitution warned about.

Mao’s Revolution was grounded upon a rejection of the tradition that human beings have natural rights as individuals, substituting instead the idea that people are, can, and should be simply “programmed” to behave as government desires with the right kinds of physical and psychological measures. According to Maoist ideology, human beings have absolutely no natural rights – including the right to life and property – that must be respected.

The American Founders, including Federalists and Anti-federalists, foresaw the kind of unspeakable horrors that could be unleashed when the idea of individual natural rights is rejected and abused by government or powerful leaders. As Anti-federalist Brutus wrote, Americans deeply believed that “all men are by nature free. No one man, therefore, or any class of men, have a right, by the law of nature, or of God, to assume or exercise authority over their fellows…This principle, which seems so evidently founded in the reason and nature of things, is confirmed by universal experience.”

Brutus understood very well that human beings, when entrusted with power, are prone to abuse that authority for their own purposes. “Those who have governed, have been found in all ages ever active to enlarge their powers and abridge the public liberty,” Brutus wrote. “This has induced the people in all countries, where any sense of freedom remained, to fix barriers against the encroachments of their rulers.” Brutus points out that the state constitutions at the time provided many of these “barriers” in the form of “due process of law” as protection for the individual natural rights of citizens.

For the security of life, in criminal prosecutions, the bills of rights of most of the states have declared, that no man shall be held to answer for a crime until he is made fully acquainted with the charge brought against him; he shall not be compelled to accuse, or furnish evidence against himself—the witnesses against him shall be brought face to face, and he shall be fully heard by himself or counsel.

Constitutional barriers also protected the individual natural right to private property. As Brutus writes, “For the purpose of securing the property of the citizens, it is declared by all the states, “that in all controversies at law, respecting property, the ancient mode of trial by jury is one of the best securities of the rights of the people, and ought to remain sacred and inviolable.”[1]

Federalist James Madison also believed that for government to be just it must protect the individual right to private property. In The Federalist No. 10, Madison wrote about how the different kinds and degrees of property people acquire, hold, and use are a reflection of human nature. “The diversity in the faculties of men, from which the rights of property originate,” Madison wrote, makes it difficult, if not impossible, for government to impose by force a universal uniformity of opinion (as Mao had attempted to do in the Cultural Revolution). “The protection of these faculties is the first object of government. From the protection of different and unequal faculties of acquiring property, the possession of different degrees and kinds of property immediately results.”[2]

For James Madison, “property” meant more than just ownership of material things and goods, such as “a man’s land, or merchandize, or money.” In a larger sense, Madison wrote:

[A] man has a property in his opinions and the free communication of them. He has a property of peculiar value in his religious opinions, and in the profession and practice dictated by them. He has a property very dear to him in the safety and liberty of his person. He has an equal property in the free use of his faculties and free choice of the objects on which to employ them. In a word, as a man is said to have a right to his property, he may be equally said to have a property in his rights.[3]

Just as the physical property one owns is acquired through physical labor, the opinions we hold – especially our religious opinions – are the products of the labor of our minds. And Madison, like Thomas Jefferson, believed that the human mind is made free by nature – or, as Jefferson put it, “Almighty God hath created the mind free.”[4] To violate the rights of property in either sense – as Maoist ideologues attempted to do during the Cultural Revolution – is to deny the natural freedom of the human mind.

Anti-federalists and Federalists understood that one of the best means for preventing abuses of natural rights is to find a way to prevent all political power from being held in the same hands. As Brutus wrote, “When great and extraordinary powers are vested in any man, or body of men, which in their exercise, may operate to the oppression of the people, it is of high importance that powerful checks should be formed to prevent the abuse of it.”[5] Federalist James Madison agreed: “The accumulation of all powers, legislative, executive, and judiciary, in the same hands, whether of one, a few, or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”[6] As we have discussed in earlier essays, Madison and the Federalists believed that the best way to keep power diffused was to separate powers through a combination of modes of election, qualifications for office, and different terms in office for the various branches of government. All of these constitutional barriers – from mandatory due process of law to the manner in which powers are separated – help to provide checks against the kinds of actions taken by Mao and his Revolutionaries with regard to violations of the individual natural rights of life, liberty, property, and religious liberty, and make the kinds of bloody “purges” of the Cultural Revolution less likely under a well-constructed Constitution.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

[1] Brutus II.

[2] The Federalist No. 10.

[3] James Madison, “Property,” 29 March 1792.

[4] Thomas Jefferson, “A Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom” in Virginia, written 1779, enacted 1786.

[5] Brutus XVI.

[6] The Federalist No. 47.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1967-03_1966%E5%B9%B412%E6%9C%8826%E6%97%A5%E6%B1%9F%E9%9D%92%E5%91%A8%E6%81%A9%E6%9D%A5%E5%BA%B7%E7%94%9F%E6%8E%A5%E8%A7%81%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1967-03_1966%E5%B9%B412%E6%9C%8826%E6%97%A5%E6%B1%9F%E9%9D%92%E5%91%A8%E6%81%A9%E6%9D%A5%E5%BA%B7%E7%94%9F%E6%8E%A5%E8%A7%81%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

So this might be what those working on controlling our government are trying to take away from us?