King vs. Parliament in 17th Century England: From Absolutism to Constitutional Monarchy, Influence on American Governing

There have been few times as crucial to the development of English constitutional practice as the 17th century. The period began with absolute monarchs ruling by the grace of God and ended with a new model of a constitutional monarchy under law created by Parliament. That story was well known to the Americans of the founding period.

The destructive civil wars between the houses of York and Lancaster, known as the War of the Roses, ended with the seizure of the throne by Henry VII of the Welsh house of Tudor in 1485. The shifting fortunes in those wars had shattered many prominent noble families. Over the ensuing century, the Tudor monarchs, most prominently Henry VIII and Elizabeth I, consolidated royal power. Potential rivals, such as the nobility and the religious leaders, were neutralized by property seizures, executions, and dependence on the monarch’s patronage and purse for status and livelihood. Economic and social change in the direction of a modern commercial nation-state and away from a feudal society where wealth and status were based on rights in land had already begun before those wars. This change was due to financial necessities and a nascent sense of nationalism arising from the Hundred Years’ War between the English Plantagenet kings and the French house of Valois. Under the Tudors, England’s transition to a distinctly modern polity with a clear national identity was completed.

When Elizabeth died childless, the Tudor line came to an end, and the throne went to James VI Stuart of Scotland, who became James I of England, styling himself for the first time, “King of Great Britain.” On the whole, James was a capable and serious monarch but had strong views about his role as king. His pugnaciousness brought him into conflict with an increasingly assertive Parliament and its allies among the magistrates, especially his Attorney General and Chief Justice, Sir Edward Coke. The need for revenues to pay off massive debts incurred by Elizabeth’s war with Spain was the catalyst for the friction. James was well educated in classic humanities and had a moderate literary talent. He wrote poetry and various treatises. He also oversaw the production of the new English translation of the Bible. As a side note, I have found it amusing that, 400 years ago, James warned about the dangers of tobacco use.

It was James’s political writing, however, which irked Parliament. He was a skillful defender of royal prerogative and seemed to derive satisfaction from lecturing his opponents in that body about the inadequacies in their arguments. James was able to navigate relations with Parliament successfully on the whole, mostly by just refusing to call them into session. But his defense and exercise of his prerogatives, his claim to rule as monarch by the grace of God, and his pedantic and irritating manner, coupled with the restlessness of Parliament after more than a century of strong monarchs, set the stage for confrontation once James departed this mortal coil.

Parliamentary authority had accreted over the centuries through a process best described as punctuated equilibrium, to borrow from evolutionary biology. Anglo-Saxon versions of assemblies of noble advisors to the king existed before the Norman Conquest, in accordance with the customs of other Germanic peoples. William the Conqueror similarly established a council of great secular and ecclesiastical nobles of the realm, whom kings might summon if they needed advice or political support before issuing laws or assessing taxes. This rudimentary consultative role was expanded when the council of English barons gathered at Runnymede in 1215 and forced King John to agree to a Magna Carta. A significant provision of that charter required the king to obtain the consent of his royal council for any new taxes except those connected to his existing feudal prerogatives. This was a major step in developing a legislative power which future parliaments guarded jealously.

In 1295, Edward I summoned his Great Council in what the 19th-century English historian Frederic William Maitland called the Model Parliament because of the precedent it set. This Great Council included not just 49 high nobles, but also 292 representatives from the community at large, later referred to as the “Commons,” composed of knights of the shire and burgesses from the towns. Edward formalized what had been the practice off and on for several decades at that point. Another constitutional innovation was Edward’s formal call for his subjects to submit petitions to this body to redress grievances they might have. This remains a vital constitutional right of the people in England and the United States.

The division of the Great Council into two chambers occurred in 1351, with the high nobility meeting in what later came to be known as the House of Lords and the knights and burgesses meeting in the House of Commons. Within the next few decades, parliaments increasingly insisted that they controlled not just taxation, but also the other side of the power over the purse, expenditures. They faced some hurdles, however. Parliaments had no right to meet, and kings might fail to summon such a gathering for years. Also, these bodies were in no sense democratic. The Lords were a numerically small elite. Due to property restrictions, the Commons, too, represented a thin layer of land-owning gentry and wealthy merchants. The degree to which bold claims of parliamentary power succeeded depended primarily on the political skill of the monarch. Strong monarchs, such as most of the Tudors, could either decline to call parliament into session or push needed authorization through dint of their standing among powerful and respected members of those bodies. A politically adept king could secure those relationships through a judicious use of his patronage to appoint favorites to offices.

During the rule of James I, parliamentary opponents of the king increasingly expressed their displeasure through petitions to redress grievances. English parliaments also manipulated the process as a tool of political power against the king. While those petitions might in fact come directly from disgruntled constituents, they were often contrived by members of Parliament using constituents as straw men to initiate debate in a way which suggested popular opposition to the monarch on a matter. These were political theater, albeit sometimes politically effective. Even if such a petition were granted by Parliament when in session, relief would have to come through the king or his officials, an unlikely result.

After the death of James I, relations between king and Parliament deteriorated further under his son. More affable than his father, Charles I was also less politically astute. As adamant as his father had been about protection of royal prerogative, Charles made too many political missteps, such as arresting members of Parliament who opposed various policies. Much of his political trouble arose from England’s precarious financial situation, partly due to misbegotten and unpopular military campaigns precipitated by Charles’s foreign minister, the Duke of Buckingham. When Parliament proved uncooperative, he attempted to finance these ventures and various household expenses through technically legal, but constitutionally controversial, workarounds.

One constitutional theory held that taxes, especially direct taxes on wealth or persons, were not part of the king’s prerogative. Rather, such taxes were “gifts” from the people. As with other gifts, the king might ask but could not compel. The people could refuse. It was impractical to ask each person. Instead, the Commons collectively could vote to grant such a gift to the king. The king had the prerogative, however, to enforce feudal obligations, collect fees, or sell property to raise funds. When Parliament in 1626 refused to vote taxes to pay for the military expeditions, Charles instead imposed “forced loans” on various individuals. Although such loans were deemed legal by the courts, this constitutional legerdemain was exceedingly unpopular and failed to produce significant income. Worse for the king, Parliament adopted the Petition of Right in 1628, which, in part, reaffirmed Parliament’s sole power of taxation. Charles at first agreed, but soon reneged. He dismissed Parliament and reasserted his power at least to collect customs duties. The Petition would prove to be significant eventually for another reason, because it also asserted certain rights which the king could not invade.

Charles then ruled without Parliament. To pay for his expenses, he resorted to various arcane levies, fees, fines, rent assessments, and sales of monopoly licenses. Still, he ran out of funds by 1640. Needing money for a military campaign against the Scots, he called Parliament into session. The first session proved unproductive, but he summoned another Parliament, which met in various forms for most of the next twenty years and became known collectively as the Long Parliament. Friction between Charles and Parliament led to civil war, a military coup by General Oliver Cromwell and other officers of the New Model Army, the trial of Charles by a “Rump Parliament” purged of his supporters by the Puritan military, and the regicide in 1649.

Following the execution of Charles, the Rump Parliament abolished the monarchy and proclaimed England to be a “Commonwealth.” Deep political divisions remained. If anything, executing who historians consider one of the most popular English kings undermined the legitimacy of the Commonwealth with the people. Cromwell finally dismissed the Rump Parliament forcibly in 1653, after scorning them with the splendidly pungent “In the name of God, go!” speech the likes of which would not be heard today.

The Protectorate established later that year did not smooth relations between Parliament and Cromwell. In essence, this was a military dictatorship, and even the absence of royalists in the Commons and the interim abolition of the House of Lords did not prevent opposition to him. The two Protectorate Parliaments also were dissolved by Cromwell when they proved insufficiently cooperative, especially in matters of taxation, and too radically republican for Cromwell’s taste, having dared to challenge the Lord Protector’s control over the military.

Although the Protectorate’s military government was an aberration in English history, it produced some notable constitutional developments. The Instrument of Government of 1653 and the Humble Petition and Advice of 1657 collectively are the closest England has come to a formal written constitution. They created a structure of checks and balances which captured the trend of the English system from an absolutist royal rule to a limited “constitutional” monarchy. Although these two documents eventually were jettisoned by the “Cavalier Parliament” after the Restoration, they became a model for resolution of a subsequent constitutional crisis.

The Instrument provided the basic structure of government for the Protectorate. It was drafted by the radical republican Puritan General John Lambert and adopted by the Army Council of Officers in 1653. It was based on proposals which had been offered in 1647 to settle the constitutional crisis with Charles I, but which the king had rejected. The Instrument set up a division of power among the Lord Protector, a Council of State, and a Parliament that was to meet at least every three years. The last had the sole power to tax and to pass laws. The Protector had a qualified veto over the Parliament’s bills. However, he had an absolute veto over laws which he deemed contrary to the instrument itself. Moreover, Parliament could not amend the Instrument. Although these provisions put Cromwell in the position of final authority over this “constitution,” the proposition that Parliament was limited by a higher law contradicted principles of Parliamentary supremacy. It anticipated the later American conception of the relationship between a constitution and ordinary legislative bodies. The Humble Petition and Advice was adopted by Parliament in 1657. It proposed some amendments to the Instrument, among them making Cromwell “king” and creating the “Other House,” a second chamber of Parliament, composed of life-term peers. Cromwell rejected the first and accepted the second.

After Cromwell’s death in 1658, and the resignation of his son Richard as Lord Protector the following year, the Protectorate ended. This created a political vacuum and a danger of anarchy. In the end, one of Cromwell’s trusted leaders, General George Monck, led elements of the New Model Army to London to oversee the election of a new “Convention Parliament.” Though Monck had been personally loyal to both Cromwells, he was also a moderate Royalist. The new Parliament technically was not committed either to the Commonwealth or the monarchy. However, it was controlled by a Royalist majority, and popular sentiment was greatly in favor of abolishing the military government and restoring the monarchy. Monck sent a secret message to Charles II for the prince to issue a declaration of lenity and religious toleration. After Charles complied, Parliament invited him to return as king.

Although the new king also fervently believed in his divine right to rule and proceeded to undo the Protectorate’s laws and decrees through his friends in Parliament—which again included the restored House of Lords—he was savvy enough not to stir up the hornet’s nest of Stuart absolutism too vigorously. A period of relative constitutional calm ensued, although Whig exponents of radical theories of popular sovereignty and revolution could still find their works used against them as evidence of treason and plotting.

Upon Charles’s death in 1685, the crown went to his brother, James II, an enthusiastic convert to Catholicism. When he and his wife, Mary of Modena, had a son in 1688, it presented the clear possibility of a Catholic dynasty, a scenario which repelled the Anglican hierarchy. Even more objectionable were James’s exertions at blunting the Test Acts and other laws which discriminated against Catholics and Protestant dissenters from the established Anglican Church. The main tool was his dispensing power, a prerogative power to excuse conformance to a law. But, at the likely instigation of the Quaker, William Penn, he also issued his Declaration for Liberty of Conscience in 1687, a major step towards freedom of worship. The Declaration suspended penal laws which required conformity to the Anglican Church.

James’s Anglican political supporters began to distance themselves from him, and seven Protestant nobles invited the Stadholder of the United Netherlands, William of Orange, to bring an army to England. The Glorious Revolution had begun. James initially planned to fight the Dutch invasion, but lost his nerve and tried to flee to France. He was captured and placed under the guard of the Dutch. William saw no upside to having to oversee the fate of James, who was his uncle and father-in-law. To rid himself of this annoyance, he let James escape to France.

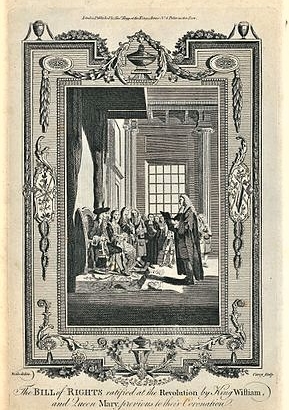

With James gone, William refused the English crown unless it was offered to him by Parliament. At the behest of a hastily gathered assembly of peers and selected commoners, William summoned a “Convention Parliament.” The throne was declared vacant due to James’s abdication. The Convention Parliament drafted and adopted the Declaration of Right. The following day, February 13, 1689, they offered the crown to William and Mary together as King and Queen, with William alone to have the regal power during his life. After accepting the crown, William dismissed the Convention Parliament and summoned it to reconvene as a traditional parliament.

The Convention Parliament was another milestone in the development of Anglo-American constitutional theory and built on the earlier Protectorate’s Instrument of Government. The process instantiated the radical idea that forming a government is different than passing legislation, in that the former is, in the later phrasing of George Washington, “an explicit and authentic act of the people.” The opponents of the Stuarts had long claimed that all power was derived originally from the people. However, parliaments had challenged the king’s supremacy with the claim that they represented the estates of nobles and commons, and that the people had vested all constitutive power in them. But, if the people were truly the ultimate source of governmental legitimacy, how could they permanently surrender that to another body? This debate was carried on among the Whig republican thinkers of the era, such as the radical Algernon Sidney and the moderate John Locke. It raised knotty and uncomfortable issues about revolution. Those very problems would occupy Americans for several decades from the 1760s on in the drive toward independence and the subsequent process of creating a government.

There was no concrete condition that William and Mary accept the Declaration, but the crown was offered on the assumption that the monarch would rule according to law. That law included the provisions of the Declaration, once the reconvened parliament passed it as the Bill of Rights in December, 1689. Until then, the Declaration had no force of law, not having been adopted by Parliament as a legislative body and not having received the Royal Assent. This has been the process of the unwritten English constitution. As with the various versions of the Magna Carta and other famous charters and proclamations, an act of Parliament is required to make even such fundamental arrangements of governance legally binding. The English Bill of Rights is, mostly, still a part of that unwritten constitution, although some provisions have been changed by subsequent enactments.

The English Bill of Rights built on the Petition of Right to Charles I in 1628 and the Habeas Corpus Act of 1679 in expressly guaranteeing certain rights. Among them were protections to petition for redress of grievances, to have arms for self-defense for Protestants, against cruel and unusual punishments or excessive bail or fines, and for trial by jury. Moreover, it protected members of Parliament from prosecution for any speech or debate made in that body. Many of these same protections appeared in American colonial charters, early American state constitutions, the petitions of state conventions ratifying the Constitution, and the American Bill of Rights. At first glance, the failure to protect religious liberty seems to be a glaring omission. However, anti-Catholic feelings ran high, and, contrary to James II, the Anglican majority was not in the mood for religious tolerance. As to Protestant Nonconformists, their religious liberty was recognized in the Toleration Act of 1689.

The Bill of Rights also made it clear that the monarch holds the crown under the laws of the realm, thereby rejecting the Tudor and Stuart claims of ruling by divine grace. This postulate was a crucial step in the evolution towards a “constitutional” monarchy. Following the approach of the Protectorate’s Instrument of Government, the Bill of Rights provided that laws must be passed by Parliament, although the monarch had an unqualified power to withhold consent. One must note, however, that this veto power has not been exercised since 1708 by Queen Anne. An attempt to do so by a British monarch today might trigger a constitutional crisis.

As a reaction against the perceived Catholic sympathies of the Stuarts and, in James II’s case, his actual Catholicism, the Bill of Rights very carefully designated the line of succession if, as happened, William and Mary died childless. That line of succession was limited to what were traditional Protestant families. To make the point clearer, the Bill of Rights defiantly debarred anyone who “is … reconciled to, or shall hold communion with, the see or church of Rome, or shall profess the popish religion, or shall marry a papist …” from the throne. The last prohibition likely was due to the habit of the Stuart kings to marry devout Catholic princesses, and an understandable concern over the influence that such a spouse might have in spiritual matters. On that point, too, the English experience affected later American developments, with the protection of religious freedom in the Bill of Rights and the prohibition of religious test oaths in the Constitution.

In addition to the importance of these historical antecedents to American constitutional development, the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution demonstrate an uncomfortable truth. When the ordinary means of resolving fundamental matters of governance prove unavailing, those matters will be resolved by violence. Constitutional means work during times of relative normalcy, but on occasion the contentions are infused with contradictions too profound for compromise. It is an axiom of politics that politicians will seek first to protect their privileges and second to expand them. The increased demands by parliamentarians for political power inevitably clashed with the monarchs’ hereditary claims. Both sides appealed to traditional English constitutional custom for legitimacy. With their assumptions about the source of political authority utterly at odds, compromise became increasingly complex and fleeting. It was treating a gangrenous infection with a band-aid. Radical surgery became the way out. The American Revolution in the following century, and even the American Civil War of the century thereafter, showed evidence of a similar progression, with the two sides operating from fundamentally contradictory views of the nature of representative government and proper division of power between the general government and its constituent parts.

The Glorious Revolution resolved the contest over these conflicting views of legitimate authority and the proper constitutional order between king and Parliament. The earlier Commonwealth with its Protectorate was an abortive step in the same direction. It failed due to the political shortcomings of the military leaders in control. Although further adjustments would be made to the relationship between monarch and parliaments, the basic constitutional order of a limited monarchy reigning within a political structure of Parliamentary supremacy was set. The new constitutional arrangement became a model for political writers of the 18th century, such as the Baron de Montesquieu. American propagandists of the revolutionary period readily found fault with the British system. Once they turned to forming governments, however, Americans more dispassionately studied and learned from the mother country’s rocky path to a more balanced and “republican” government in the 17th century. Both sides in the debate over the Constitution regularly used the British system as a source of support for their position or to attack their opponents.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!