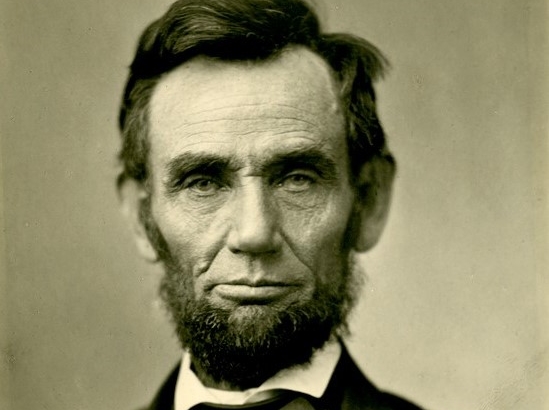

The tall, awkwardly boned, young Illinois legislator rose to speak. His thick hair, impervious to the comb, splayed over his head. The crowd at the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield leaned forward. They did not know it, but they were about to hear a prophet.

The title of Lincoln’s address was “The Perpetuation of Our Political Institutions.” It could have been subtitled, “Will this nation survive?” From the moment his high-pitched voice began to address the audience, Lincoln’s passionate embrace of the Constitution set his life out on an arc that would carry him a quarter century later to Gettysburg when he asked whether a nation conceived in liberty “can long endure.” He was asking it even now.

Yet 1838 was not such a bad year. True, the nation was struggling through the effects of the Panic of 1837, and it would be a few years before a recovery could take hold. But the wrenching crises of slavery and nullification that nearly severed the Union were in the past—at least many hoped so. The Missouri Compromise of 1820, it was thought, had settled the geographical boundary that separated the slave from the free. And in 1831, Andrew Jackson had squelched South Carolina’s attempt at nullification. The trio of Daniel Webster, John C. Calhoun, and most especially Henry Clay—Lincoln’s idol—had fashioned peace through compromise. The Annexation of Texas, the Mexican War, the Compromise of 1850, the Kansas-Nebraska Act, Dred Scott, and John Brown were still in the unknowable future.

But Lincoln was not mollified. He saw the nation falling apart right then and there. Vigilantism and brutal violence were everywhere rampant. There was a contagion of lynching. Lincoln reviewed what all knew had been happening. First, five gamblers in Vicksburg were strung up. “Next, negroes suspected of conspiring to raise an insurrection were caught up and hanged in all parts of the State; then, white men supposed to be leagued with the negroes; and finally, strangers from neighboring States, going thither on business, were in many instances subjected to the same fate. Thus went on this process of hanging, from gamblers to negroes, from negroes to white citizens, and from these to strangers, till dead men were seen literally dangling from the boughs of trees upon every roadside, and in numbers almost sufficient to rival the native Spanish moss of the country as a drapery of the forest.” A Negro named McIntosh, accused of murdering a white man, was tied to a tree and burnt to death. Abolitionist editors were slain and their printing presses thrown in the river. This, Lincoln said, was mob law.

The founders, who gave us a blessed government, were now gone– “our now lamented and departed race of ancestors,” he told his listeners. The last had only recently passed. (It was James Madison, the “father of the Constitution,” who died in 1836). What can we do without them? Lincoln asked. What then can save us from dissolution, from turning ourselves into a miserable race, nothing more than a vengeful mob?

Lincoln paused, and then declared, “The answer is simple. Let every American, every lover of liberty, every well-wisher to his posterity swear by the blood of the Revolution never to violate in the least particular the laws of the country, and never to tolerate their violation by others. As the patriots of seventy-six did to the support of the Declaration of Independence, so to the support of the Constitution and laws let every American pledge his life, his property, and his sacred honor — let every man remember that to violate the law is to trample on the blood of his father, and to tear the charter of his own and his children’s liberty.”

On that day, January 27, 1838, Lincoln set his course. It was Lincoln’s charter of the rest of his public life. The Constitution. Only reverence for it and for the law can keep us from becoming divided tribes ruled by our passions, he told the crowd in the Young Men’s Lyceum, and other crowds in the coming decades. Reverence for the Constitution saved the Union in the bitter election of 1800. It energized Henry Clay and his political enemy, Andrew Jackson, to keep the states tied together. It steeled Lincoln in his perseverance to see the Civil War through to victory.

It can save us yet.

David F. Forte is Professor of Law at Cleveland State University, Cleveland-Marshall College of Law, where he was the inaugural holder of the Charles R. Emrick, Jr. – Calfee Halter & Griswold Endowed Chair. He has been a Fulbright Distinguished Chair at the University of Warsaw and the University of Trento. In 2016 and 2017, Professor Forte was Garwood Visiting Professor at Princeton University in the Department of Politics. He holds degrees from Harvard College, Manchester University, England, the University of Toronto and Columbia University.

During the Reagan administration, Professor Forte served as chief counsel to the United States delegation to the United Nations and alternate delegate to the Security Council. He has authored a number of briefs before the United States Supreme Court and has frequently testified before the United States Congress and consulted with the Department of State on human rights and international affairs issues. His advice was specifically sought on the approval of the Genocide Convention, on world-wide religious persecution, and Islamic extremism. He has appeared and spoken frequently on radio and television, both nationally and internationally. In 2002, the Department of State sponsored a speaking tour for Professor Forte in Amman, Jordan, and he was also a featured speaker to the Meeting of Peoples in Rimini, Italy, a meeting that gathers over 500,000 people from all over Europe. He has also been called to testify before numerous state legislatures across the country. He has assisted in drafting a number of pieces of legislation both for Congress and for the Ohio General Assembly dealing with abortion, international trade, and federalism. He has sat as acting judge on the municipal court of Lakewood Ohio and was chairman of Professional Ethics Committee of the Cleveland Bar Association. He has received a number of awards for his public service, including the Cleveland Bar Association’s President’s Award, the Cleveland State University Award for Distinguished Service, the Cleveland State University Distinguished Teaching Award, and the Cleveland-Marshall College of Law Alumni Award for Faculty Excellence. He served as Consultor to the Pontifical Council for the Family under Pope Saint John Paul II and Pope Benedict XVI. In 2004, Dr. Forte was a Visiting Professor at the University of Trento. Professor Forte was He has given over 300 invited addresses and papers at more than 100 academic institutions.

Professor Forte was a Bradley Scholar at the Heritage Foundation, Visiting Scholar at the Liberty Fund, and Senior Visiting Scholar at the Center for the Study of Religion and the Constitution in at the Witherspoon Institute in Princeton, New Jersey. He has been President of the Ohio Association of Scholars, was on the Board of Directors of the Philadelphia Society, and is also adjunct Scholar at the Ashbrook Institute. He is Vice-Chair of the Ohio State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights.

He writes and speaks nationally on topics such as constitutional law, religious liberty, Islamic law, the rights of families, and international affairs. He served as book review editor for the American Journal of Jurisprudence and has edited a volume entitled, Natural Law and Contemporary Public Policy, published by Georgetown University Press. His book, Islamic Law Studies: Classical and Contemporary Applications, has been published by Austin & Winfield. He is Senior Editor of The Heritage Guide to the Constitution (2006), 2d. edition (2014) published by Regnery & Co, a clause by clause analysis of the Constitution of the United States.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.