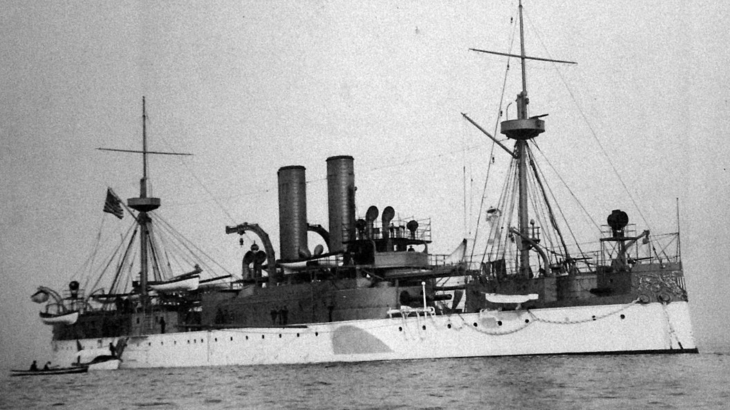

February 15, 1898: Battleship Maine Blows Up, Leads to the Spanish-American War and America Enters the World Stage

On February 15, 1898, an American warship, U.S.S. Maine, blew up in the harbor of Havana, Cuba. A naval board of inquiry reported the following month that the explosion had been caused by a submerged mine. That conclusion was confirmed in 1911, after a more exhaustive investigation and careful examination of the wreck. What was unclear, and remains so, is who set the mine. During the decade, tensions with Spain had been rising over that country’s handling of a Cuban insurgency against Spanish rule. The newspaper chains of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer had long competed for circulation by sensationalist reporting. The deteriorating political conditions in Cuba and the harshness of Spanish attempts to suppress the rebels provided fodder for the newspapers’ “yellow” journalism. Congress had pressured the American government to do something to resolve the crisis, but neither President Grover Cleveland nor President William McKinley had taken the bait thus far.

With the heavy loss of life that accompanied the sinking, “Remember the Maine” became a national obsession. Although Spain had very little to gain from sinking an American warship, whereas Cuban rebels had much to gain in order to bring the United States actively to their cause, the public outcry was directed against Spain. The Spanish government previously had offered to change its military tactics in Cuba and to allow Cubans limited home rule. The offer now was to grant an armistice to the insurgents. The American ambassador in Spain believed that the Spanish government would even be willing to grant independence to Cuba, if there were no political or military attempt to humiliate Spain.

Neither the Spanish government nor McKinley wanted war. However, the latter proved unable to resist the new martial mood and the aroused jingoism in the press and Congress. On April 11, 1898, McKinley sent a message to Congress that did not directly call for war, but declared that he had “exhausted every effort” to resolve the matter and was awaiting Congress’s action. Congress declared war. A year later, McKinley observed, “But for the inflamed state of public opinion, and the fact that Congress could no longer be held in check, a peaceful solution might have been had.” He might have added that, had he been possessed of a stiffer political spine, that peaceful solution might have been had, as well.

The “splendid little war,” in the words of the soon-to-be Secretary of State, John Hay, was exceedingly popular and resulted in an overwhelming and relatively easy American victory. Only 289 were killed in action, although, due to poor hygienic conditions, many more died from disease. Psychologically, it proved cathartic for Americans after the national trauma of the Civil War. One symbolic example of the new unity forged by the war with Spain was that Joe Wheeler and Fitzhugh Lee, former Confederate generals, were generals in the U.S. Army.

Spain signed a preliminary peace treaty in August. The treaty called for the surrender of Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Guam. The status of the Philippines was left for final negotiations. The ultimate treaty was signed in Paris on December 10, 1898. The Philippines, wracked by insurrection, were ceded to the United States for $2 million. The administration believed that it would be militarily advantageous to have a base in the Far East to protect American interests.

The war may have been popular, but the peace was less so. The two-thirds vote needed for Senate approval of the peace treaty was a close-run matter. There was a militant group of “anti-imperialists” in the Senate who considered it a betrayal of American republicanism to engage in the same colonial expansion as the European powers. Americans had long imagined themselves to be unsullied by the corrupt motives and brutal tactics that such colonial ventures represented in their minds. McKinley, who had reluctantly agreed to the treaty, reassured himself and Americans, “No imperial designs lurk in the American mind. They are alien to American sentiment, thought, and purpose.” But, with a nod to Rudyard Kipling’s urging that Americans take on the “white man’s burden,” McKinley cast the decision in republican missionary garb, “If we can benefit those remote peoples, who will object? If in the years of the future they are established in government under law and liberty, who will regret our perils and sacrifices?”

The controversy around an “American Empire” was not new. Early American republicans like Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton, and John Marshall, among many others, had described the United States in that manner and without sarcasm. The government might be a republic in form, but the United States would be an empire in expanse, wealth, and glory. Why else acquire the vast Louisiana territory in 1803? Why else demand from Mexico that huge sparsely-settled territory west of Texas in 1846? “Westward the Course of Empire Takes Its Way,” painted Emanuel Leutze in 1861. Manifest Destiny became the aspirational slogan.

While most Americans cheered those developments, a portion of the political elite had misgivings. The Whigs opposed the annexation of Texas and the Mexican War. To many Whigs, the latter especially was merely a war of conquest and the imposition of American rule against the inhabitants’ wishes. Behind the republican facade lay a more fundamental political concern. The Whigs’ main political power was in the North, but the new territory likely would be settled by Southerners and increase the power of the Democrats. That movement of settlers would also give slavery a new lease on life, something much reviled by most Whigs, among them a novice Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln.

Yet, by the 1890s, the expansion across the continent was completed. Would it stop there or move across the water to distant shores? One omen was the national debate over Hawaii that culminated in the annexation of the islands in 1898. Some opponents drew on the earlier Whig arguments and urged that, if the goal of the continental expansion was to secure enough land for two centuries to realize Jefferson’s ideal of a large American agrarian republic, the goal had been achieved. Going off-shore had no such republican fig leaf to cover its blatant colonialism.

Other opponents emphasized the folly of nation-building and trying to graft Western values and American republicanism onto alien cultures who neither wanted them nor were sufficiently politically sophisticated to make them work. They took their cue from John C. Calhoun, who, in 1848, had opposed the fanciful proposal to annex all of Mexico, “We make a great mistake in supposing that all people are capable of self-government. Acting under that impression, many are anxious to force free Governments on all the people of this continent, and over the world, if they had the power…. It is a sad delusion. None but a people advanced to a high state of moral and intellectual excellence are capable in a civilized condition, of forming and maintaining free Governments ….”

With peace at hand, the focus shifted to political and legal concerns. The question became whether or not the Constitution applied to these new territories ex proprio vigore: “Does the Constitution follow the flag?” Neither President McKinley nor Congress had a concrete policy. The Constitution, having been formed by thirteen states, along the eastern slice of a vast continent, was unclear. The Articles of Confederation had provided for the admission of Canada and other British colonies, such as the West Indies, but that document was moot. The matter was left to the judiciary, and the Supreme Court provided a settlement of sorts in a series of cases over two decades called the Insular Cases.

Cuba was easy. Congress’s declaration of war against Spain had been clear: “The United States hereby disclaims any disposition or intention to exercise sovereignty, jurisdiction, or control over said island except for the pacification thereof, and asserts its determination, when that is accomplished, to leave the government and control of the island to its people.” In Neely v. Henkel (1901), the Court unanimously held that the Constitution did not apply to Cuba. Effectively, Cuba was already a foreign country outside the Constitution. Cuba became formally independent in 1902. In similar manner, the United States promised independence to the Philippine people, a process that took several decades due to various military exigencies. Thus, again, the Constitution did not apply there, at least not tout court, as the Court affirmed beginning in Dorr v. U.S. in 1904. That took care of the largest overseas dominions, and Americans could tentatively congratulate themselves that they were not genuine colonialists.

More muddled was the status of Puerto Rico and Guam. In Puerto Rico, social, political, and economic conditions did not promise an easy path to independence, and no such assurance was given. The territory was not deemed capable of surviving on its own. Rather, the peace treaty expressly provided that Congress would determine the political status of the inhabitants. In 1900, Congress passed the Foraker Act, which set up a civil government patterned on the old British imperial system with which Americans were familiar. The locals would elect an assembly, but the President would appoint a governor and executive council. Guam was in a similar state of dependency.

In Downes v. Bidwell (1901), the Court established the new status of Puerto Rico as neither outside nor entirely inside the United States. Unlike Hawaii or the territories that were part of Manifest Destiny, there was no clear determination that Puerto Rico was on a path to become a state and, thus, was already incorporated into the entity called the United States. It belonged to the United States, but was not part of the United States. The Constitution, on its own, applied only to states and to territory that was expected to become part of the United States. Puerto Rico was more like, but not entirely like, temporarily administered foreign territory. Congress determined the governance of that territory by statute or treaty, and, with the exception of certain “natural rights” reflected in particular provisions of the Bill of Rights, the Constitution applied only to the extent to which Congress specified.

These cases adjusted constitutional doctrine to a new political reality inaugurated by the sinking of the Maine and the war that event set in motion. The United States no longer looked inward to settle its own large territory and to resolve domestic political issues relating to the nature of the union. Rather, the country was looking beyond its shores and was emerging as a world power. That metamorphosis would take a couple of generations and two world wars to complete, the last of which triggered by another surprise attack on American warships.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!