October 26, 1825: The Erie Canal is Completed

In 1817, construction on the Erie Canal began, opening in October of 1825. Initially a 363-mile waterway, 40 feet wide and four feet deep, it connected the Great Lakes and Atlantic Ocean flowing from the Hudson River at Albany to Lake Erie at Buffalo, New York. The canal increased transportation of bulk commercial goods at a much lower cost, widely expanded agricultural development, and brought settlers into surrounding states as the free flow of goods to the stretches of Northwest Territory were availed through the Appalachian Mountains.

On Friday, July 13, 1787, “James Madison’s Gang,” otherwise known as the Constitutional Convention, approved a motion stating that until completion of the first census, showing exactly how many residents each state contained, direct taxes to the states would be proportioned according to the number of representatives the state had been assigned in Congress. A short time later, Gouverneur Morris of Pennsylvania and Pierce Butler of South Carolina had a rather heated exchange over the issue of slavery and how to account for slaves in determining the state’s representation.

That same day, ninety-five miles to the northeast in New York City, the Confederation Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance, creating the Northwest Territory and opening a significant new portion of the country to rapid settlement. The territory would go on to produce 5 new states and, more importantly to our story, produce tons and tons of grain in its fertile Ohio Valley. At the time, the only practical route to bring this produce to world markets was the long, 1,513 miles, voyage down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers from Cincinnati, Ohio to New Orleans, a voyage that could take weeks and was quite expensive. A cheaper, more efficient method had to be found.

The idea of a canal that would tie the western settlements of the country to the ports on the East Coast had been discussed as early as 1724. Now that those settlements were becoming economically important, talk resumed in earnest.

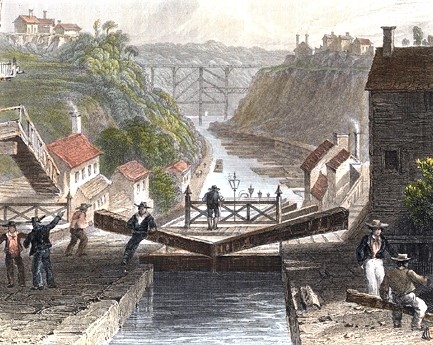

The first problem encountered was geography. The most logical western route for a canal was from the east end of Lake Erie at Buffalo, to Albany, New York on the Hudson River, but Lake Erie sits 570 feet above sea level. Descending eastward from the lake to the Hudson River would be relatively easy, but canals had to allow traffic in both directions. Ascending 570 feet in elevation on the westbound trip meant one thing: locks and lots of them. Lock technology at the time could only provide a lift of 12 feet. It was soon determined that fifty locks would be required along the 363 mile canal. Given the technology of the time, such a canal would be exorbitantly expensive to build; the cost was barely imaginable. President Jefferson called the idea “little short of madness” and rejected any involvement of the federal government. This left it up to the State of New York and private investors. The project would not get any relief with a change of Presidents. On March 3, 1817, President James Madison vetoed “An act to set apart and pledge certain funds for internal improvements.” In his veto message, Madison wrote he was “constrained by the insuperable difficulty [he felt] in reconciling the bill with the Constitution of the United States.”

“The legislative powers vested in Congress are specified and enumerated in the eighth section of the first article of the Constitution, and it does not appear that the power proposed to be exercised by the bill is among the enumerated powers, or that it falls by any just interpretation within the power to make laws necessary and proper for carrying into execution those or other powers vested by the Constitution in the Government of the United States…

“The power to regulate commerce among the several States” can not include a power to construct roads and canals, and to improve the navigation of water courses…”

Once again, no help would come from the federal government.

Two different routes were considered: a southern one which would be shorter but present more challenging topography and a northern route which was longer but presented much easier terrain to deal with. The northern route was selected.

Estimates of the workers involved in building the canal vary widely, from 50,000 to 3,000 workers. A thousand men reportedly died building Governor DeWitt Clinton, “Clinton’s Folly” — the majority of them due to canal wall collapses, drowning, careless use of gunpowder and disease. Men dug, by hand, the 4-foot-deep by 40-foot-wide canal, aided occasionally by horses or oxen, explosives, and tree-stump-pulling machines. They were paid 50 cents a day, about $12 a month, and were sometimes provided meals and a place to sleep. The sides of the canal were lined with stone set in clay. The project required the importation of hundreds of skilled German stonemasons.

The gamble paid off. Once the canal opened, tolls charged to barges paid off the construction debt within ten years. From 1825 to 1882, tolls generated $121 million, four times what it cost to operate the canal. When completed in 1825, it was the second longest canal in the world.

The Erie Canal’s early commercial success, combined with the engineering knowledge gained in building it, encouraged the construction of other canals across the United States. None, however, would come close to repeating the success of the Erie. Other projects became enmeshed in politics. They became more and more expensive to build and maintain. Many canals had to be closed in the winter, yet goods still needed to get to market, whatever the cost. Railroads soon began offering competitive rates.

But the Erie Canal left its mark. New York City is today the business and financial capital of America due largely to the success of the Erie Canal.

Today, the Erie Canal is a modest tourist attraction. Cheaper means are available to move cargo. You can still take a leisurely trip via small boat from the Great Lakes to the Hudson and beyond. But so can certain species of fish, mollusks and plants use the canal and its boat traffic to make their way from the Great Lakes to “invade” New York’s inland lakes and streams, the Hudson River and New York harbor.

In 2017, Governor Andrew M. Cuomo established a “Reimagining the Canal task force” to determine the canal’s future. Addressing the environmental damage caused by invasive animal and plant life, the task force recommended permanently closing and draining portions of the canal in Rochester and Rome.

I grew up in Erie, Pennsylvania an hour’s drive from the terminus of the canal at Buffalo and I still recall the family visit we took to see it. My young brain didn’t really comprehend the labor and hardship faced by those thousands of workers over those eight years of construction. But now I can marvel at their ingenuity and perseverance in the face of amazing engineering challenges – a testament to the American Spirit.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!