Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Why Government?

Thomas Jefferson said it most succinctly: “to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men.” We could end this discussion right there – the “appropriate role and purpose of government” is the “security, the protection of unalienable rights,” but we all know there is more to the story.

Americans today are losing touch with the concept of God-given, unalienable rights, some in fact firmly reject the idea, even the existence of such rights, believing instead that government is not only the protector of our rights, but also their source. America’s Founders rejected this concept out of hand. As Jefferson clearly stated, we “are endowed by [our] creator with certain unalienable rights.” He made a similar observation two years prior in his Summary View of the Rights of British America[i] and later in his 1785 Notes on the State of Virginia.[ii]

The Source of Rights

Today, however, when someone speaks of “natural law” or “natural rights” they should be asked to clarify whether they are referring to God-given natural rights or rights which accrue to humans “naturally” through a social contract or “the nature of things.” The use of the adjective “inherent” in describing rights, as George Mason did in the 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights,[iii] lends itself to two different interpretations, the rights are either uniquely inherent to humans as creations of God or are uniquely inherent to humans as the apex species of evolution. Given this, I prefer “unalienable” to “inherent.”

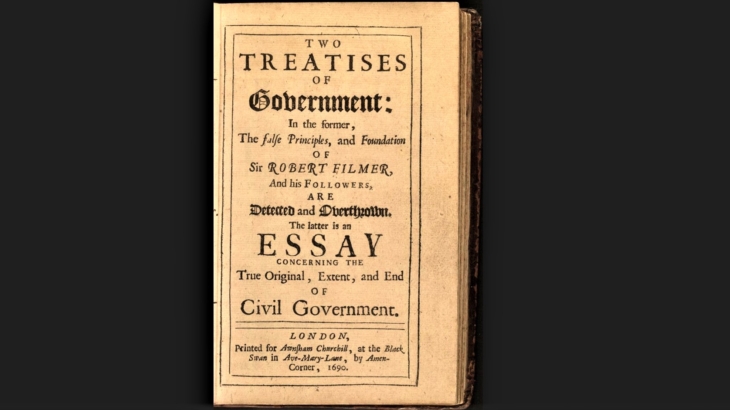

Though a Christian (he authored “The Truth of the Christian Religion”), the Dutch political philosopher Hugo Grotius[iv] promoted the idea (borrowed from Cicero and others) that natural law was created by the natural order and was not, or at least not necessarily a creation of God. Natural law did not require God’s revelation but could be discovered simply and solely through human reason. While America’s Founders knew of and respected Grotius, particularly his famous 1625 On the Law of War and Peace (De Jure Belli ac Pacis), as we see will in the following quotations, they held to a theistic source for both natural law and natural rights.

But even America’s leaders had to remind their fellow citizens of this from time to time. Writing in reply to an essay from “The Farmer,”[v] Alexander Hamilton explained:

“The fundamental source of all your errors, sophisms[vi] and false reasonings is a total ignorance of the natural rights of mankind. Were you once to become acquainted with these, you could never entertain a thought, that all men are not, by nature, entitled to a parity of privileges. You would be convinced, that natural liberty is a gift of the beneficent Creator to the whole human race, and that civil liberty is founded in that; and cannot be wrested from any people, without the most manifest violation of justice. Civil liberty is only natural liberty, modified and secured by the sanctions of civil society. It is not a thing, in its own nature, precarious and dependent on human will and caprice; but it is conformable to the constitution of man, as well as necessary to the well-being of society…”To grant that there is a supreme intelligence who rules the world and has established laws to regulate the actions of his creatures; and still to assert that man, in a state of nature, may be considered as perfectly free from all restraints of law and government, appears to a common understanding altogether irreconcilable. Good and wise men, in all ages, have embraced a very dissimilar theory. They have supposed that the deity, from the relations we stand in to himself and to each other, has constituted an eternal and immutable law, which is indispensably obligatory upon all mankind, prior to any human institution whatever. This is what is called the law of nature . . . . Upon this law depend the natural rights of mankind: the Supreme Being gave existence to man, together with the means of preserving and beatifying that existence. He endowed him with rational faculties, by the help of which, to discern and pursue such things, as were consistent with his duty and interest, and invested him with an inviolable right to personal liberty, and personal safety . . . . The Sacred Rights of Mankind are not to be rummaged for, among old parchments, or musty records. They are written, as with a sun beam, in the whole volume of human nature, by the Hand of the Divinity itself; and can never be erased or obscured by mortal power.”[vii]

Human beings have natural, unalienable rights which are incapable of being “be erased or obscured” by any act of man or government.

In his 1765 Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law, John Adams insisted that our rights were “derived from the great Legislator of the universe.”

Virginian lawyer George Mason, arguing in the 1772 case of Robin v. Hardaway, (1 Jefferson 109) affirmed that:

“The laws of nature are the laws of God: A legislature must not obstruct our obedience to him from whose punishments they cannot protect us. All human constitutions which contradict His laws, we are in conscience bound to disobey. Such have been the adjudications of our courts of justice.” [viii]

Other American Founders, such as John Dickinson, expressed similar views:

“Kings or parliaments could not give the rights essential to happiness… We claim them from a higher source – from the King of kings, and Lord of all the earth. They are not annexed to us by parchments and seals. They are created in us by the decrees of Providence, which establish the laws of our nature. They are born with us; exist with us; and cannot be taken from us by any human power without taking our lives. In short, they are founded on the immutable maxims of reason and justice.”[ix]

Dickinson was an intriguing man, largely overlooked today. Born into a family with long-standing ties to the Quaker religion, Dickinson received an education in the law at the Middle Temple, London, before setting up his practice near Philadelphia. He inherited land holdings in both Pennsylvania and Delaware and became one of the richest men in both states.[x] In 1776, Dickinson represented Pennsylvania at the Continental Congress as it considered independence. His Quaker roots kept him from openly voting for independence (and inevitable war), so on the fateful day of July 2, 1776, Dickinson (along with Robert Morris) “absented himself” to give the Pennsylvania delegation a majority in favor of Virginia’s resolution for independence. Once the resolution for independence passed, Dickinson similarly refused to vote in favor of Jefferson’s Declaration, a decision which then forced his resignation from the Pennsylvania delegation. Once out of the Congress, Dickinson surprisingly joined the Pennsylvania militia as a Brigadier General, becoming one of only two members of the First Continental Congress who actively took up arms during the war. Dickinson capped his long public service career by representing Delaware at the Constitutional Convention.

In this statement on natural rights, Dickinson repeats familiar themes: rights originating with a Creator God, resulting from God’s natural law, and which “cannot be taken from us by any human power.”

James Wilson, one of six men who signed both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, after calling God “the promulgator as well as the author of natural law,” observed in his famous 1790 Lectures on Law:

“I here close my examination into those natural rights, which, in my humble opinion, it is the business of civil government to protect, and not to subvert, and the exercise of which it is the duty of civil government to enlarge, and not to restrain. I go farther; and now proceed to show, that in peculiar instances, in which those rights can receive neither protection nor reparation from civil government, they are, notwithstanding its institution, entitled still to that defence, and to those methods of recovery, which are justified and demanded in a state of nature.”[xi]

To protect and enlarge our natural rights, this becomes the “business” of civil government, or at least one of the responsibilities or duties of government.

The History of Rights (much abridged)

Rights, and the security thereof, had gradually become a central focus of Englishmen as they wrestled with two oftentimes opposing concepts: the divine (i.e., God-endorsed) right of kings on the one hand, and the unalienable, God-given rights of individuals on the other hand. Magna Carta became a waypoint in this investigation; forcing King John to subordinate his divine right and accept responsibility for protecting certain individual rights, including due process of law and trial by jury.

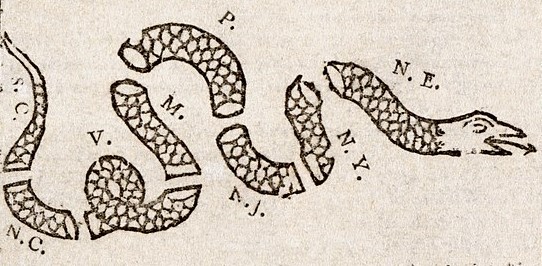

Magna Carta was soon ignored, but was eventually replaced by newer versions. In the 17th century, Magna Carta’s rights were supplemented by Parliament’s Petition of Right (1628) and the English Bill of Rights (1689). This growing focus on natural rights accompanied America’s settlers as they sailed for the colonies, being encapsulated in the first colonial charters as “liberties, franchises and immunities”[xii] of Englishmen. From there, rights were expanded and reinforced, expounded in a host of colonial documents, beginning with the Mayflower Compact and ending one hundred and seventy-one years later with the Constitution’s Bill of Rights. Over this period, the colonists seldom passed up an opportunity to reiterate their essential rights. A partial list:

1620 – Mayflower Compact (Plymouth)

1636 – Code of Law (Plymouth)

1639 – Fundamental Orders (Connecticut)

1639 – Act for the Liberties of the People (Maryland)

1641 – Body of Liberties (Massachusetts)

1677 – Declaration of the People (Virginia)

1701 – Charter of Privileges (Pennsylvania)

1763 – The Rights of the British Colonies Asserted and Proved (James Otis)

1764 – The Rights of Colonies Examined (Stephen Hopkins)

1765 – Declaration of Rights and Grievances (Stamp Act Congress)

1766 – An Inquiry into the Rights of The British Colonies (Richard Bland)

1772 – The Rights of the Colonists (Samuel Adams)

1774 – A Summary View of the Rights of British America (Thomas Jefferson)

1774 – Declaration and Resolves (1st Continental Congress)

1775 – Declaration on the Causes of Taking Up Arms (2nd Congress)

1776 – (January) Bill of Rights (New Hampshire Convention)

1776 – (June) Declaration of Rights (Virginia)

1776 – (July) Declaration of Independence (2nd Continental Congress)

1776 – (July) Declaration of Rights (Pennsylvania)

1776 – (September) Declaration of Rights (Delaware)

1780 – Declaration of Rights (Massachusetts)

1788 – Declaration of Rights (North Carolina)

1790 – Of the Natural Rights of Individuals -Lectures on Law (James Wilson)

1791 – The U.S. Bill of Rights

Natural law and the natural rights which spring from them are enjoying a resurgence in popularity of late, thanks to the scholarly work of men like John Finnis in Natural Law and Natural Rights (Clarendon Law Series, 2nd Edition; J. Budziszewski in Written on the Heart: The Case for Natural Law; Hadley Arkes in Mere Natural Law: Originalism and the Anchoring Truths of the Constitution; and others. As John Horvat explains, “the growing acceptance of natural law theory among frustrated Americans is shaking the legal field.”[xiii] This resurgence within the legal and scholarly communities appears to terrify some, however, natural law and natural rights are still ignored or misunderstood by the vast majority of Americans.

The Extent of Natural Rights

There is no known “inventory” of natural rights, at least none that all political philosophers or natural rights expositors over the millennia have agreed upon. The Founders knew of course of the Ten Commandments, which form the core of “the laws of Nature’s God.” If God commands “thou shalt not steal” it seems reasonable to derive from that “a right to acquire and retain property.” “Thou shalt not murder” denotes a “right to the preservation of one’s life.” But no Founding Father appears to have attempted an enumeration of all natural rights. Indeed, as James Iredell explained at the 1788 North Carolina Ratifying Convention, such an enumeration, if used as the basis for a Bill of Rights:

“…would not only be useless, but dangerous, … it would be implying, in the strongest manner, that every right not included in the [enumeration] might be impaired by the government without usurpation; and it would be impossible to enumerate every one. Let any one make what collection or enumeration of rights he pleases, I will immediately mention twenty or thirty more rights not contained in it.”[xiv]

But a useful list of those essential rights the Founders collectively supported can nevertheless be gleaned from their writings. As Chester James Antieau explains:[xv] “the natural rights on which there was the largest agreement and the greatest significance were … freedom of conscience and religion, life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, property, the right to govern and tax themselves, and freedom of communication.”

Some Founders also supported rights derived from the common law, such as the right to trial by jury, and freedom from warrantless searches, but such rights cannot be denominated as “natural” rights since they would have no rational basis in a hypothetical state of nature.

How Should Rights Be Secured?

The next question we must consider is: how should the government fulfill its responsibility of protecting our unalienable rights? Is a Bill of Rights necessary, or even appropriate?

James Madison and other Founders considered the Constitution itself to be a “bill of rights.” A constitution of limited and enumerated powers, carefully drawn, will protect individual rights by not providing the new government with the power or authority necessary to infringe on those rights. “For why declare that things shall not be done which there is no power to do?” wrote Alexander Hamilton in Federalist 84.[xvi] While the Framers certainly felt they had created a limited power document, replete with checks and balances, history has shown the ambiguity of language to be the Framers’ downfall. The Anti-federalists saw “loopholes”; for instance, the power given the Supreme Court would allow the court to “mould the government, into almost any shape they please.”[xvii] The Anti-federalists fumed over the absence of a Bill of Rights, “would it have consumed too much paper?” scowled Patrick Henry. When sent a copy of the Constitution to review, Jefferson replied by gently chiding his friend: “A bill of rights is what the people are entitled to against every government on earth, general or particular; and what no just government should refuse, or rest on inferences.” [xviii]And so a reluctant James Madison agreed to single-handedly champion the project.

The initial draft he submitted to Congress, borrowing heavily from the Virginia Declaration of Rights, contained several protections which did not survive the House and Senate “wordsmithing.” Madison’s treasured “rights of conscience” didn’t even make it through the House Committee on which Madison himself sat!. Despite these setbacks, Madison persisted and the document was finally sent to the states for ratification, achieving that on December 15, 1791, with Virginia’s acceptance. But would a Bill of Rights be enough?

In an October 1788 letter to Thomas Jefferson, Madison had warned that even a Bill of Rights might not be sufficient: “Repeated violations of these parchment barriers have been committed by overbearing majorities in every State. In Virginia I have seen the bill of rights violated in every instance where it has been opposed to a popular current.”[xix] “Tyranny of the majority,” the primary reason the Founders’ abhorred democracy. But infringements of rights do not require a majority, with the help of government even a minority can prevail.

When Governments Become Corrupted

Americans have recently witnessed how a government can be enticed to infringe upon our unalienable rights by a “popular current” arising from even a small minority faction. The revelation that officials in the Executive branch of the federal government colluded with media companies to silence the public expression of viewpoints they did not agree with shocks us, it is reminiscent of the Communist regimes under Stalin and Mao, not to mention the authoritarian governments in present-day Russia and China.

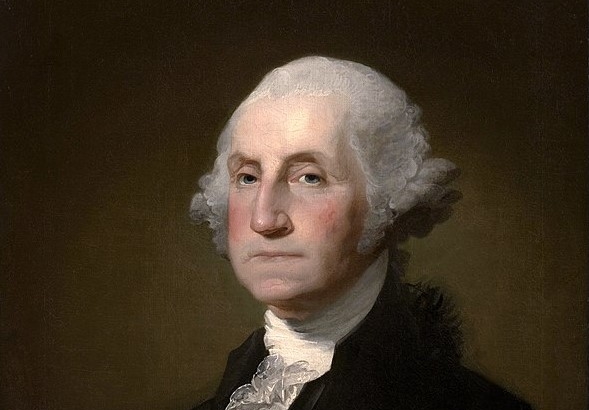

Jefferson believed that: “The republican is the only form of government which is not eternally at open or secret war with the rights of mankind.”[xx]

The Americans are the ultimate sovereigns in their republican form of government; government is their servant, not the reverse. Unfortunately, the American people, by and large, have abandoned the Founders’ view of both law and government.

If there is any good news here it is that at least some Americans, those who understand the societal sea-change being forced upon them, are willing to fight for protection of their unalienable rights. Welcome assistance comes from the present Supreme Court, which is currently staffed with a majority of justices who share an originalist and therefore Founders’ view of rights. But our trust in a temporary majority of originalist justices should be cautioned by the realization that future courts may not be so favorably apportioned. As Jefferson reminds us: “In questions of power, then, let no more be heard of confidence in man, but bind him down from mischief by the chains of the Constitution.”[xxi]

So, it is to the Bill of Rights itself we must turn; is its language sufficient or too open to interpretation? Should we consider the words of the original Bill of Rights as unamendable, or should we be willing to clarify ambiguous 18th century language? Are we to accept our society’s present worldview confusion as inevitable or should we work to correct it?

These are the sort of questions we should be asking, and debating.

In his 1967 Inaugural Address, the great Ronald Reagan cautioned:

“Freedom is a fragile thing and it’s never more than one generation away from extinction. It is not ours by way of inheritance; it must be fought for and defended constantly by each generation, for it comes only once to a people. And those in world history who have known freedom and then lost it have never known it again.”[xxii]

If we want to continue to enjoy our natural, unalienable, God-given rights, and we wish our posterity to be likewise blessed, we must be prepared to fight for and defend them.

I will conclude with the words of Founder John Jay, first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court under the new Constitution, who in 1777, while instructing (charging) a New York grand jury, reminded us:

“Every member of the State ought diligently to read and to study the constitution of his country and teach the rising generation to be free. By knowing their rights, they will sooner perceive when they are violated, and be the better prepared to defend and assert them.”[xxiii]

Note that, for (at that time) Judge Jay, reading the Constitution is not sufficient, it should also be studied, and diligently so. The goal, of course, lies not simply in the reading and studying; the goal is to pass along what you have learned to the next generation of Americans. Even then, the project is not complete; the rising generation requires this knowledge to be better equipped to defend and assert their rights, thus, hopefully, perpetuating a society of freedom and liberty.

John Jay would be proud of the commendable work Constituting America accomplishes in pursuing his charge.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at

gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter @constitutionled.

[i] https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/jeffsumm.asp.

[ii] https://docsouth.unc.edu/southlit/jefferson/jefferson.html.

[iii] “That all men are by nature equally free and independent and have certain inherent rights, of which, when they enter into a state of society, they cannot, by any compact, deprive or divest their posterity; namely, the enjoyment of life and liberty, with the means of acquiring and possessing property, and pursuing and obtaining happiness and safety.”

[iv] A latinizing of his given name: “Huig van Groot.”

[v] Hamilton was replying to a series of essays, appearing from November 1774 to January 1775, written by “A W. Farmer, (loyalist Bishop Samuel Seabury, the first American Episcopal bishop), who had set out “to detect and expose the false, arbitrary, and tyrannical PRINCIPLES upon which the [Continental] Congress acted, and to point out their fatal tendency to the interests and liberties of the colonies.” To see the arguments Hamilton is “refuting,” the “Farmer’s” letters can be accessed at: http://anglicanhistory.org/usa/seabury/farmer/.

[vi] Sophisms: specious arguments for displaying ingenuity in reasoning or for deceiving someone. Dictionary.com.

[vii] Alexander Hamilton, The Farmer Refuted, February 23, 1775, New York.

[viii] https://cite.case.law/jefferson/1/109/.

[ix] John Dickinson, An Address to the Committee of Correspondence in Barbados, 1766.

[x] Interestingly, for a short period of time (November 1782-January 1783) Dickinson served as the President of both states.

[xi] http://www.nlnrac.org/node/241.

[xii] 1606 First Virginia Charter, at: https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/first-charter-of-virginia-1606/.

[xiii] https://www.tfp.org/why-the-left-hates-and-is-terrified-by-natural-law/.

[xiv] https://docsouth.unc.edu/nc/conv1788/conv1788.html, p. 192.

[xv] Chester James Antieau, Natural Rights And The Founding Fathers-The Virginians, 17 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 43 (1960), http://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol17/iss1/4.

[xvi] https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/fed84.asp.

[xvii] Brutus XI, in The Complete Anti-Federalist, Herbert J. Storing, ed., (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1981) Volume Two, Part 2, 417-422.

[xviii] Thomas Jefferson, Letter to James Madison, December 20, 1787.

[xix] https://press-pubs.uchicago.edu/founders/documents/v1ch14s47.html.

[xx] Letter to William Hunter, 11 March 1790., at https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-16-02-0130.

[xxi] Thomas Jefferson, in a draft of the Kentucky Resolutions of 1798.

[xxii] This is the version Reagan uttered during his Inaugural Address as President on January 5, 1967, not the more familiar and edited version published afterwards. See: https://www.reaganlibrary.gov/archives/speech/january-5-1967-inaugural-address-public-ceremony.

[xxiii] The Correspondence and Public Papers of John Jay, ed. Henry P. Johnston, A.M. (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1890-93). Vol. 1 (1763-1781), p. 164., accessed at https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/johnston-the-correspondence-and-public-papers-of-john-jay-vol-1-1763-1781?html=true.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Kevin Portteus is Professor of Politics, Director of American Studies, and the Lawrence Fertig Chair in Politics at Hillsdale College.

Kevin Portteus is Professor of Politics, Director of American Studies, and the Lawrence Fertig Chair in Politics at Hillsdale College.

Amanda Hughes serves as 90-Day Study Director for Constituting America. She is author of a book on faith and voting, Who Wants to Be Free? (WestBow Press). She is a story contributor for the anthologies Loving Moments and Moments with Billy Graham (Grace Publishing). She served as editor of her father’s book, Adventures, Wit & Wisdom: The Life & Times of Charlie Hughes (WestBow Press). Amanda received her B.A. from Texas State University and her M.A. from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Amanda Hughes serves as 90-Day Study Director for Constituting America. She is author of a book on faith and voting, Who Wants to Be Free? (WestBow Press). She is a story contributor for the anthologies Loving Moments and Moments with Billy Graham (Grace Publishing). She served as editor of her father’s book, Adventures, Wit & Wisdom: The Life & Times of Charlie Hughes (WestBow Press). Amanda received her B.A. from Texas State University and her M.A. from Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

George Landrith is the President of Frontiers of Freedom.

George Landrith is the President of Frontiers of Freedom.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, a Fellow with Constituting America, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, a Fellow with Constituting America, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Patrick M. Garry is professor of law at the University of South Dakota. He is author of Limited Government and the Bill of Rights and The False Promise of Big Government: How Washington Helps the Rich and Hurts the Poor.

Patrick M. Garry is professor of law at the University of South Dakota. He is author of Limited Government and the Bill of Rights and The False Promise of Big Government: How Washington Helps the Rich and Hurts the Poor.

Stephen Tootle is a Professor of History at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia, California and Honored Visiting Graduate Faculty in History and Government at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio. His writings have appeared in National Review, Presidential Studies Quarterly, The Claremont Review of Books, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, and other publications. He gives talks on politics and political history for the Ashbrook Center and the Bill of Rights Institute and is the co-host of The Paper Trail Podcast, a weekly public affairs podcast published by the Sun-Gazette.

Stephen Tootle is a Professor of History at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia, California and Honored Visiting Graduate Faculty in History and Government at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio. His writings have appeared in National Review, Presidential Studies Quarterly, The Claremont Review of Books, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, and other publications. He gives talks on politics and political history for the Ashbrook Center and the Bill of Rights Institute and is the co-host of The Paper Trail Podcast, a weekly public affairs podcast published by the Sun-Gazette.

James C. Clinger, Ph.D., is an emeritus professor of political science at Murray State University. His teaching and research has focused on state and local government, public administration, regulatory policy, and political economy. His forthcoming co-edited book is entitled Local Government Administration in Small Town America.

James C. Clinger, Ph.D., is an emeritus professor of political science at Murray State University. His teaching and research has focused on state and local government, public administration, regulatory policy, and political economy. His forthcoming co-edited book is entitled Local Government Administration in Small Town America.

Robert E. Wright is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. He is the (co)author or (co)editor of over two dozen major books, book series, and edited collections, including AIER’s The Best of Thomas Paine (2021) and Financial Exclusion (2019). He has also (co)authored numerous articles for important journals, including the American Economic Review, Business History Review, Independent Review, Journal of Private Enterprise, Review of Finance, and Southern Economic Review. Robert has taught business, economics, and policy courses at Augustana University, NYU’s Stern School of Business, Temple University, the University of Virginia, and elsewhere since taking his Ph.D. in History from SUNY Buffalo in 1997.

Robert E. Wright is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. He is the (co)author or (co)editor of over two dozen major books, book series, and edited collections, including AIER’s The Best of Thomas Paine (2021) and Financial Exclusion (2019). He has also (co)authored numerous articles for important journals, including the American Economic Review, Business History Review, Independent Review, Journal of Private Enterprise, Review of Finance, and Southern Economic Review. Robert has taught business, economics, and policy courses at Augustana University, NYU’s Stern School of Business, Temple University, the University of Virginia, and elsewhere since taking his Ph.D. in History from SUNY Buffalo in 1997.

Will Morrisey is Professor Emeritus of Politics at Hillsdale College, editor and publisher of Will Morrisey Reviews, an online book review publication.

Will Morrisey is Professor Emeritus of Politics at Hillsdale College, editor and publisher of Will Morrisey Reviews, an online book review publication.

James P. Pinkerton worked in the White House domestic policy offices of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush and in their 1980, 1984, 1988 and 1992 presidential campaigns. In 2008, he served as a senior adviser to Mike Huckabee’s presidential campaign. From 1996 to 2016, he was a Contributor to the Fox News Channel. A frequent contributor to Breitbart, The Daily Caller, and The American Conservative, he is a senior fellow at the America First Policy Institute. He is finishing a book on directional investment.

James P. Pinkerton worked in the White House domestic policy offices of Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush and in their 1980, 1984, 1988 and 1992 presidential campaigns. In 2008, he served as a senior adviser to Mike Huckabee’s presidential campaign. From 1996 to 2016, he was a Contributor to the Fox News Channel. A frequent contributor to Breitbart, The Daily Caller, and The American Conservative, he is a senior fellow at the America First Policy Institute. He is finishing a book on directional investment.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg

J. Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird.

J. Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird.

Tara Ross

Tara Ross

James S. Humphreys is a professor of United States history at Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky. He is the author of a biography of the southern historian, Francis Butler Simkins, entitled Francis Butler Simkins: A Life (2008), published by the University Press of Florida. He is also the editor of Interpreting American History: the New South (2018) and co-editor of the Interpreting American History series, published by the Kent State University Press.

James S. Humphreys is a professor of United States history at Murray State University in Murray, Kentucky. He is the author of a biography of the southern historian, Francis Butler Simkins, entitled Francis Butler Simkins: A Life (2008), published by the University Press of Florida. He is also the editor of Interpreting American History: the New South (2018) and co-editor of the Interpreting American History series, published by the Kent State University Press.

Benjamin Slomski is Assistant Professor of History and Political Science at Ashland University.

Benjamin Slomski is Assistant Professor of History and Political Science at Ashland University.

Eric C. Sands is Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at Berry College. He has written a book on Abraham Lincoln and edited a second volume on political parties. His teaching and research interests focus on constitutional law, American political thought, the founding, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and political parties.

Eric C. Sands is Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at Berry College. He has written a book on Abraham Lincoln and edited a second volume on political parties. His teaching and research interests focus on constitutional law, American political thought, the founding, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and political parties.

Ben Peterson is an assistant professor of political science at Abilene Christian University.

Ben Peterson is an assistant professor of political science at Abilene Christian University.

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Adam M. Carrington is an Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College. There, he teaches on matters of Constitutional law, American political institutions, and separation of powers. His writing has appeared in such popular forums as The Wall Street Journal, The Hill, National Review, and Washington Examiner. His book on the jurisprudence of Justice Stephen Field was published in 2017 by Lexington. Carrington received his B.A. from Ashland University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Baylor University. He lives in Hillsdale with his wife and their two daughters.

Adam M. Carrington is an Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College. There, he teaches on matters of Constitutional law, American political institutions, and separation of powers. His writing has appeared in such popular forums as The Wall Street Journal, The Hill, National Review, and Washington Examiner. His book on the jurisprudence of Justice Stephen Field was published in 2017 by Lexington. Carrington received his B.A. from Ashland University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Baylor University. He lives in Hillsdale with his wife and their two daughters.

Josh Herring is Professor of Classical Education at Thales College, where he oversees the development of the Classical Education teacher training program. He also serves as Director of Debate for the Thales Debate Network, and hosts The Optimistic Curmudgeon podcast. He tweets at @TheOptimisticC3.

Josh Herring is Professor of Classical Education at Thales College, where he oversees the development of the Classical Education teacher training program. He also serves as Director of Debate for the Thales Debate Network, and hosts The Optimistic Curmudgeon podcast. He tweets at @TheOptimisticC3.

Bob Brescia, Ed.D. of Odessa is a Teacher of Record for Ector County Independent School District, and an adjunct professor for Wilmington University. He previously served as the Executive Director for The John Ben Shepperd Public Leadership Institute and served as the Head of School for Saint Joseph Academy in Brownsville. He is a board member at Constituting America in Dallas, a member of the Odessa Information & Discussion Group, and an Advisory Board member for Odessa’s Southwest Heritage Credit Union. He is the former chairman of Basin PBS television and the American Red Cross of the Permian Basin and former president of Rotary International – Greater Odessa. He is also a monthly columnist for the American Society for Public Administration in Washington, DC. Brescia has twenty-seven years of military service as a highly decorated Airborne Ranger Cavalry soldier, NCO, and commissioned officer in the United States Army. He received a Bachelor of Arts (summa cum laude) in Civil Government from Norwich University, a Master of Science in Computer Information Systems and a Master of Arts in International Relations from Boston University – European Division, and a Doctor of Education in Executive Leadership with distinction from The George Washington University.

Bob Brescia, Ed.D. of Odessa is a Teacher of Record for Ector County Independent School District, and an adjunct professor for Wilmington University. He previously served as the Executive Director for The John Ben Shepperd Public Leadership Institute and served as the Head of School for Saint Joseph Academy in Brownsville. He is a board member at Constituting America in Dallas, a member of the Odessa Information & Discussion Group, and an Advisory Board member for Odessa’s Southwest Heritage Credit Union. He is the former chairman of Basin PBS television and the American Red Cross of the Permian Basin and former president of Rotary International – Greater Odessa. He is also a monthly columnist for the American Society for Public Administration in Washington, DC. Brescia has twenty-seven years of military service as a highly decorated Airborne Ranger Cavalry soldier, NCO, and commissioned officer in the United States Army. He received a Bachelor of Arts (summa cum laude) in Civil Government from Norwich University, a Master of Science in Computer Information Systems and a Master of Arts in International Relations from Boston University – European Division, and a Doctor of Education in Executive Leadership with distinction from The George Washington University.

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of Americana Corner. Tom is a West Point graduate, and serves on the board of trustees for the American Battlefield Trust as well as the National Council for the National Park Foundation.

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of Americana Corner. Tom is a West Point graduate, and serves on the board of trustees for the American Battlefield Trust as well as the National Council for the National Park Foundation.

Joseph M. Knippenberg is Professor of Politics at Oglethorpe University in Brookhaven, GA, where he has taught since 1985.

Joseph M. Knippenberg is Professor of Politics at Oglethorpe University in Brookhaven, GA, where he has taught since 1985. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. His studies focus on improving health outcomes through food assistance policy. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He now works as a personal trainer and works to improve health and fitness through both his work and study. Jay served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and four grandchildren.

Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. His studies focus on improving health outcomes through food assistance policy. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He now works as a personal trainer and works to improve health and fitness through both his work and study. Jay served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and four grandchildren.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.