Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Almost 250 years ago, on December 16, 1773, American colonists dressed as Mohawk Indians dumped tea into Boston Harbor protesting under a rallying cry of “No taxation without representation.” We call this the Boston Tea Party.

23 years ago, in May of 2000 Washington, D.C. changed the design of its license plates replacing the words “Discover and Celebrate” with “Taxation Without Representation.” This memorialized D.C. residents’ grievance that they have no voting representatives in Congress.

Suffice it to say, the principle of representation is an enduring opinion that is at the heart of what it means to be an American. But like many such opinions that spring from what Abraham Lincoln called “the mystic chords of memory” does anyone really know, concretely, what it means?

To understand, perhaps it helps to think about concepts of sovereignty. For the most part after the end of the Roman Republic most of Europe was ruled by kings or emperors. They ruled on a religious, revealed, and practical basis known as divine right of kings.

Derived from the Bible and history, divine right of kings relied on the authority of Abraham over his children, the authority of anointed kings beginning with Saul and David, and the authority of Caesar over Rome and its dominions. A single person embodies the sovereign for subjects, and that person’s authority comes down from divinely sanctioned anointing, according to hereditary rules and conquest.

The Scottish protested the oppressions of the English king, Edward II. In the Declaration of Arbroath, the Scottish appealed to their own divine right of kings through conquest.

“The Britons they first drove out, the Picts they utterly destroyed, and, even though very often assailed by the Norwegians, the Danes and the English, they took possession of that home with many victories and untold efforts.”

Contradictions aside, that was how most of Europe thought about the question of just government.

But did this mean they had no representation? To the contrary, when the English nobles at Runnymede in 1215 forced the king to sign the Magna Carta, representation in parliament became part of the English system of government though that system remained clearly under the notion of the divine right of kings. The French, whose monarchy was more absolute, had the Estates General, beginning in 1302 A.D. The German principalities of the Holy Roman Empire had the Imperial diet, as early as 777 A.D.

If there is any doubt about the compatibility of divine right of kings and representation note that the Mayflower Compact, organized to authorize the colonial pilgrims to frame “just and equal laws,” begins with the identification of the signers as “the loyal subjects of our dread sovereign Lord King James.”

But compatibility is not the same thing as perfection, and at some point after the Protestant Reformation, new ideas about the authority of men over their conscience in the concept of the “priesthood of every believer” [presbyterii fidelium] led to new ideas about the authority of men over their own government.

In Connecticut, in the 1600s, the Reverend Thomas Hooker established in his sermons consent as the basis of government rather than divine right of kings. “The foundation of authority is laid firstly in the free consent of people,” he propounded from the pulpit. And in 1639, he drafted the Fundamental Orders governing Windsor, Hartford and Wethersfield, the first charter government in the New World that did not appeal to the authority of a king for its basis in justice. Reverend John Wise of Massachusetts would preach and protest in 1687 against the imposition of taxation without representation. President Calvin Coolidge would later praise Reverend John Wise as an inspiration of the Declaration of Independence.

One should observe that the positions of Hooker preceded Thomas Hobbes’ theoretical writing on consent in Leviathan by more than 11 years, and John Locke’s theoretical writing on consent in Two Treatises by 50 years. Should anyone tell you the foundations of American notions of consent were dreamed up by theoreticians or first came to mind in 1776, correct them. Theory backfilled the practice and ethos that had taken root and was growing in America from the very start.

By the time the American Revolution rolled up on the English, Americans had been thinking about government and justice in terms of consent for more than 100 years. The Declaration of Independence reiterated and memorialized this, stating “Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

But consent requires renewal, and this implied that the practice of the colonists of electing their representatives would continue under the new forms of government of the new nation. Every election is a reflection of the principle of consent, which is not just compatible with consent but a microcosm of a broader conception of the universe. God chooses us; we choose our form of government; we choose to renew it through amendment of its form; we choose our representatives in our form of government.

J. Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird.

J. Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin#/media/File:Stalin_1920-1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin#/media/File:Stalin_1920-1.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:Evacuation_Day_and_Washington's_Triumphal_Entry.jpg

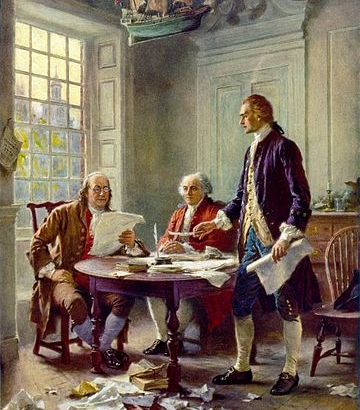

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:Evacuation_Day_and_Washington's_Triumphal_Entry.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Writing_the_Declaration_of_Independence_1776_cph.3g09904.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Writing_the_Declaration_of_Independence_1776_cph.3g09904.jpg

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.