Francis Lightfoot Lee of Virginia: Planter, House of Burgesses and Continental Congress Delegate, State Senator, and Declaration of Independence Signer

Any successful enterprise, whether it be a large business or a political movement, will have within it the widest cross section of people both leading that effort or participating within it—individuals who bring a multitude of different skills and experiences to the table in order to make certain that the endeavor will succeed. This is the true definition of “diversity,” something that looks past the cosmetic and draws on the outlook and experience of its participants.

This is certainly true with our founders, men who couldn’t have been more different than each other, despite their similarities. The authors of the Declaration of Independence: Jefferson (the principal author), John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Robert Livingston and Roger Sherman (who were all on the Continental Congress’ Declaration Committee), all brought with them unique perspectives.

These differences extended to the pair of brothers who signed the Declaration, Richard Henry Lee and Francis Lightfoot Lee, both of Virginia. The only pair of brothers to sign the Declaration of Independence, both brought with them different outlooks and temperament.

The older brother, Richard Henry Lee, with his European education and charming likeability, became a major political force in the budding liberty movement in Virginia—especially with his writing and speaking.

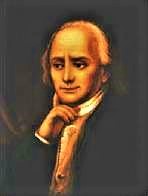

But Francis Lightfoot Lee, a planter born in 1734 in Westmoreland, Virginia, contemporarily known as Frank, the second-youngest of the Lee brothers, was a determined worker, someone who did things out of duty and a devotion to getting done whatever task lay before him. He didn’t seek the spotlight, but was seen as a tireless worker. A leader, certainly, but one who led by doing.

Political movements need both, and while much praise and attention is bestowed on the former, it is the latter which is just as important (if not more so).

It is important to note that this branch of the Lee family played a prominent role in the first three centuries of not only American history, but Virginia history as well. The Lees were what is known as “FFVs” one of the “First Families of Virginia”—the families who first settled Virginia in Colonial Times. Richard Lee I, the first Lee in Virginia, migrated to the Colonies in 1639, and served as Virginia’s Attorney General several years after his arrival. His grandson was Thomas Lee, who became Governor in 1749, and was the father of both Frank Lee and Richard Henry Lee (among the other descendants of Richard Lee I are both Gen. Robert E. Lee and President Zachary Taylor, as well as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Edward Douglass White).

Frank Lee served as a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, the elected legislature that was Colonial Virginia’s precursor to today’s House of Delegates. But from his statements, it is clear that he did so out of a duty to serve, and not to satisfy any greater political ambition. Lee wrote to his older brother at one point, when it looked like he might not get re-elected:

The people are so vexed at the little attention I have given them that they are determined it seems to dismiss me from their service, a resolution most pleasing to me, for it is so very inconvenient to me that nothing should induce me to take a poll, but a repeated promise to my friends there, enforced by those here who consider me as a staunch friend to Liberty.

Lee was focused on achieving the cause of liberty for the American Colonies, as he (like others) had grown both frustrated and dismayed by the increasing mistreatment of the Colonial Citizens by the British Crown.

He continued to serve and was eventually sent as a delegate to the Continental Congress—and John Adams remarked at the constancy of both Lee brothers who were in service together.

Frank Lee signed the Declaration and continued to serve as a Delegate to the Continental Congress, but he grew increasingly frustrated with the ambition and mismanagement of those around him. He wrote to Richard Henry Lee, his brother, again, saying:

I am as heartily tired of the knavery and stupidity of the generality of mankind as you can be; but it is our duty to stem the Current, as much as we can and to do all the service in our power, to our Country and our friends. The consciousness of having done so, will be the greatest of all rewards… [W]e may give a fair opportunity to succeeding Patriots, of making their Country flourishing and happy, but this must be the work of Peace.

He returned to Virginia following his service in the Continental Congress and served as a member of the Virginia State Senate. He retired from public and political life in 1785, having seen his deliberate “work of Peace” achieve the end he so desired. He and his wife died within one week of each other in 1797.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here for Previous Essay

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!