Essay 73 – Guest Essayist: Tony Williams

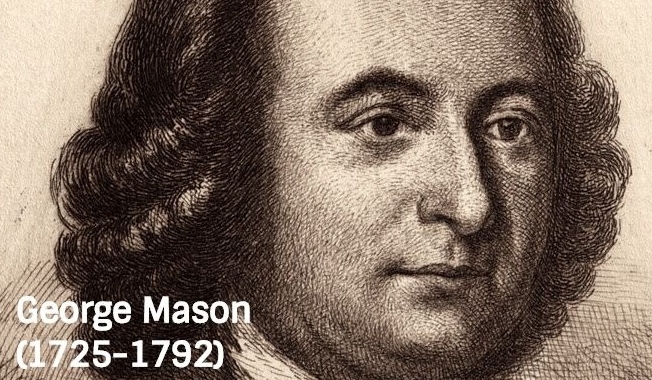

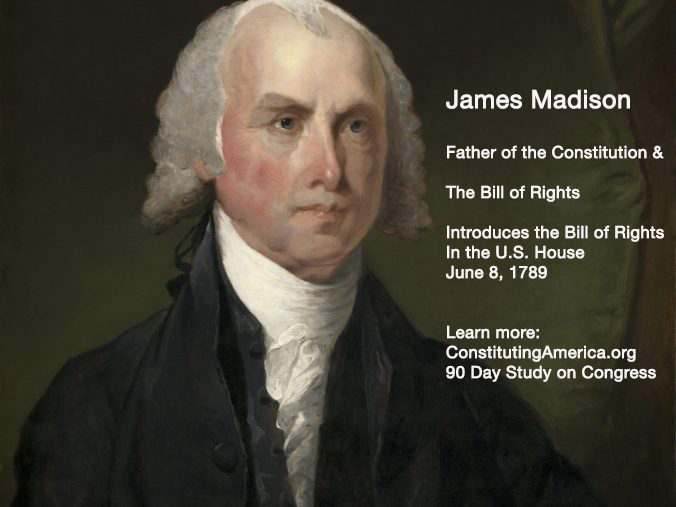

Colonial Virginia was a hierarchal society in which wealthy, slave owning planters provided political and civil leadership. Their financial independence gave them the leisure to serve in the House of Burgesses, local offices such as the militia, and Anglican parishes as vestrymen, to name a few. These planter-statesmen were the leaders of the patriot resistance movement to British tyranny in the 1760s and 1770s: George Washington, James Madison, Patrick Henry, Richard Henry Lee, and Thomas Jefferson.

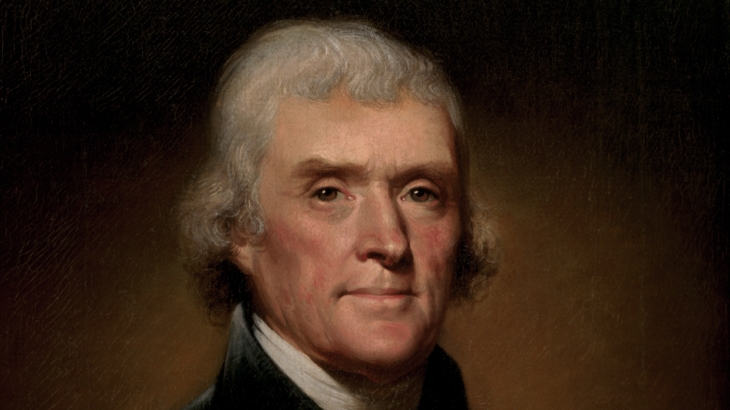

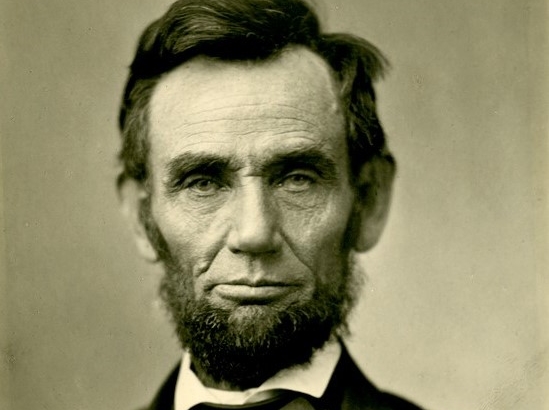

On April 13, 1743, Jefferson was born to Peter and Jane at Shadwell Plantation on the Virginia frontier. His father was a planter-statesman who passed away in 1757, leaving Thomas and his brother significant landholdings. Jefferson was destined to become a planter-statesman in his own right, though the imperial crisis and American Revolution would provide him an opportunity for greatness on a world stage as a founder and lawgiver.

In 1825, Thomas Jefferson wrote to his friend, Henry Lee, reflecting on the meaning of the Declaration of Independence. He disclaimed originality in the ideas that shaped the Declaration of Independence.

This was the object of the Declaration of Independence. Not to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent…it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion. All its authority rests then on the harmonizing sentiments of the day, whether expressed in conversation, in letters, printed essays, or in the elementary books of public right, as Aristotle, Cicero, Locke, Sidney, &c. ….”

Jefferson disclaimer to any originality in writing about the principles of natural rights republicanism in the Declaration of Independence was based upon the “harmonizing sentiments of the day” circulating in colonial newspapers, pamphlets, taverns, and colonial legislatures.

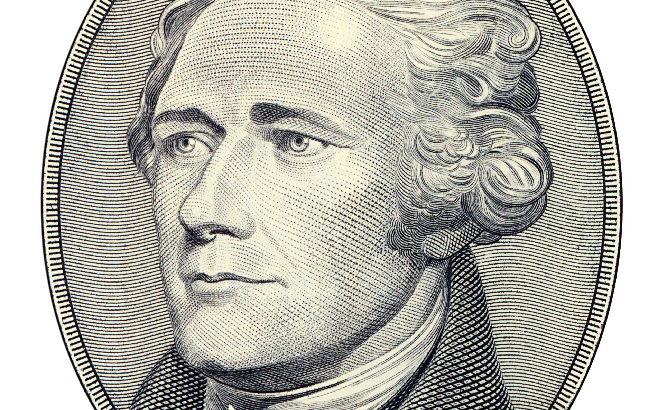

The “harmonizing sentiments” of the 1760s and 1770s supported a natural law opposition to British tyranny in the American colonies. James Otis was one of the earliest proponents of natural law resistance. In 1764, he wrote, “Should an act of Parliament be against any of his natural laws, which are immutably true, their declaration would be contrary to eternal truth, equity, and justice, and consequently void.” The speeches of Patrick Henry, the debates in the House of Burgesses and Continental Congresses, and the pamphlets of John Dickinson, Alexander Hamilton, and Thomas Paine expressed many of the same natural rights sentiments.

Jefferson also discovered these “harmonizing sentiments” during his classical education and in the books he read. He studied with Rev. William Douglas and Rev. James Maury. They provided young Jefferson with a rigorous classical education. He studied Latin and Greek, and read the poetry of Horace and Virgil, the Roman historians, and the political ideas of Cicero and Aristotle. He derived much of his thinking about natural law and political principles from these sources.

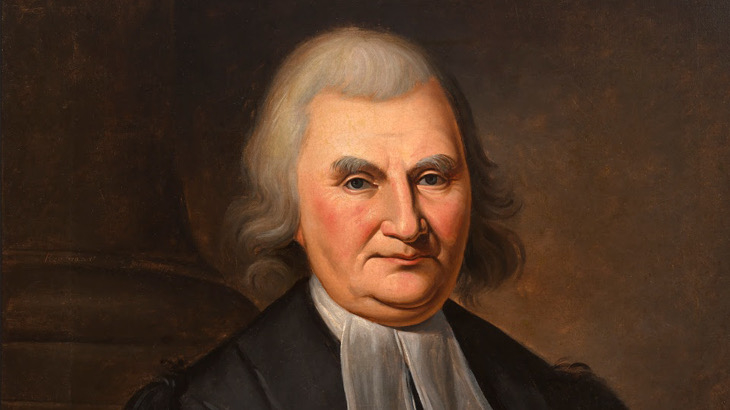

During his time with these tutors, Jefferson did not neglect his study of modern languages and political thought. He learned French and began his reading in the thinkers of the Enlightenment such as John Locke. He continued his study of the Enlightenment, especially the ideas of the Scottish Enlightenment, when he went to the College of William and Mary. While he was at college, he studied and read English law with George Wythe.

Jefferson said of his beloved teacher, Wythe, “No man ever left behind a character more venerated than George Wythe…and, devoted as he was to liberty, and the natural and equal rights of man, he might truly be called the Cato of his country.”

Jefferson’s education thus had a strong foundation in the study of natural law and popular government from a variety of traditions: ancient Greece and Rome, the English tradition, the ideas of John Locke and other Enlightenment thinkers combined with Protestantism woven together into a rich tapestry.

By the mid-1770s, Jefferson was ready to join the arguments of other patriots as a writer and statesman in the Second Continental Congress. In 1774, he authored a pamphlet entitled Summary View of the Rights of British America. He wrote that God was the author of natural rights inherent in each human being. The Americans were “a free people claiming their rights, as derived from the laws of nature, and not as the gift of their chief magistrate… the God who gave us life gave us liberty at the same time: the hand of force may destroy, but cannot disjoin them.”

At the Second Continental Congress, Jefferson and John Dickinson wrote the Declaration of the Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms. Congress resolved, “The arms we have been compelled by our enemies to assume, we will, in defiance of every hazard, with unabating firmness and perseverance, employ for the preservation of our liberties; being with one mind resolved to die freemen rather than to live as slaves.”

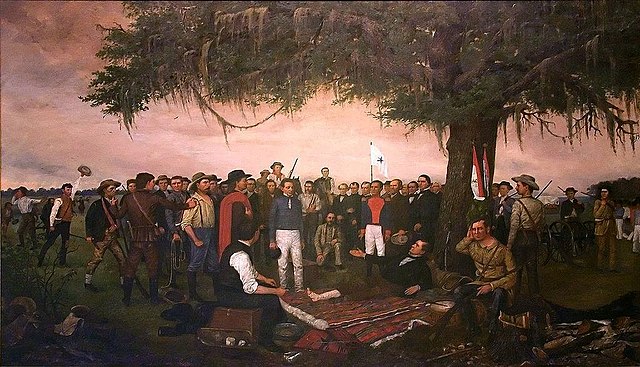

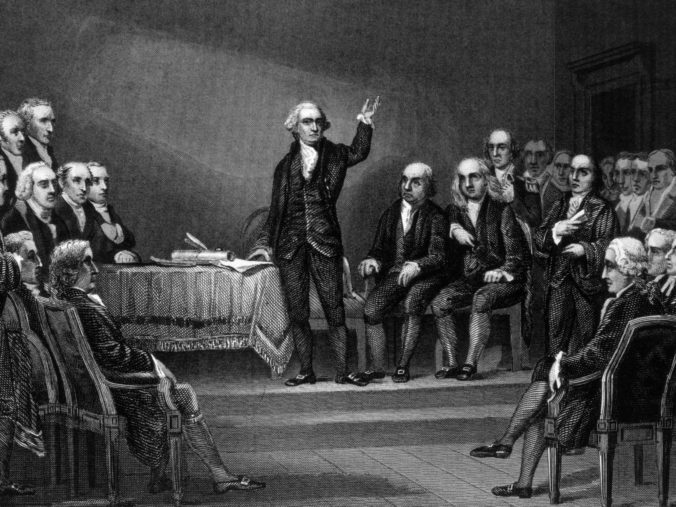

Almost exactly a year later, the Congress declared independence and the ideas liberty and self-government. On June 7, 1776, Virginian Richard Henry Lee rose in Congress and offered a resolution for independence. “That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.” Congress appointed a committee to draft a Declaration of Independence including thirty-three-year-old delegate, Jefferson.

John Adams later explained why he and the committee asked Jefferson to draft the Declaration of Independence. Among the several reasons, Adams stated, “I had a great opinion of the elegance of his pen and none at all of my own.” The elegance of Jefferson’s writing—and of his mind and political thought—was deeply rooted in his classical education.

The committee submitted the document to Congress, where it was considered, edited, and then adopted on July 4, 1776, enunciating the natural rights principles of the American republic. The Declaration claimed that the natural rights of all human beings were self-evident truths that were axiomatic and did not need to be proven. They were equally “endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

The equality of human beings meant that they were equal in giving consent to their representatives in a republic to govern. All authority flowed from the sovereign people equally. The purpose of that government was to protect the rights of the people. “That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” The people had the right to overthrow a government that violated the people’s rights with a long train of abuses.

Thomas Jefferson’s early life and classical education prepared him to author the Declaration of Independence. After this watershed contribution to the creation of the American republic, Jefferson led a life of patriotic public service as a member of Congress, diplomat, Secretary of State, Vice-President, and President during the early republic that witnessed the creation of American institutions, the formulation of domestic and foreign policies, and the expansion of the new nation.

Jefferson died providentially on July 4, 1826 along with his friend, John Adams. It was fitting that Jefferson and Adams died on the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence that they submitted to the Continental Congress, the American people, and the world.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here for next Essay

Click Here for Previous Essay

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Burke#/media/File:EdmundBurke1771.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Burke#/media/File:EdmundBurke1771.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Model_of_Christian_Charity#/media/File:John_Winthrop.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Model_of_Christian_Charity#/media/File:John_Winthrop.jpg Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence. Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Sputnik 1 Replica 1957 NASA

Sputnik 1 Replica 1957 NASA