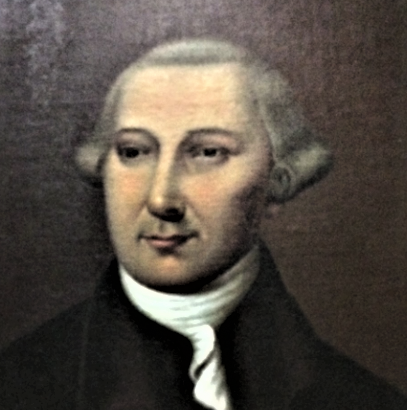

Joseph Hewes of North Carolina: Merchant, State Legislature and Continental Congress Delegate, and Declaration of Independence Signer

History remembers Joseph Hewes as one of the three North Carolina signers of the Declaration of Independence. John Adams, who served in the Continental Congress with Hewes and who would later become president, believed Hewes was critical in persuading moderate members of Congress to support the break with Great Britain.

Raised on his family’s estate near Kingston in what was then West Jersey, Hewes received a classical education in a Quaker grammar school. Rather than obtaining a degree at the nearby College of New Jersey, the forerunner of Princeton University, however, Hewes, in 1749, apprenticed himself to Joseph Ogden, a Philadelphia merchant. Five years later, Hewes declined an offer to join Ogden as a partner, and with money from his father’s estate, went into business for himself. Hewes’s work for Ogden had taken him to North Carolina, and apparently dissatisfied with his Philadelphia enterprise, Hewes moved in 1755 to Edenton, a small but prosperous commercial center on the Carolina coast.

With a likeable, easy-going personality; a natural head for business; and a vigorous work ethic, Hewes quickly rose to the top of Edenton society. He formed a close friendship with Samuel Johnston, one of the colony’s most influential lawyers and political leaders, becoming engaged to Johnston’s younger sister, Isabella, in 1760. She died before they could be wed, but Hewes never married and was treated as a member of the Johnston family for the rest of his life. The year Isabella died, Hewes replaced Johnston as Edenton’s representative to the colonial assembly and served on committees on appropriations and finance, appropriate assignments considering his commercial background.

Hewes eventually became involved in the Whig resistance to British imperial policies, especially the Tea Act of 1773 and the punitive Coercive Acts of 1774, which had been adopted in response to the Boston Tea Party, and he was an original member of North Carolina’s Committee of Correspondence. In June 1774, the committee endorsed a Massachusetts’s proposal for a continental congress, and in August of that year, assembly members meeting in New Bern approved the committee report and elected Hewes, along with William Hooper and Richard Caswell, to represent North Carolina in a meeting in Philadelphia of all the colonies.

While some members of the First Continental Congress seemed ready to resort to force, the North Carolina delegates sided with moderates who held out hope for a peaceful resolution of the crisis. Hewes admired Britain’s constitutional monarchy and feared a violent revolution could lead to virtual mob rule, but he later wrote that he could accept any government the people supported. Despite their differences, the delegates did approve the Continental Association, proclaiming a boycott of British goods as long as Parliament’s objectionable policies remained in place.

Hewes returned to Edenton in late November 1774, suffering from a fever, probably malaria, that would continue to plague him intermittently. He nevertheless remained active, serving on Edenton’s Committee of Safety, which had the responsibility for enforcing the Continental Association in Edenton. The outbreak of fighting at Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts and King George III’s subsequent refusal to negotiate with the colonies undermined the position of moderates like Hewes and led him to act more aggressively. When Congress reconvened in May 1775, Hewes recruited two Presbyterian ministers to rally support for the American cause among Highland Scots in the North Carolina backcountry. Mainly Presbyterians, the Scots had long been estranged from the colony’s politically dominant English Anglican faction to their east. Hewes also served as secretary to Congress’s Naval Board and helped secure John Paul Jones’s commission in the Continental Navy.

In the first half of 1776, Hewes found himself overtaken by events. Parliament’s Prohibitory Act of 1775, outlawing trade with the colonies, had created widespread resentment. In January 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, his fiery call for American independence; Hewes reluctantly forwarded it to North Carolina. In February, the victory of North Carolina militia over a Loyalist force at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge emboldened the colony’s Whigs. In April, the Fourth Provincial Congress, meeting in Halifax, authorized North Carolina’s congressional delegation to support independence. Reserved by nature, preoccupied with his committee assignments, and at the moment the only North Carolina delegate in Philadelphia, Hewes did not introduce the so-called Halifax Resolves in Congress until May 27, when Richard Henry Lee of Virginia presented a similar resolution.

Hewes readily signed the Declaration of Independence and thereafter worked tirelessly for the success of the Revolution, particularly in securing ships and supplies for the American cause, but his conservatism created enemies for him at home. In November 1776, a Fifth Provincial Congress met to draft a constitution for what was now the independent state of North Carolina. The convention split between what historians have traditionally labeled “conservative” and “radical” factions. Conservatives favored a strong executive and property qualifications for voting and holding political office. Radicals wanted to concentrate power in the legislature and to expand the political rights of the less affluent. The result was a compromise that pleased neither side. Hewes had identified with the conservatives, and when the state’s new General Assembly met in April 1777, the radicals, alleging Hewes had enriched himself in his business dealings with Congress and violated the ban in the recently adopted constitution on dual office-holding, defeated his bid for reelection to the Continental Congress.

Hewes might have made a political comeback if not for his failing health. Still popular in Edenton, he was elected to the General Assembly in 1779, and the assembly almost immediately returned him to Congress. An arduous trip to Philadelphia in the summer heat weakened his delicate constitution. By late September he was virtually bed-ridden, and in October he resigned from Congress. Too sick to come home, Hewes died in November at the age of 49 and was buried in the graveyard of Christ’s Church in Philadelphia.

Jeff Broadwater is professor emeritus of history at Barton College in Wilson, North Carolina, where he taught courses on the American Revolution and on the history of the American South. His publications include Jefferson, Madison, and the Making of the Constitution (2019); James Madison, A Son of Virginia and a Founder of of the Nation (2012); and George Mason, Forgotten Founder (2006). He also co-edited, with Troy Kickler, North Carolina’s Revolutionary Founders (2019).

Jeff Broadwater is professor emeritus of history at Barton College in Wilson, North Carolina, where he taught courses on the American Revolution and on the history of the American South. His publications include Jefferson, Madison, and the Making of the Constitution (2019); James Madison, A Son of Virginia and a Founder of of the Nation (2012); and George Mason, Forgotten Founder (2006). He also co-edited, with Troy Kickler, North Carolina’s Revolutionary Founders (2019).

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Bibliography:

Martin, Michael G. “Hewes, Joseph.” In William Powell, ed. Dictionary of North Carolina Biography, 6 vols. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1979-1991, 3: 123-125.

Mitchell, Memory F. North Carolina’s Signers: Brief Sketches of the Men Who Signed the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Raleigh, N.C.: State Department of Archives and History, 1964.

Morgan, Daniel T. and William J. Schmidt. North Carolinians in the Continental Congress. Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair, 1976.

Sikes, E.W. and S.A. Ashe. “Joseph Hewes.” In S.A. Ashe, ed. Biographical History of North Carolina: From Colonial Times to the Present, 8 vols. Greensboro, N.C.: Charles L. Van Nappen, 1906, 3: 172-80.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

This is the best biographical sketch of Hewes on the internet. It’s even better than the one by Michael Martin on the internet. Only Martin’s unpublished M.A. thesis has more details and more information.

There is one small claim that might be considered a mistake. Broadwater refers to the “nearby” College of New Jersey. The college did not move to Princeton until 1756 by which time Hewes was in Edenton. The college was first in Elizabethtown and then Newark, NJ when Hewes was growing up near Princeton prior to 1756. Neither was nearby.

Neither would I call the farm he grew up on an estate. It was a modest farm with a modest stone house that his father Aaron built probably with the help of his older brother who was a stone mason in Pennsylvania. The stone Chester County Court House he built is monument to his skill.