The United States Constitution created many precautions against disunion and faction, but did not provide a failsafe solution; throughout the antebellum period statesmanship, compromise, and institutional development secured union until slavery and secession shattered the union.

As was argued in the last essay, the framers embraced the principle of union and framed a representative system to combat faction and disunion. As the Anti-federalists became increasingly weak after the ratification of the Constitution, Washington’s administration pursued policies to bolster union.

The Constitution created institutions meant to draw the country together and to prevent factions from controlling governmental power as was done under the Articles of Confederation. Publius argued that the Constitution embraced a number of improvements from modern political science to perfect republican government and cement union. The tools from modern political science were enumerated in Federalist 9:

a. The regular distribution of power into distinct departments.

b. the introduction of legislative balances and checks.

c. the institution of courts composed of judges holding their offices during good behavior.

d. the representation of the people in the legislature by deputies of their own election.

e. the ENLARGEMENT of the ORBIT within which such systems are to revolve, either in respect to the dimensions of a single State or to the consolidation of several smaller States into one great Confederacy.

However, Publius argued that there were further Constitutional precautions to retain the “excellencies of republican government” and “lessen or avoid” its imperfections. Throughout The Federalist, Publius explains additional precautions woven into the constitutional structure. He points to “auxiliary precautions” to act as a sort of safety net to ensure that the violence of faction is limited if it penetrates any branch of the federal government. The term “auxiliary precautions” echoes an earlier formulation in James Madison’s essay Vices of our Political System written at the behest of George Washington before the Federal Convention. In that essay, Madison argues that the Articles allowed minority factions to overrun the state governments. The essay made the distinction between the great desideratum[1] (creating a sovereign neutral and powerful enough to stop injustice without becoming tyrannical) and the auxiliary desideratum (getting the noblest characters to be elected, rule, and act according to proper motives). Thus, the most important object of the Constitution is the creation of an impartial and limited federal government to secure rights, and a secondary object is to ensure that the system is administered by virtuous citizens. Although Madison argued that creating a limited impartial government was fundamental, the framers believed that no free government could be maintained without proper administration from good rulers. The auxiliary precautions of the Constitution attempt to mitigate the harm that a faction might inflict if it gains power.

As was argued in the last essay, an important aspect of securing an impartial government is distributing and maintaining the partitions of power, which requires that weak branches be fortified and strong branches be weakened. When Publius considers the branch that most needs fortified against, he settles upon the legislative because it was often the legislatures that dominated the state governments under the Articles. In Federalist 48, he arrives at the conclusion that “in a representative republic, where the executive magistracy is carefully limited both in the extent and duration of its power; and where the legislative power is exercised by an assembly, which is inspired by a supposed influence over the people with an intrepid confidence in its own strength; which is sufficiently numerous to feel all the passions which actuate a multitude; yet not so numerous as to be incapable of pursuing the objects of its passions, by means which reason prescribes; it is against the enterprising ambition of this department, that the people ought to indulge all their jealousy and exhaust all their precautions.” Notice the similarity between Publius’ description of a legislature in Federalist 48 and a faction in Federalist 10. A legislature has a “supposed influence over the people,” it is a joint assembly which gives it the convenience of “concert,” it is numerous and can become impassioned through proceedings, yet it is small enough to make plans to “approach its passion.” In other words, the legislature gives a faction the power to exact its designs if it can properly organize itself. Publius therefore sought to limit it with auxiliary precautions such as a bicameral house with short terms, staggered elections, and two relatively large bodies. Note that Publius’ assessment is almost the opposite of Alexis de Tocqueville’s, who fears a soft despot seizing executive power and capitalizing from the lack of civic virtue among the people.

Despite Publius’ fears about the legislature, throughout Washington’s first term it became clear that the legislature was too weak to organize itself and pursue an agenda; instead of driving legislation, it looked to the president. For instance, in 1791 Congress called upon Secretary of Treasury Alexander Hamilton to help frame economic legislation. The House spent several days debating the propriety of considering Hamilton’s economic plans but did not bother drafting or proposing any of its own. The numerous House of Representatives was so unorganized and heterogeneous that it was not capable of creating any bills to put on the floor for a vote. Perhaps Publius underestimated the natural strength of the legislature in large republics. Did he not understand the distinction between this federal legislature set over a large sphere and encompassing a variety of interests and the state legislatures encompassing small territories with homogenous interests under the Articles?

By Thomas Jefferson’s presidency the congress was no less dysfunctional. It was consensus that Congress was weak and it looked to the presidency or the cabinet to drive federal policy. How different was this arrangement from the oligarchies in the state legislatures Madison criticized under the Articles? How much safer were minority rights from factions under this Constitution where the executive wielded such power?

Why was the Congress so weak? President Jefferson noted that representatives “are not yet sufficiently aware of the necessity of accommodation and mutual sacrifice of opinion for conducting a numerous assembly.” An anecdote puts Jefferson’s criticism a bit more sharply: after Jefferson’s message in December of 1805 was referred to the committee of the whole, it took almost a full session to determine a single resolution. After the message was referred to the Committee of the Whole, a section on harbor defense was approved and turned to committee. The Committee on Defense determined measures, and then on January 23 the report was taken up by the Committee of the Whole. The Committee on Defense decided on a sum for harbor defense, the Committee of the Whole disagreed, then appointed a committee of two to call upon the president for more information. In February the discussion was resumed. The House passed two resolutions: one sum for harbors and one sum for gunboats. A committee was then appointed to draft a bill in accord with these resolutions. On April 15, the committee began its debate on the bill to appropriate the money for harbor defense. The process in 1805 led four different committees to discuss two resolutions for defense over the course of five months: and that was just one plank of a bill, considering one part of the president’s annual message, in just the House of Representatives! James Sterling Young notes that the biggest problem was that “Any legislator had the privilege of bringing forward, at any moment, such measures as suit his fancy; and any other legislator could postpone action on them indefinitely by the simple expedient of talking.”

In addition to institutional problems, the representatives lacked the revolutionary unity common at the time of the Founding. One representative noted, “The more I know of [two senators] the more I am impressed with the idea how unsuited they are ever to co-operate, never were two substances more completely adapted to make each other explode.” On one hand a New England representative claimed of his Southern colleagues that they were “accustomed to speak in the tone of masters” and that the Westerners had “a license of tongue incident to a wild and uncultivated state of society. With men of such states of mind and temperament, men educated in New England could have little pleasure in intercourse, less in controversy, and of course no sympathy.” A Southern representative remarked of his New England colleagues that “not one possesses the slightest tie of common interest or of common feeling with us.” In addition to feelings of discord, there were physical altercations brought about by the pains of living in common boarding houses. An incident is recorded in Miss Shields’ house when John Randolph, “pouring out a glass of wine, dashed it in [Rep. Willis] Alston’s face. Alston sent a decanter at his head in return, and these and similar missiles continued to fly to and fro, until there was much destruction of glassware.”

How were we to call ourselves a republic if the representative branch could not govern themselves at their own tables, let alone within the chambers of Congress? In Publius’ lifetime as in our own, Congress needed to develop institutional tools to overcome its weakness and become a functional branch of government. This was necessary if the ambition of the legislature was to become sufficient to check the ambition of the executive branch and preserve our republican form of government.

Throughout the Antebellum Period, Congress developed institutional tools which allowed it to enact legislation without relying solely on the executive branch for direction. The most important institutional changes from the American Revolution through the Antebellum Period were rules, committees, coalitions, compromise, and statesmanship through oratory. Although I will not have the length to discuss each development in depth, I will cover some of the most important developments in Congress throughout the Antebellum period.

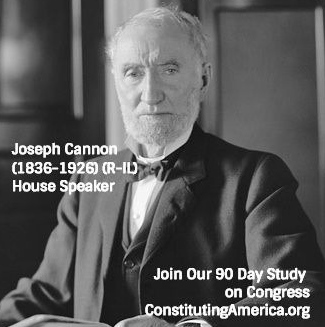

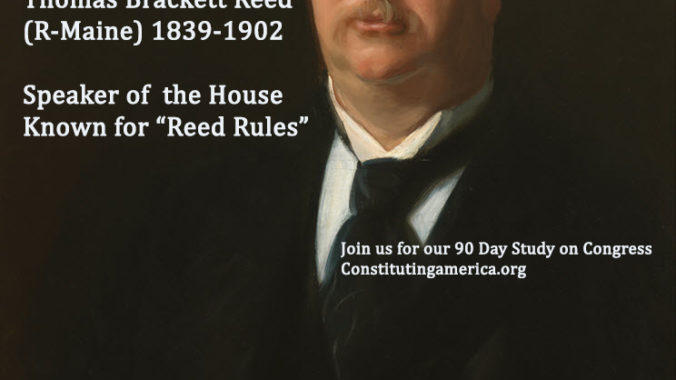

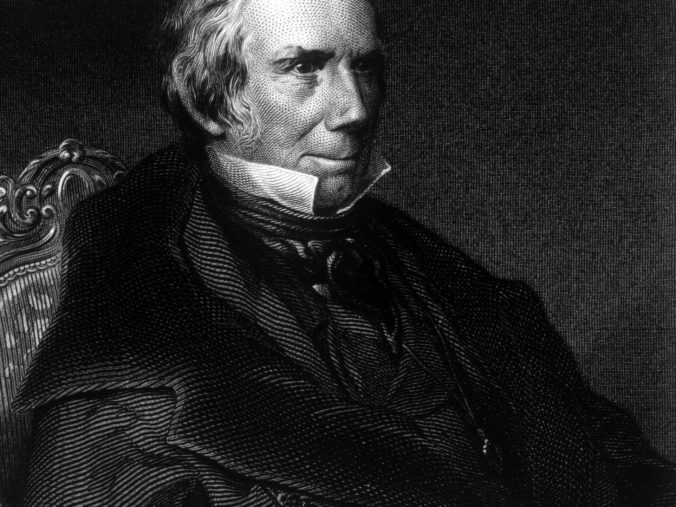

Henry Clay was the most seminal figure in developing the institutional reforms which allowed Congress to assume the role of legislative leader. On November 4, 1811, Clay was elected Speaker of the House on his first day as a member and on the first ballot. He won seventy-five votes, while William Bibb won thirty-eight, and Nathaniel Macon won three. Mary Parker Follett remarks that “Clay was elected more than any other Speaker as leader of the House. Never before and only once since has a member been distinguished with the honor of an election to the chair upon his first appearance in the House.” The caucus that met before electing Clay Speaker was clear about its intentions. One of Clay’s partisans asserted that the House was in need of a Speaker who would “bridle” John Randolph. Another member said that “he (Randolph) disregards all rules.” Another man asserted that the Speaker “must be a man who can meet John Randolph on the floor or on the field, for he may have to do both.” Clay would eventually do both. One of Randolph’s favorite tactics was to bring his hunting dogs to the chamber where he would use them to intimidate other members and cause disruptions when proceedings were not to his liking. One of Clay’s very first acts as Speaker was to institute a rule barring animals from the chamber during business. In 1826 the two men dueled after Randolph insulted Clay, but both missed their marks, and unhurt met each other halfway to shake hands (something that the two could never manage to do politically).

Clay’s early rules were a sign of his prerogative as legislative leader: he believed that the majority in Congress, elected by a majority of the people, should be equipped with the tools to govern. This principle animated him throughout his congressional career, but also required that he attain more power as Speaker to silence the minority. Mary Parker Follett claims that Clay’s leadership aimed at producing order. She writes, “The new principles set forth during Clay’s long service were: first, the increase of the Speaker’s parliamentary power; secondly, the strengthening of his personal influence; and thirdly, the establishment of his position as a legislative leader.” Clay drew criticism as he increased his power but it was also clear that he was capable of passing policies that advanced the country into the boom of the industrial revolution.

The most radical change in the House of Representatives during the antebellum period was a change that still characterizes it today: the creation of standing committees to expedite business and develop policy expertise. Between the War of 1812 and the Civil War, the House increasingly relied on standing committees to debate and amend measures. As this reliance on standing committees steadily expanded, the House’s relationship with standing committees changed: measures were first referred to committee for consideration and only after being reported by committee were they debated by the full House. This expedited the law-making process because the Committee of the Whole allowed any member to debate on any bill and delay the majority; a liberty that the minority would slowly lose through the Clay Speakership. But how much did the committee structure grow during the Antebellum period? At the time of the Founding the House of Representatives had only one standing committee and relied on ad-hoc committees. By 1810 the House had 10 standing Committees. In 1816 the Senate established 12 permanent committees. By the Civil War the House had 39 standing committees and the Senate had 22.

The new developments in Congress ensured that independents like John Randolph would play an increasingly smaller role in policy-making and that coalitions would play an increasingly greater role. Henry Clay believed in a system animated by coalitions because he believed that such a system provided the opportunity for compromise and energy within the legislature. According to Clay, a coalition-led process of deliberation and choice, as opposed to a member-centered process, meant that creating consensus and collapsing distinctions about factious issues would be more common, and policies of pressing concern would be passed expeditiously. However, in organizing the Congress Henry Clay empowered it to act more efficiently. Did this new energetic Congress exceed the limitations Publius intended for the Federal Government?

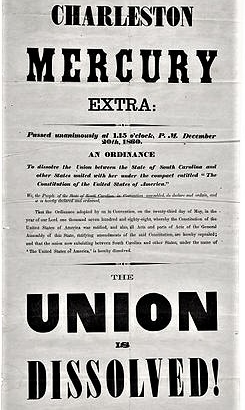

In the early 1830s John Calhoun argued that the policies enacted by the energetic Congress harmed the interests of the minority; further, he argued that the people of a state should be able to nullify a federal law if its people deemed it oppressive. He argued that the energetic Congress, passing tariffs that harmed southerners and using federal funds for roads that empowered manufacturers at the expense of farmers, had wielded unchecked power to favor Northern interests. He wrote, “The Government of the absolute majority instead of the Government of the people is but the Government of the strongest interests; and when not efficiently checked, it is the most tyrannical and oppressive that can be devised.” He argued that the state of South Carolina should be able to nullify and ignore the Federal Tariff laws on imports. However, South Carolina never nullified the federal tariff; Andrew Jackson threatened to use the army to collect tariffs and congress passed a Force Bill allowing him to do so, and Henry Clay passed a Compromise Tariff which would reduce the tariff over time to appease the state of South Carolina.

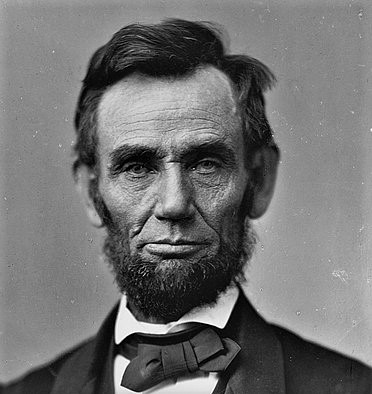

The Southerners deemed tariff laws oppressive, but nothing stoked the flames of disunion more than Congressional action upon slavery in the territories. Although South Carolina never effectively nullified the federal tariff, over the next thirty years the Southern states developed a constitutional theory of secession to combat the power of Congress which they deemed oppressive of their property rights and economic interests. In 1850, Jefferson Davis declared in the Senate, “every breeze will bring to the marauding destroyers of southern rights the warning ‘Woe, woe to the riders who trample them down!’” He argued that Congress had used its power to the detriment of Southern interests, and that they deserved extra protection for slavery or they may secede from the union. Of slavery, he argued, “This is the most delicate species of property that is held: it is the property that is ambulative; property which must be held under special laws and police regulations to render it useful and profitable to the owner.” When Abraham Lincoln was elected, Jefferson Davis argued that Lincoln’s hostility toward the expansion of slavery allowed the Southern states to secede from the union. He argued “Secession belongs to a different class of remedies. It is to be justified upon the basis that the States are Sovereign. There was a time when none denied it.”

As Dr. Eric Sands articulated for this study, in his essay on the Civil War and consequences of secession, Lincoln argued that secession was unconstitutional and threatened the principle of self-government. He argued that there could be no form of republican government if the losers of an election were free to secede in order to avoid the consequences of unpopular political beliefs. He said that the union was Perpetual; he argued that the Constitution intended that the union endure forever, and that the doctrine of secession was contrary to the most fundamental premise of the Constitution.

However, Davis and others argued that over the course of the Antebellum Period, the federal government had expanded its Constitutional power and used those powers oppressively toward the interests of the slave states. Lincoln argued that Davis was wrong; States were not sovereigns under the Constitution, and the common interests of union superseded their individual interest in the expansion of slavery and the protection of slaves as property.

Despite the philosophic differences, it is clear that as Congress lost the ability to collapse differences through virtue and statesmanship, and promote union through compromise, the union was destined to dissolve. The framers admitted that this was the case; that representative self-government relied upon a functional representative branch of government that protected and advanced the interests of citizens. Is our Congress capable of compromise, statesmanship, and advancing our common interests today? Perhaps the tools that quelled disunion throughout the Antebellum period could help solve our congressional crisis today.

Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of The Center for Liberty and Learning at the Founders Classical Academy of Lewisville, Texas. Mr. Postell graduated from Ashland University with undergraduate degrees in Politics and English. He earned his master’s degree in Political Thought from the University of Dallas and is working on his dissertation to complete his Ph.D. Mr. Postell is writing a book on Henry Clay and legislative statesmanship, a subject about which he frequently writes and publishes. He has also conducted studies for Ballotpedia and has frequently contributed to Law and Liberty and Constituting America. At Founders Classical Academy he teaches courses on Government and Economics, and has taught courses on American Literature and Rhetoric.

Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of The Center for Liberty and Learning at the Founders Classical Academy of Lewisville, Texas. Mr. Postell graduated from Ashland University with undergraduate degrees in Politics and English. He earned his master’s degree in Political Thought from the University of Dallas and is working on his dissertation to complete his Ph.D. Mr. Postell is writing a book on Henry Clay and legislative statesmanship, a subject about which he frequently writes and publishes. He has also conducted studies for Ballotpedia and has frequently contributed to Law and Liberty and Constituting America. At Founders Classical Academy he teaches courses on Government and Economics, and has taught courses on American Literature and Rhetoric.

[1] Desideratum is Latin, meaning “thing desired.”

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Charleston_Mercury_Secession_Broadside,_1860.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Charleston_Mercury_Secession_Broadside,_1860.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Lincoln#/media/File:Abraham_Lincoln_O-77_matte_collodion_print.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Lincoln#/media/File:Abraham_Lincoln_O-77_matte_collodion_print.jpg