He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only.

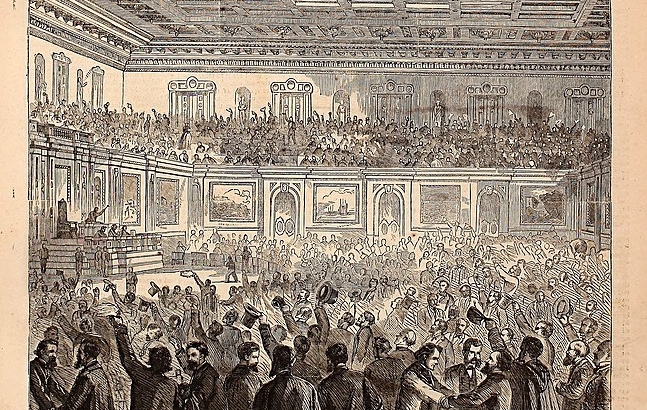

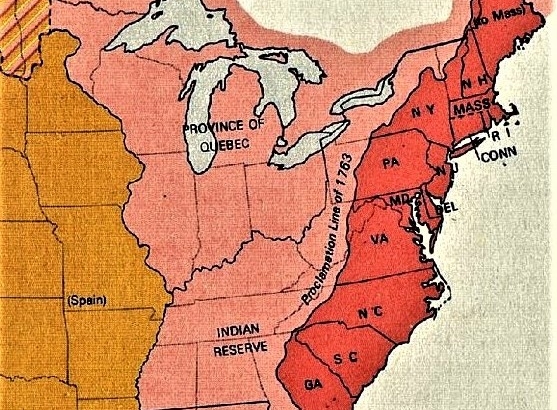

With the population growth in the colonies, the local assemblies and legislative bodies grew in numbers and power. In New Hampshire, New York, South Carolina and Virginia, King George restricted the size of assemblies thereby denying new communities representation in the colonial assemblies. The colonists took it as their right to have their interests represented in a legislative body. Denying this denies their right to govern.

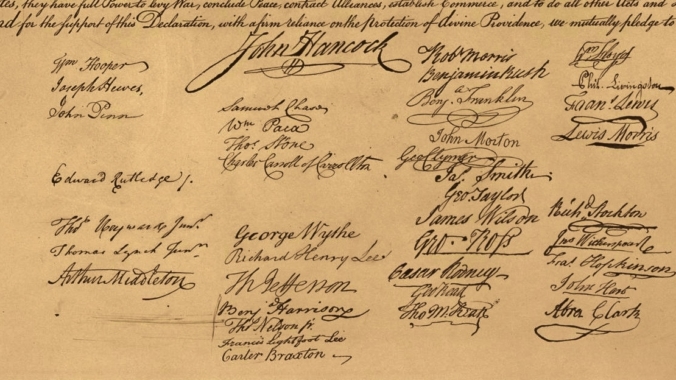

The colonists had been allowed to decide how they would be represented in localities. By voiding this practice, there was a breach of trust that threatened the colonists’ ability to pursue the public good as they understood it. John Locke wrote, “Governments are dissolved…when the legislative, or the prince, either of them, act contrary to their trust.” In this formulation, King George effectively dissolved the government by breaching the trust of the colonists. However, while this is a valid position, it is thin justification as it would give far too much leeway to those looking to dissolve the bonds between themselves and government.

Thomas Jefferson makes clear in the Preamble that a single violation of trust is not enough to justify a move to independence. To create a thicker justification, we must look at a tangentially related issue. Within the act of denying representation is lack of adherence to the rule of law as defined by long accepted practices in accordance with the public good. Instead of adhering to the practices of expanding representation in the assemblies when population growth dictated it prudent, King George replaced common practice with his will to control. Furthermore, rather than following standard practices—such as going through parliament or the colonial governments—to change the law, he acted with singular caprice.

By expanding their assemblies to accommodate population growth, the colonies were following the procedures and processes that had been in place up to that point. King George’s actions did not follow precedent and had no recourse to the common good or legal principle, but represented his will to control. This capricious decision based on nothing more than his will to exert power is a violation of the fundamental principle of what gives government legitimacy. When the King works for his good only it is a dereliction of duty and gives those governed the right to dissolve the bonds of government.

King George has acted not in the best interests of those he governed, which is what grants him authority to rule, but has acted in his own best interests in contradistinction to the good of the colonists. This is a consistent theme which ties all twenty-seven grievances together, and which receive their philosophical justification in the Preamble. Embedded within this grievance is an assumption of coequal branches of government with divided powers which substantiates the claim that the Declaration of Independence can be viewed as a governing document—one that bridges the common law and the codified constitution traditions. An executive—in this case a King—does not have the right to alter the legislature without a law being passed by that legislature which assumes a level of equality and divided power between two branches. It’s a tacit overthrow of monarchical rule and a presumption of equality that will define James Madison’s later project.

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA serves on the Board of Trustees for the Lone Star College System and teaches political science at the University of Houston and is an affiliated scholar with the Baylor College of Medicine’s Center for Health Policy and Medical Ethics. Kyle has authored over 70 op-eds, dozens of academic articles and five books, the most recent of which is The Limits of Politics: Making the Case for Literature in Political Analysis. He can be reached at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com or on Twitter: @kanthonyscott.

Click Here for Next Essay

Click Here for Previous Essay

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

NationalAtlas.gov

NationalAtlas.gov

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA serves on the Board of Trustees for the Lone Star College System and teaches political science at the University of Houston and is an affiliated scholar with the Baylor College of Medicine’s Center for Health Policy and Medical Ethics. Kyle has authored over 70 op-eds, dozens of academic articles and five books, the most recent of which is The Limits of Politics: Making the Case for Literature in Political Analysis. He can be reached at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com or on Twitter: @kanthonyscott.

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA serves on the Board of Trustees for the Lone Star College System and teaches political science at the University of Houston and is an affiliated scholar with the Baylor College of Medicine’s Center for Health Policy and Medical Ethics. Kyle has authored over 70 op-eds, dozens of academic articles and five books, the most recent of which is The Limits of Politics: Making the Case for Literature in Political Analysis. He can be reached at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com or on Twitter: @kanthonyscott.