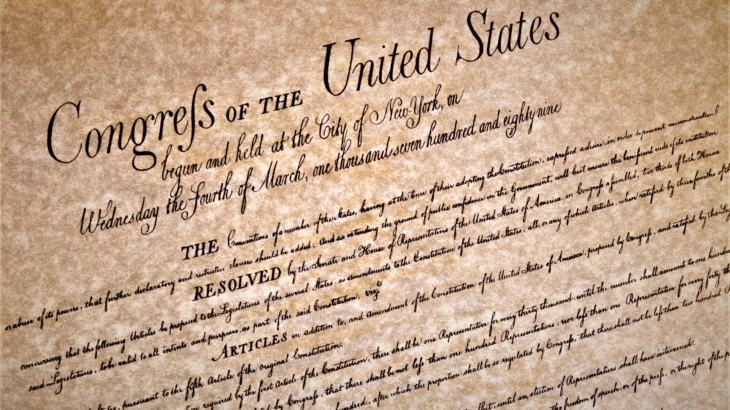

Ratifying a Bill of Rights to the United States Constitution and the Safeguarding of America’s Freedoms

In 1789, James Madison spoke on the House Floor introducing amendments to the U.S. Constitution, an attempt to persuade Congress a Bill of Rights would protect liberty and produce unity in the new government. Opposed to a Bill of Rights at first, Madison stated that the rights of mankind were built into the fabric of human nature by God, and government had no powers to alienate an individual’s rights. Having witnessed the states violating them, Madison realized in order to safeguard America’s freedoms, Congress needed to remain mindful of their role never to take a position of power by force over the people they serve.

There was probably no American more interested in what was taking place in Richmond, Virginia that brisk December morning in 1791 than James Madison. Christmas had come and gone and now Congress entered the last week of the year. The second-term U.S. Congressman from Virginia’s 5th Congressional District could only sit patiently in Mrs. House’s boarding establishment in Philadelphia and wait for a dispatch-rider carrying news from his home state. It must have been frustrating.

In the waning days of 1789, the Virginia Senate had outright rejected four of the proposed amendments, an ominous sign. The ratification by ten states was necessary (the admission of Vermont in March, 1791 bumped that up to eleven) and Virginia’s rejection did not bode well for Madison’s “summer project.”

Madison had single-handedly pushed the proposed amendments through a reluctant Congress during the summer of 1789, a Congress understandably focused on building a government from scratch. But push them through he did; a promise had to be kept.

Madison’s successful election to the First Congress under the new Constitution (by a mere 336 votes) had been largely due to a promise the future fourth President made to the Baptists of his native Orange County. “Vote for me and I’ll work to ensure your religious liberty is secured, not just here in Virginia but throughout the United States.” And vote for him they had.

Upon taking his seat in the First U.S. Congress, then meeting in New York,[1] “Jemmy” had encountered the ratification messages of the eleven states which had joined the new union. North Carolina and Rhode island would as well, eventually. Several of these ratification messages contained lengthy lists of proposed amendments which became Madison’s starting point. He whittled down the list, discarding duplicates and those with absolutely no chance for success, and submitted nineteen proposed amendments to Congress. These were “wordsmithed,” combined, some good ones inexplicitly discarded, and the lot reduced further to twelve, which were finally approved and submitted to the states for ratification on September 28, 1789.

Three states: New Jersey, Maryland and North Carolina quickly ratified almost all of the amendments before the end of the year. [2] South Carolina, New Hampshire, Delaware, New York, Pennsylvania and Rhode Island ratified different combinations of amendments in the first six months of 1790. And then things came grinding to a halt. The remaining four states would take no further action for more than a year.

Massachusetts, Connecticut and Georgia were dragging their feet. The three states did not fully ratify what we know today as the Bill of Rights until its sesquicentennial in 1939! The new state of Vermont ratified all twelve articles in early November, 1791, but Congress would not learn of that for two months. Who would provide the ratification by “three-fourths of the said Legislatures” needed to place the proposed amendments into effect?

Here at the end of 1791, things were finally looking promising. On November 14th President George Washington informed Congress that the Virginia House of Delegates had ratified the first article on October 25th, agreed to by the Senate on November 3rd. But what about the remaining eleven articles? Was that it? Although now ratified by Virginia, this first Article still lacked ratification by 11 states, so Virginia’s action had no real effect.

Unbeknownst to Madison and the rest of Congress, on December 5th, the Virginia House of Delegates had ratified “the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth, tenth, eleventh, and twelfth articles of the amendments proposed by Congress to the Constitution of the United States.” Ten days later, the Virginia Senate concurred. It would be another seven days before Assembly President Henry Lee sent off the official notice of his state’s ratification to Philadelphia and several more days before it arrived. On December 30th, President Washington informed Congress of Virginia’s action.

But wait. Vermont’s ratification had still not made its way from that northernmost state. Congress pressed on with other urgent matters. Finally, on January 18, 1792, Vermont’s ratification finally arrived. With it, Congress realized that Virginia’s December ratification had indeed placed ten of the Amendments into operation.

The rest of America symbolically shrugged its shoulders and went about its affairs. In the words of historian Gordon S. Wood, “After ratification, most Americans promptly forgot about the first ten amendments to the Constitution.”[3] It would be nearly 70 years before Americans even began referring to these first ten amendments as a “Bill of Rights.” Today, we seek their protections frequently, and vociferously. Bravo, Mr. Madison!

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] Congress moved from New York to Philadelphia between August and December of 1790.

[2] New Jersey declined to ratify Article Two, until 1992.

[3] Quoted in James Madison and the struggle for the Bill of Rights. by Labunski, Richard E., Oxford University Press, 2006, p. 258.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!