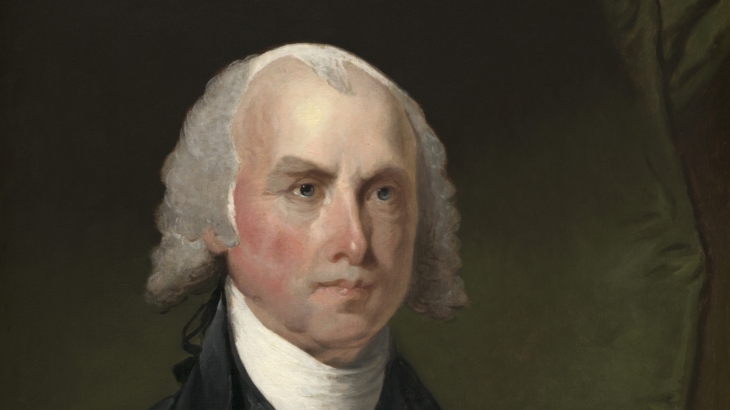

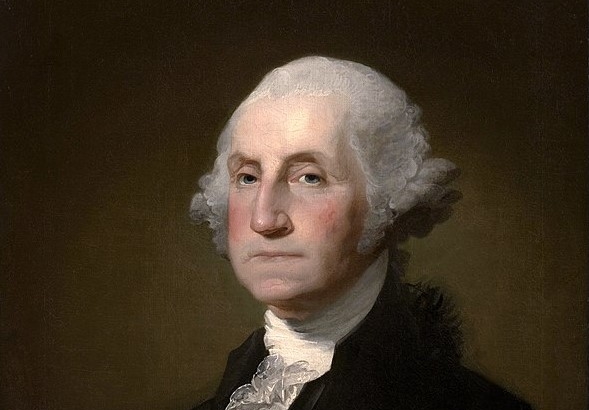

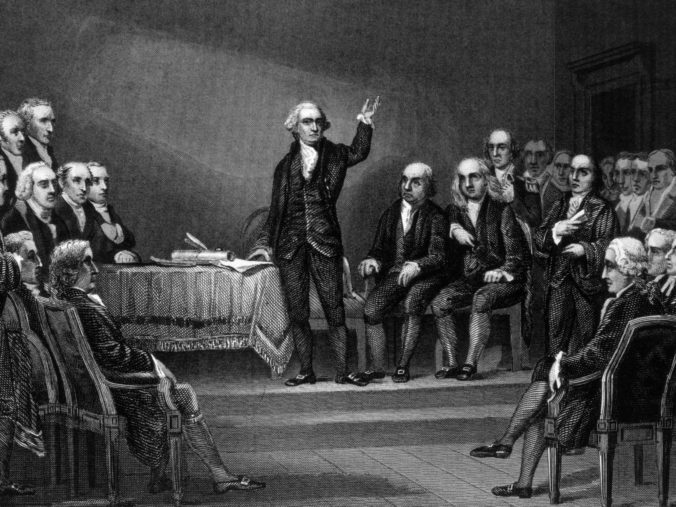

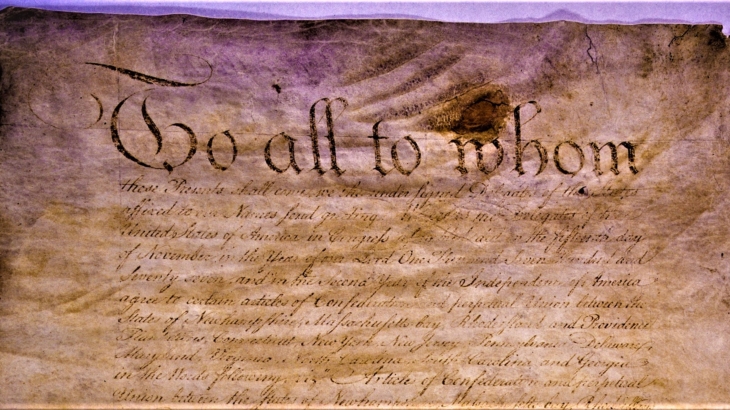

The United States Constitution is the product of a process which attempted to address perceived inadequacies of the Articles of Confederation in dealing with practical problems of governance. Its writers sought to provide practical solutions, shaped by their experiences. On that matter, it was irrelevant whether the Philadelphia Convention technically acted outside its charge from the states and the Confederation Congress and produced a revolutionary new charter, which argument James Madison disputed in The Federalist, No. 40, or whether the Constitution was a mere extension of the Articles and “consist[ed] much less in the addition of NEW POWERS to the union, than in the invigoration of its ORIGINAL POWERS,” as he averred in essay No. 45.

There are numerous devices in the Constitution to frustrate utopian schemes. Most of them are structural. The drafters understood that utopian schemes were more likely to succeed in smaller and more homogeneous communities. Madison in The Federalist, No. 10, identified the problem as one of faction, where members of a community joined by a common passion to gain power. Derived from the natural inequalities among human beings, factions are a foreseeable part of society. While democracies are most susceptible to control by an entrenched faction, small republics are not immune. The danger somewhat abates across a state but is least likely to occur in the nation and within its general government. As he explained. Vividly:

The influence of factious leaders may kindle a flame within their particular states, but will be unable to spread a general conflagration through the other states: a religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national councils against any danger from that source: a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district, than an entire state.

Madison continued along the same vein in essay No. 51, “In the extended republic of the United States, and among the great variety of interests, parties, and sects, which it embraces, a coalition of the majority of the whole society could seldom take place upon any other principles, than those of justice and the general good …. And happily for the republican cause, the practicable sphere may be carried to a very great extent, by a judicious modification and mixture of the federal principle.” [Emphasis in the original.]

In Madison’s view, emergence of a permanent majority faction was more concerning, as minority factions would be controlled through majority voting. Fortunately, the diversity of religious, economic, ethnic, and customary influences creates shifting alliances among various factions, none of which would become an established majority at the national level. This creates a protective moat for society against dangers from radical policies which one faction might seek to impose on the country. In addition, the structural balance of formal constitutional powers between the national government and the states, further prevents any utopian faction in one state from readily spreading to another. This “federal” structure is enhanced by what Madison considered to be the adoption within the Constitution of the principle of subsidiarity, that is, that most political matters would be handled at the lowest level of political units, rather than by Congress.

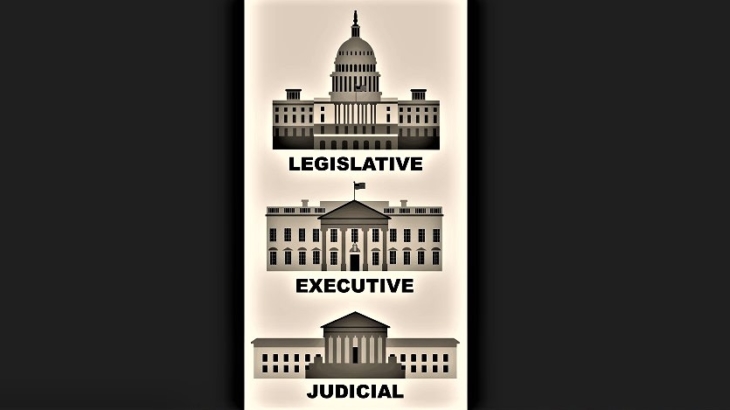

In essay No. 51, Madison also explained another protection against a radical utopian faction gaining hold of the national government, the separation of powers. That separation consists of two parts in the Constitution, namely, provisions which guarantee to each of the branches a degree of immunity and independence from the other, as well as provisions which create a blending and overlapping of functions and require the different branches to collaborate to create policy. Examples of the first group of provisions are the control each branch of Congress has over its membership and the immunity of its members from prosecution for debates in Congress; the President’s privilege to withhold information from the other branches protected under, among other sources, the “executive power” clause; and the Supreme Court’s tenure during “good Behavior.” Examples of the second are the Congress’s power of the purse, the requirement that both chambers agree to the same legislation, the President’s qualified veto over legislation, and the Court’s power of judicial review. These protections help guard against rash policies and, as Alexander Hamilton phrased it in The Federalist, No. 78, “dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community.” Moreover, many state constitutions incorporate similar principles of separate, yet overlapping, powers.

Leaving aside the unelected judiciary, the selection process for these positions supports the protection against radical utopian factions. Much of the operation of the political system under the Constitution, as distinct from its substantive powers, is ultimately founded in the federal system of states. Madison addressed the complex interrelationship between national and federal characteristics of the Constitution in The Federalist, No. 39. The people elect the House of Representatives, and representation is apportioned among the states on the basis of population, which are “national” characteristics. However, the states respectively determine the qualifications of the voters through their control over the electoral franchise for their own legislatures. Moreover, each state is guaranteed at least one seat, so even the population basis of the House is qualified by the existence of the states. The Senate is organized on the basis of the equality of the states in their corporate political capacities, a “federal” characteristic, and members originally were elected by the state legislatures. The president is selected by a body which is based on allocations of electoral votes among the states through a combination of population and state equality. Moreover, these electors are selected by the state legislators. As Madison explained in essay No. 39, the eventual election of the president was expected to be made by the House of Representatives, but on that occasion voting by state delegations.

The state-centric nature of these operative aspects of the constitutional structure helps diffuse power among various constituencies within a state and among different states. House members today are typically elected in single-member districts, whose constituents might be quite diverse from district to district. As originally envisioned, presidential candidates were selected by electors through a national, or at least regional, frame of reference. With the advent of modern political parties and the demographic changes over the past century, the president today is elected by a national constituency. Still, having to gain the endorsement of one of the two major political parties by having to appeal to different types of constituencies complicates the efforts of a radical faction’s candidate to gain sufficient power to orient the nation’s policies in a utopian direction. Political pragmatism and compromise is the inertia within the system.

One might add to these constitutional rules others of a more institutional origin. One such device which protects against utopian projects by a majority faction is the Senate’s “filibuster” rule. Another is the collection of arcane parliamentary procedures in the houses of Congress which can be used to derail or moderate legislation. Yet another is the committee structure and, at least in the past, the seniority system for chairmanships when powerful committee chairmen could frustrate the demands of the majority.

The problem with this presentation of a system of machine-like operation under clear constitutional rules that create a carefully-calibrated balance among various political actors, all while allowing government to function, yet protecting minority rights and guarding against dangerous utopian tendencies, is that it flatters irrationally. Seeing the political system only through the technical functioning of the rules is slanted and presents what one might call a “utopian” view. In fact, a hard look at the current system is needed to see how differently it operates.

At the level of national versus state governments, both consume a vastly greater percentage of Gross Domestic Product than a century ago, never mind two centuries ago. The national government’s share in particular has increased manifold. The national debt is at a record peacetime high in relation to GDP. The current use of debt by all levels of government would make the schemers in the state governments of the 1780s blanch. Congress today uses its legislative powers over interstate commerce, taxing, and spending to intrude into the most local and personal activities. Madison’s explanation in essay No. 39 of The Federalist that the national government’s jurisdiction extends to only a few enumerated ends, while the states have “a residual and inviolable sovereignty over all other objects” seems quaint and quizzical. Indeed, the very concept of residual state sovereignty has been neutered through Congress’s use of its taxing and spending powers, just as the Anti-federalists predicted and Hamilton attempted to refute in essays No. 32 and 33 of The Federalist. Prodigious government grants of money are a lifeline for much academic research, and those funds are readily applied to advance utopian projects by their recipients. As to legislation at the state and local levels, the ubiquity of laws far surpasses that of the earlier time, a product perhaps of a more complex society or the fact that legislating has become a full-time occupation for many politicians today.

As to the separation of powers, the contrast between the Constitution’s text and the operation of the system is if anything, starker. The proliferation of “alphabet agencies,” unencumbered by doctrines of separated functions, make rules, enforce them, and adjudicate violations of those rules in formally civil, but functionally criminal, proceedings. Those rules, adopted by generally unaccountable “independent” commissioners, administered by career functionaries, and virtually immune from judicial challenge, constitute the vast majority of the American corpus juris. There has been significant research into the political tactic of “regulatory capture,” whereby private entities, be they businesses, unions, or ideological “NGOs” (Non-Governmental Organizations) effectively take control of regulatory agencies. The danger with the last of these is that they often pursue utopian agendas behind the label “public interest,” rather than the more prosaic economic benefits to which the first two usually direct themselves.

There has been a concomitant expansion of executive power. The growth of the White House budget for various in-house offices, agencies, and directors which often parallel the domains of the formal constitutional departments, yet are independent of them, is one measure. As well, vast delegations of authority by Congress to the executive branch occurred as early as the Woodrow Wilson administration. The Supreme Court took some desultory steps against such delegations during the 1930s. Justice Felix Frankfurter warned about the expansion of executive power in his concurrence in Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer, the famous Steel Seizure Case in 1952. Yet the Supreme Court has not struck down such a delegation in nearly a century. Some of this delegation, as well as broad ritualistic claims of inherent executive authority, arose in connection with war or other emergencies. Unsurprisingly, those powers continued during peace. A claim of discretionary power to act in emergencies inevitably produces more claims of emergencies. As shown by quite recent history, similar displays of broad executive power and uncontrolled administrative governance are part and parcel of state and local systems, as well.

As to constitutional barriers to utopianism provided by the electoral structure, or institutional barriers through the filibuster, one must wonder about their continued efficacy. Gerrymandering of districts has produced many “safe” partisan districts, where primary elections control the eventual outcome. Primary elections—or local party caucuses—attract the most ideologically committed participants. Such gerrymandering has been blamed for the election of candidates committed to ideologically pure, but practically harmful, utopian policies.

The mobility of American society and the advances in communications technology and entertainment have challenged Madison’s basic assumption about the diversity of interest groups rooted in different geographical areas. The electorate has become much more homogeneous and “national,” so that a nation-wide electoral majority might degenerate into an ideological faction similar to what Madison described was the danger in a local democracy. Candidates, too, are less dependent on the moderating influences of party organization. One need only to consider the emergence of billionaire-politicians and celebrity-politicians who can use their money or status to capture a party’s nomination and, subsequently, the office, without the support of the party’s established apparatus. Institutional restraints, such as the filibuster, have been weakened and are threatened with elimination, which would further undermine protections against a bare majority faction in Congress imposing utopian projects on the country.

Madison dismissed the dangers of a minority faction controlling Congress because of the “republican principle” of majority vote. But a minority faction driven by utopian fervor is much more likely to coalesce than a majority, and Madison’s faith in the vote is too blind to that danger. It has long been established that an ideologically committed organized minority can control an unorganized majority in politics or otherwise. The large economic or psychological benefits of a policy to the members of the minority outweigh the proportionally smaller costs to each member of the majority. With the increased and hidden power of unelected entities described earlier, the danger becomes more acute. One example should suffice: Before his inauguration, President-elect Donald Trump challenged leaked, unsubstantiated claims by American intelligence agencies that Russia had hacked the 2016 election. Senator Charles Schumer then warned President Trump, “You take on the intelligence community—they have six ways from Sunday at getting back at you.” Schumer was not alone in that prognosis. The specter of the hidden intelligence apparatus undermining the president in pursuit of an ideological objective has been raised many times over the past decades and is in direct conflict with the constitutional order.

In similar manner, the doctrine of judicial review has increasingly been used to advance constitutional novelties. The Constitution provides a formal amendment process, based on broad super-majoritarian approval that is, in Madison’s description, partly federal and partly national. It requires broad consensus in Congress and among the people or legislatures of the states. There has also developed an informal amendment process which retains elements of popular approval and consensus. For example, when Congress passes a law, the president signs it, and there is no successful constitutional challenge brought to the law in the courts, continued and open adherence to that law by the people over time makes that law’s political essence part of the constitutional fabric. A similar development occurs if a significant number of states pass laws respecting a particular matter of state control, if those laws do not conflict with a clear constitutional provision. A constitutional challenge to such well-established laws years later ordinarily should be rejected, because, as Hamilton stated, the purpose of judicial review is to prevent sudden popular passions from passing laws which violate established constitutional rules and threaten individual rights.

In that sense, judicial review is “conservative.” Judicial review is not intended to have five unelected judges decree a novel constitutional order by overturning long-established laws. That is the function of lawmakers in legislatures or constitutional conventions. Yet, the Supreme Court at times has taken on that function by discovering fanciful, previously unheard-of constitutional meaning in ambiguous clauses. These discoveries typically reflect the views of a narrow socio-political elite more than those of the citizenry at large. An ideologically committed minority faction is thus able to impose its utopian vision on the majority.

One can easily come up with more examples of current functional weaknesses and dysfunctions in the constitutional system described by the writers of The Federalist. The Anti-federalists broadly predicted many of the current developments, although it is to be doubted that their proposals, to the extent they had any, would have worked better to preserve the republican nature of the original order. Nor is it to be understood that all changes are necessarily bad. One might well agree with the social benefit of some of the constitutional innovations from the Supreme Court, yet be concerned about the way in which those changes came about. One might accept that some of the actions of the unelected agencies have been for the public good, yet worry about the threat to republican self-government posed by the bureaucratic state of self-declared “experts.” One might favor certain policies enacted into law by Congress, yet question the desirability of a system which increasingly micromanages life from thousands of miles away.

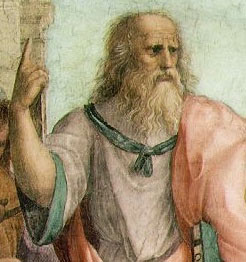

There are many ominous signs which suggest that we have lost our republican form of government as envisioned by the Framers. What we have left, it often appears, are certain trappings and rituals, much as happened with the Roman senate and other republican institutions during the Roman Empire and beyond. Perhaps the classic expositors of republics were right, that such a form of government cannot exist over a large area with many diverse groups of people. Perhaps Madison’s faith in the representative system was shaped by an implicit acceptance of the Aristotelian assumption that self-government was possible only in a community small enough that one could speak of “friendship.” There was much debate among classic writers about the size limits of community. One person did not make a polis. With 100,000, one no longer had a polis. At the time of the Philadelphia Convention, the largest state, Virginia, had a population over 800,000, including slaves. The next largest, Pennsylvania, had under 500,000. The debate over proper-sized districts for the House of Representatives, the most “republican” part of the government, settled the number at 30,000 residents per representative. The Anti-federalists challenged this ratio as too high and unrepublican by pointing out that in Pennsylvania’s state legislature, the ratio was one representative for each four to five thousand residents. Madison replied in essay No. 55 that the House of Representatives would only deal with national matters which do not require particular knowledge of local affairs or connection to specific local sentiments. Today, each congressional district approaches the then-population of Virginia, and the Congress regularly passes laws which have profound local effects. Whether or not Aristotle was correct about the precise limits of “community,” surely it beggars belief to say that today’s congressional districts are republican in anything but name.

Long tenures in office were another danger, according to republicans. The Articles of Confederation limited the number of terms a member of Congress could serve. The Constitution does not. Hence it is common for representatives to spend decades in office, which results in part from the difficulty of ousting incumbents in large districts gerrymandered to protect them. It is problematic to claim that such effective life tenures are “republican.”

Another important role in republican systems is played by various non-governmental social associations, such as the family, religious institutions, unions, and charitable groups. The 18th-century Anglo-Irish philosopher and politician Edmund Burke centered his theory of constitutional stability on the vitality of such institutions, which represent tradition and continuity and thereby guard against radicalism and turmoil. Burke was quite familiar to Americans for his vindications of their political claims before and during the Revolutionary War. He contrasted the stability of the English constitutional system with the situation in France. He was horrified by the violence of the French Revolution which grew from its utopian radicalism. It is inevitably the object of totalitarian governments to destroy or subjugate such intermediary institutions which threaten the power of the state over the people.

One must consider, then, some uncomfortable topics. To what extent has the American family structure been undermined by divorce, single parenthood, and various incentives created through the welfare state? How significant are religious institutions in the life of Americans today compared with preceding generations? With the exception of public employee unions, how significant are labor unions today? The same question must be asked about the vitality of local business associations and related service clubs, which played such significant roles in communities in the past.

The great Northwest Ordinance of 1787 declared, “Religion, morality, and knowledge being necessary to good government and the happiness of mankind, schools, and the means of education shall forever be encouraged.” This goal reflects the inculcation of private virtue which the different groups of American republicans agreed were a necessary basis for the preservation of republican government, even if some argued that it was not a sufficient basis. Are educational institutions fulfilling their task of teaching the heritage, morals, and substantive knowledge upon which the founding generation staked the success of their republic, or has the radicals’ long march through those institutions corrupted that mission?

Is the current dynamic of identity politics leading us to a dangerous tribalism which tears the social bonds necessary for a stable and peaceful community? If factions are the bane of republican systems, will the stress of this anarchic impetus ultimately lead to a collapse into the tyranny which the Anti-federalists feared?

If freedom of the press is needed for “republican form of government,” are the media providing useful information to the public or at least performing their self-appointed task of bravely and indiscriminately “speaking truth to power”? Or have they become so ideologically blinded to convince themselves of the righteousness of their quest to indoctrinate the public, that they have vindicated Thomas Jefferson’s indictment of the press in his 1807 letter to John Norvell, “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper. Truth itself becomes suspicious by being put into that polluted vehicle….The man who never looks into a newspaper is better informed than he who reads them, inasmuch as he who knows nothing is nearer to truth than he whose mind is filled with falsehoods and errors.”

Many of these dysfunctions were spawned by utopian schemers who without thought or hesitation cast aside rules and institutions forged in human experience. They failed to heed G.K. Chesterton’s warning in his parable of the fence built across a road not to tear it down until one clearly understands why it was erected in the first place.

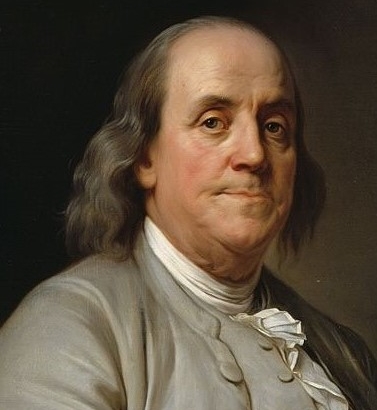

As explored over these 90 sessions, the Constitution’s drafters constructed a framework of republican government and the means to preserve it. The structural components of the system, functioning as intended, assist that task. However, the Framers understood their own fallibility and the fragility of their creation. The Constitution is just a parchment. To give it life requires the attention of a civically militant citizenry committed to the preservation and functioning of its parts. That is the politics of the true “living constitution.” And, as has been said, politics is downstream from culture. The French philosopher Joseph de Maistre pungently observed, “Every nation gets the government it deserves.” Although his comment was about Russia, it would have particular relevance for a republic. Likewise, in his famous aphorism, Benjamin Franklin did not just say to Mrs. Elizabeth Powel that the convention had produced a republic. He added, wittily but ominously, “if you can keep it.” The question is whether the American people continue to be up to the challenge.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg_trials#/media/File:Color_photograph_of_judges'_bench_at_IMT.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nuremberg_trials#/media/File:Color_photograph_of_judges'_bench_at_IMT.jpg Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

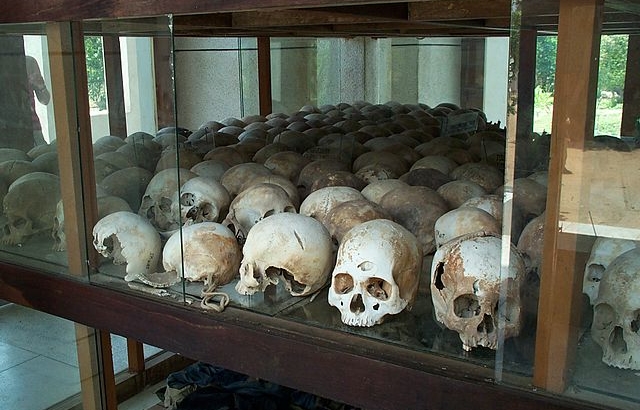

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clive.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clive.jpg James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also a member of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also a member of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:Battle_of_Waterloo_1815.PNG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:Battle_of_Waterloo_1815.PNG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Peace_Conference_(1919%E2%80%931920)#/media/File:William_Orpen_%E2%80%93_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors,_Versailles_1919,_Ausschnitt.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Peace_Conference_(1919%E2%80%931920)#/media/File:William_Orpen_%E2%80%93_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors,_Versailles_1919,_Ausschnitt.jpg Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/League_of_Nations#/media/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/League_of_Nations#/media/File:No-nb_bldsa_5c006.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headquarters_of_the_United_Nations#/media/File:UN_Members_Flags2.JPG

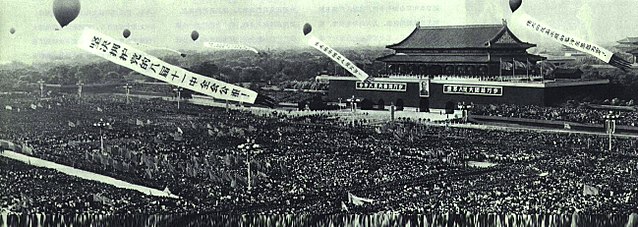

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Headquarters_of_the_United_Nations#/media/File:UN_Members_Flags2.JPG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1967-03_1966%E5%B9%B412%E6%9C%8826%E6%97%A5%E6%B1%9F%E9%9D%92%E5%91%A8%E6%81%A9%E6%9D%A5%E5%BA%B7%E7%94%9F%E6%8E%A5%E8%A7%81%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1967-03_1966%E5%B9%B412%E6%9C%8826%E6%97%A5%E6%B1%9F%E9%9D%92%E5%91%A8%E6%81%A9%E6%9D%A5%E5%BA%B7%E7%94%9F%E6%8E%A5%E8%A7%81%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg Dave Kopel

Dave Kopel https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B49%E6%9C%8815%E6%97%A5%E5%A4%A9%E5%AE%89%E9%97%A8%E6%B8%B8%E8%A1%8C-%E5%85%AB%E5%B1%8A%E5%8D%81%E4%B8%80%E4%B8%AD.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_Revolution#/media/File:1966-11_1966%E5%B9%B4%E6%AF%9B%E6%B3%BD%E4%B8%9C%E6%9E%97%E5%BD%AA%E4%B8%8E%E7%BA%A2%E5%8D%AB%E5%85%B5.jpg

Jeanne McKinney is an award-winning writer whose focus and passion is our United States active-duty military members and military news. Her Patriot Profiles offer an inside look at the amazing active-duty men and women in all Armed Services, including U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, Air Force, Coast Guard, and National Guard. Reporting includes first-hand accounts of combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the fight against violent terror groups, global defense, tactical training and readiness, humanitarian and disaster relief assistance, next-generation defense technology, family survival at home, U.S. port and border protection and illegal immigration, women in combat, honoring the Fallen, Wounded Warriors, Military Working Dogs, Crisis Response, and much more. Starting in 2012, McKinney has won multiple San Diego Press Club “Excellence in Journalism Awards,” including eight “First Place” honors, as well as multiple second and third place recognition for her Patriot Profiles published printed articles. Including awards for Patriot Profiles military films. During the year 2020, McKinney has written and published dozens of investigative articles in her ongoing fight to preserve America the Republic, the Constitution, and its laws. One such story was selected for use in a legal brief in the national fight for 2020 election integrity.

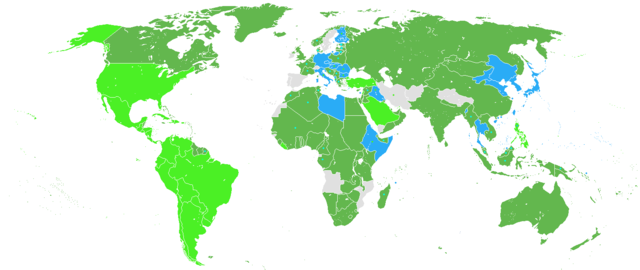

Jeanne McKinney is an award-winning writer whose focus and passion is our United States active-duty military members and military news. Her Patriot Profiles offer an inside look at the amazing active-duty men and women in all Armed Services, including U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, Air Force, Coast Guard, and National Guard. Reporting includes first-hand accounts of combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the fight against violent terror groups, global defense, tactical training and readiness, humanitarian and disaster relief assistance, next-generation defense technology, family survival at home, U.S. port and border protection and illegal immigration, women in combat, honoring the Fallen, Wounded Warriors, Military Working Dogs, Crisis Response, and much more. Starting in 2012, McKinney has won multiple San Diego Press Club “Excellence in Journalism Awards,” including eight “First Place” honors, as well as multiple second and third place recognition for her Patriot Profiles published printed articles. Including awards for Patriot Profiles military films. During the year 2020, McKinney has written and published dozens of investigative articles in her ongoing fight to preserve America the Republic, the Constitution, and its laws. One such story was selected for use in a legal brief in the national fight for 2020 election integrity. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allies_of_World_War_II#/media/File:Map_of_participants_in_World_War_II.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allies_of_World_War_II#/media/File:Map_of_participants_in_World_War_II.png Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German-occupied_Europe#/media/File:Europe_under_Nazi_domination.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German-occupied_Europe#/media/File:Europe_under_Nazi_domination.png

Patrick Garry is professor of law at the University of South Dakota and is the author of Limited Government and the Bill of Rights and The False Promise of Big Government: How Washington Helps the Rich and Hurts the Poor.

Patrick Garry is professor of law at the University of South Dakota and is the author of Limited Government and the Bill of Rights and The False Promise of Big Government: How Washington Helps the Rich and Hurts the Poor.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodrow_Wilson#/media/File:Congress_opening_message_63rd_02406a.tif

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Woodrow_Wilson#/media/File:Congress_opening_message_63rd_02406a.tif Will Morrisey is Professor Emeritus of Politics at Hillsdale College, and Editor and Publisher of Will Morrisey Reviews.

Will Morrisey is Professor Emeritus of Politics at Hillsdale College, and Editor and Publisher of Will Morrisey Reviews. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Croly

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Croly https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinnytsia_massacre#/media/File:Vinnycia16.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinnytsia_massacre#/media/File:Vinnycia16.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin#/media/File:Stalin_1920-1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Stalin#/media/File:Stalin_1920-1.jpg Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird.

Eric Wise is a partner in the law firm of Alston & Bird. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_in_World_War_I#/media/File:US_64th_regiment_celebrate_the_Armistice.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_in_World_War_I#/media/File:US_64th_regiment_celebrate_the_Armistice.jpg Stephen Tootle is a Professor of History at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia, California and Honored Visiting Graduate Faculty in History and Government at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio. His writings have appeared in National Review, Presidential Studies Quarterly, The Claremont Review of Books, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, and other publications. He gives talks on politics and political history for the Ashbrook Center and the Bill of Rights Institute and is the co-host of The Paper Trail Podcast, a weekly public affairs podcast published by the Sun-Gazette.

Stephen Tootle is a Professor of History at the College of the Sequoias in Visalia, California and Honored Visiting Graduate Faculty in History and Government at Ashland University in Ashland, Ohio. His writings have appeared in National Review, Presidential Studies Quarterly, The Claremont Review of Books, The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era, and other publications. He gives talks on politics and political history for the Ashbrook Center and the Bill of Rights Institute and is the co-host of The Paper Trail Podcast, a weekly public affairs podcast published by the Sun-Gazette. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_monitor_Sava#/media/File:SS_Bodrog_1914.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_monitor_Sava#/media/File:SS_Bodrog_1914.jpg Thomas Bruscino is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the United States Army War College. He holds a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio University and has been a historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington, DC and the US Army Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, and a professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. He is the author of A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along(University of Tennessee Press, 2010), and Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare (CSI Press, 2006), and numerous book chapters. His writings have appeared in the Claremont Review of Books, Army History, The New Criterion, Military Review, The Journal of Military History, White House Studies, War & Society, War in History, The Journal of America’s Military Past, Infinity Journal, Doublethink, Reviews in American History, Joint Force Quarterly, and Parameters.

Thomas Bruscino is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the United States Army War College. He holds a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio University and has been a historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington, DC and the US Army Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, and a professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. He is the author of A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along(University of Tennessee Press, 2010), and Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare (CSI Press, 2006), and numerous book chapters. His writings have appeared in the Claremont Review of Books, Army History, The New Criterion, Military Review, The Journal of Military History, White House Studies, War & Society, War in History, The Journal of America’s Military Past, Infinity Journal, Doublethink, Reviews in American History, Joint Force Quarterly, and Parameters.

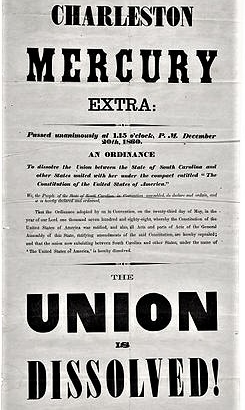

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Charleston_Mercury_Secession_Broadside,_1860.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Charleston_Mercury_Secession_Broadside,_1860.jpg Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of

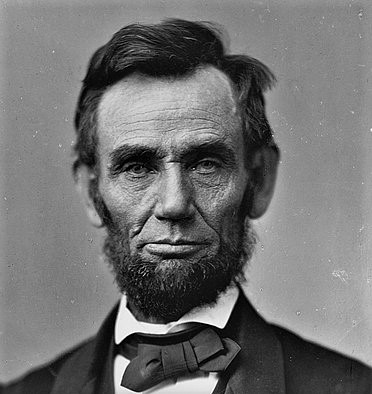

Samuel Postell serves as Executive Director of  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Lincoln#/media/File:Abraham_Lincoln_O-77_matte_collodion_print.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abraham_Lincoln#/media/File:Abraham_Lincoln_O-77_matte_collodion_print.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Bombardment_of_Fort_Sumter.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Civil_War#/media/File:Bombardment_of_Fort_Sumter.jpg Eric C. Sands is Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at Berry College. He has written a book on Abraham Lincoln and edited a second volume on political parties. His teaching and research interests focus on constitutional law, American political thought, the founding, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and political parties.

Eric C. Sands is Associate Professor of Political Science and International Affairs at Berry College. He has written a book on Abraham Lincoln and edited a second volume on political parties. His teaching and research interests focus on constitutional law, American political thought, the founding, the Civil War and Reconstruction, and political parties.  https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Ereignisblatt_aus_den_revolution%C3%A4ren_M%C3%A4rztagen_18.-19._M%C3%A4rz_1848_mit_einer_Barrikadenszene_aus_der_Breiten_Strasse,_Berlin_01.jpg

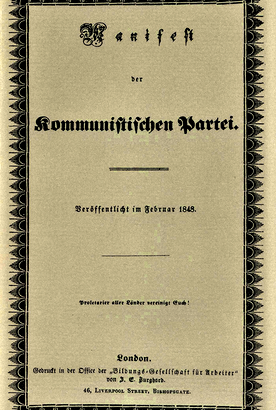

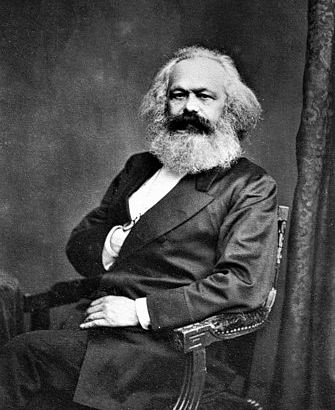

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Ereignisblatt_aus_den_revolution%C3%A4ren_M%C3%A4rztagen_18.-19._M%C3%A4rz_1848_mit_einer_Barrikadenszene_aus_der_Breiten_Strasse,_Berlin_01.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Communist-manifesto.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Communist-manifesto.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Napoleon_sainthelene.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Napoleon_sainthelene.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Bouchot_-_Le_general_Bonaparte_au_Conseil_des_Cinq-Cents.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Bouchot_-_Le_general_Bonaparte_au_Conseil_des_Cinq-Cents.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Jacques-Louis_David_-_The_Emperor_Napoleon_in_His_Study_at_the_Tuileries_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Jacques-Louis_David_-_The_Emperor_Napoleon_in_His_Study_at_the_Tuileries_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg Adam M. Carrington is an Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College. There, he teaches on matters of Constitutional law, American political institutions, and separation of powers. His writing has appeared in such popular forums as The Wall Street Journal, The Hill, National Review, and Washington Examiner. His book on the jurisprudence of Justice Stephen Field was published in 2017 by Lexington. Carrington received his B.A. from Ashland University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Baylor University. He lives in Hillsdale with his wife and their two daughters.

Adam M. Carrington is an Associate Professor of Politics at Hillsdale College. There, he teaches on matters of Constitutional law, American political institutions, and separation of powers. His writing has appeared in such popular forums as The Wall Street Journal, The Hill, National Review, and Washington Examiner. His book on the jurisprudence of Justice Stephen Field was published in 2017 by Lexington. Carrington received his B.A. from Ashland University and his M.A. and Ph.D. from Baylor University. He lives in Hillsdale with his wife and their two daughters.

Daniel A. Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

Daniel A. Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:Evacuation_Day_and_Washington's_Triumphal_Entry.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:Evacuation_Day_and_Washington's_Triumphal_Entry.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Burke#/media/File:EdmundBurke1771.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Edmund_Burke#/media/File:EdmundBurke1771.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Francis_Mercer#/media/File:Gov._John_Francis_Mercer_-_Robert_Field_1803.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Francis_Mercer#/media/File:Gov._John_Francis_Mercer_-_Robert_Field_1803.jpg Andrea Criswell is a wife and mother of four, who teaches homeschool students in northwest Houston. A graduate of Texas Tech University and Asbury Theological Seminary, she teaches Christian Worldview classes, high school biology and a love for the United States Constitution.

Andrea Criswell is a wife and mother of four, who teaches homeschool students in northwest Houston. A graduate of Texas Tech University and Asbury Theological Seminary, she teaches Christian Worldview classes, high school biology and a love for the United States Constitution.

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Writing_the_Declaration_of_Independence_1776_cph.3g09904.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Writing_the_Declaration_of_Independence_1776_cph.3g09904.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirteen_Colonies#/media/File:Thirteencolonies_politics_cropped.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirteen_Colonies#/media/File:Thirteencolonies_politics_cropped.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Colony#/media/File:Landing-Bacon.PNG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plymouth_Colony#/media/File:Landing-Bacon.PNG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Model_of_Christian_Charity#/media/File:John_Winthrop.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/A_Model_of_Christian_Charity#/media/File:John_Winthrop.jpg Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America, with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Civil_War#/media/File:Battle_of_Naseby.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/English_Civil_War#/media/File:Battle_of_Naseby.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%86thelstan#/media/File:Painting,_Beverley_Minster_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1317269.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%86thelstan#/media/File:Painting,_Beverley_Minster_-_geograph.org.uk_-_1317269.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

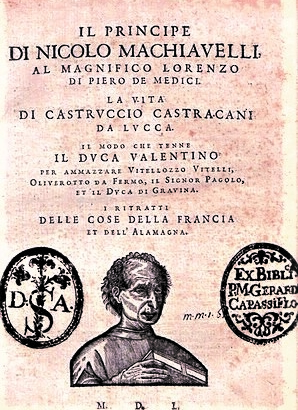

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Prince#/media/File:Machiavelli_Principe_Cover_Page.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Prince#/media/File:Machiavelli_Principe_Cover_Page.jpg Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_di_Bicci_de%27_Medici#/media/File:Giovanni_di_Bicci_de'_Medici.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giovanni_di_Bicci_de%27_Medici#/media/File:Giovanni_di_Bicci_de'_Medici.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utrecht#/media/File:Lambert_de_Hondt_(II)_-_The_Surrender_of_Utrecht.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utrecht#/media/File:Lambert_de_Hondt_(II)_-_The_Surrender_of_Utrecht.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Maurits_(1567-1625),_prins_van_Oranje,_in_de_slag_bij_Nieuwpoort_(1600).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Maurits_(1567-1625),_prins_van_Oranje,_in_de_slag_bij_Nieuwpoort_(1600).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Veen01.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Veen01.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Years%27_War#/media/File:Siege_of_Namur_(1692).JPG

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nine_Years%27_War#/media/File:Siege_of_Namur_(1692).JPG https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Diet_(Holy_Roman_Empire)#/media/File:Luther_(Wislicenus).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Diet_(Holy_Roman_Empire)#/media/File:Luther_(Wislicenus).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crown_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire#/media/File:Holy_Roman_Empire_Crown_(Imperial_Treasury)2.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crown_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire#/media/File:Holy_Roman_Empire_Crown_(Imperial_Treasury)2.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_Arsenal#/media/File:Campo_de_l'Arsenal.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_Arsenal#/media/File:Campo_de_l'Arsenal.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Venitian_ford_at_Navlion.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Venitian_ford_at_Navlion.jpg Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Archive-ugent-be-79D46426-CC9D-11E3-B56B-4FBAD43445F2_DS-240_(cropped).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Archive-ugent-be-79D46426-CC9D-11E3-B56B-4FBAD43445F2_DS-240_(cropped).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Q._Servilius_Caepio_(M._Junius)_Brutus,_denarius,_54_BC,_RRC_433-1_reverse.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Q._Servilius_Caepio_(M._Junius)_Brutus,_denarius,_54_BC,_RRC_433-1_reverse.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Forum_Romanum_through_Arch_of_Septimius_Severus_Forum_Romanum_Rome.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Forum_Romanum_through_Arch_of_Septimius_Severus_Forum_Romanum_Rome.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism#/media/File:Paolo_Monti_-_Servizio_fotografico_(Napoli,_1969)_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism#/media/File:Paolo_Monti_-_Servizio_fotografico_(Napoli,_1969)_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg