Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

“To suppress Enquiries into the Administration is good Policy in an arbitrary Government: But a free Constitution and freedom of Speech have such a reciprocal Dependence on each other that they cannot subsist without consisting together.” – Pennsylvania Gazette, November 17, 1737, printed by Benjamin Franklin, later reprinted in the Barbados Gazette, 1738, and attributed to Andrew Hamilton, a Pennsylvania Colonial Representative, and lawyer who defended John Peter Zenger who was arrested for criticizing the government, as having possibly been the author of the article.

The age-old proclamation made in the Pennsylvania Gazette, attributed to Andrew Hamilton, regarding the “reciprocal dependence” between the United States Constitution and free speech, resonates powerfully with the principles held dear by anyone deeply concerned with balance of power between individuals and their government: the inseparability of a free constitution and freedom of speech. For a republican form of government to remain genuinely representative, it is imperative to ensure that citizens can air their grievances without fear of retaliation. To suppress the voice of the people is, in effect, to suppress the very essence of democracy which is the means a representative republic uses to make apparent the consent of the governed.

At the heart of a representative government lies the principle that those in power are there to serve, and not to dictate. They are but emissaries, chosen by the populace to voice their hopes, aspirations, and concerns. Such representation is hollow if the populace cannot, or is afraid to, communicate openly.

Civil discourse, which is simply the ability to discuss and debate matters of public interest in a reasoned and respectful manner, is the bedrock upon which representative government stands. Without it, the bridge between the representatives and those they represent is broken. The essence of representative government is lost if its constituents cannot engage in free discourse without fear of persecution.

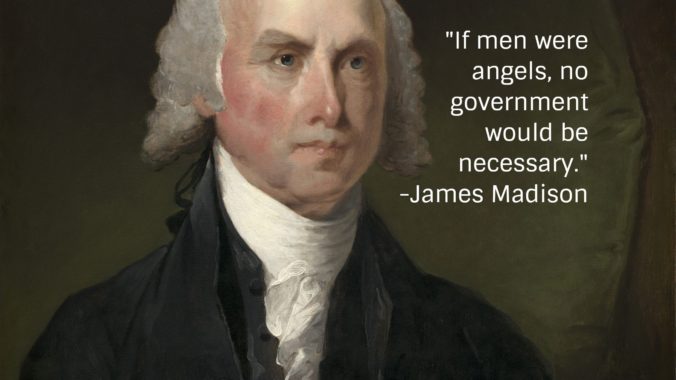

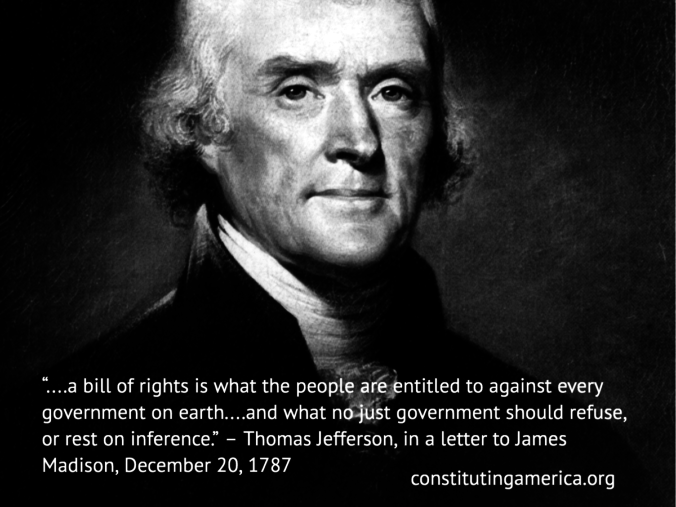

Traditionally, classical liberals (which is how one can describe most, if not all, of the founding fathers) firmly believe in the principle of minimal government intervention in the lives of its citizens. Freedom of speech, as a cornerstone of liberty, is not just the ability to speak one’s mind but to do so without fear of government retribution. To silence or suppress speech is to curb the very freedom that serves as a bulwark against tyranny.

The case of John Peter Zenger, defended by Andrew Hamilton, stands as a testament to the dangers of a government that seeks to stifle criticism. Arrested for merely voicing his critique of the establishment, Zenger’s plight underscores the importance of preserving unhindered freedom of speech. When governments are allowed to decide what can and cannot be said, we tread perilously close to the realms of despotism.

The quote from the Pennsylvania Gazette highlights a profound truth: a free constitution and freedom of speech are interdependent. Without the liberty to speak one’s mind, a constitution, however free in letter, becomes tyrannical in spirit. Conversely, freedom of speech without a constitution that protects and upholds it is but an illusion.

The reason for this reciprocal relationship is clear. A free constitution provides the framework within which rights, including freedom of speech, are preserved. Meanwhile, unhindered freedom of speech ensures that this constitution remains truly representative, constantly held to account by the voice of the people.

In an age where voices are increasingly stifled under the guise of various reasons, it is paramount to remember the wisdom of yesteryears, as echoed by Andrew Hamilton. To suppress inquiries into administration might be the hallmark of autocracy, but in representative government, the voice of the people must remain unbridled and unbroken.

In any dynamic society that prides itself on progress, innovation, and the welfare of its people, the free flow and exchange of ideas is not just a luxury, but an absolute necessity. The significance of this cannot be overstated, particularly when it comes to addressing and solving the myriad problems society faces. At their core, the principles upon which this nation was founded cherish the values of individual freedom, limited government, and the sanctity of personal choice. This philosophy acknowledges that every individual, with their unique experiences and perspectives, has the capacity to contribute to the vast tapestry of human knowledge. However, this can only be realized if they are allowed and encouraged to express themselves freely, even if their ideas are unpopular or deemed contentious.

At the foundation of the free exchange of ideas is the belief in the “marketplace of ideas,” a theory that the truth will emerge from the competition of ideas in free, transparent public discourse. Just as economic markets rely on competition to produce the best goods and services, intellectual progress requires a contest of ideas. Suppressing unpopular or controversial ideas, even those deemed false or harmful, doesn’t necessarily make them disappear. Instead, it drives them underground where they are not subject to public scrutiny, critique, and potential refutation.

Moreover, it creates a “marketplace of ideas.” Many of the most groundbreaking discoveries and social movements in history were once viewed as controversial or even heretical. Galileo’s heliocentric model and the rights of women to vote were both, at different times, unpopular ideas. Without the freedom to challenge prevailing notions and the status quo, society would stagnate, and advancement would be hindered. A society that is open to the free exchange of ideas is more adaptable, resilient, and inventive.

Free speech also offers protection from despotism and tyranny. One of the most potent tools at the disposal of tyrannical regimes is the suppression of speech and the curtailment of the free exchange of ideas. By controlling the narrative and silencing dissent, these regimes can maintain power and perpetuate their ideologies unchallenged. History has repeatedly shown the dangers of this approach. Protecting even unpopular speech ensures a check against potential governmental overreach and tyranny.

One can also not understate the importance of freedom of speech to the betterment of men and women themselves, outside of just the political realm. On an individual level, exposure to a wide array of ideas, even those that challenge our deeply held beliefs, is essential for personal growth. It encourages critical thinking, promotes empathy by understanding various perspectives, and enriches our knowledge base. Suppressing unpopular speech denies individuals these opportunities. Promoting the greatest amount of speech ensures a vibrant civil society.

The freest speech also is a way to ensure that society solves its own problems. No society is without its problems, and often, it is only through open dialogue and the free exchange of ideas that these issues come to light. Unpopular speech can draw attention to overlooked issues, catalyze movements for change, and present alternative solutions to pervasive problems. Silencing such speech, on the other hand, can perpetuate ignorance and hinder society’s ability to address its challenges.

The suppression of speech, particularly when it involves the silencing of religious or ethnic expressions, can have dire consequences on societal cohesion and stability. Yugoslavia, under its Communist regime, is a poignant example of this phenomenon. The country, a mosaic of ethnicities and religions, was kept together through strong centralized governance and strict control over nationalist sentiments. The Communist authorities aimed to forge a unified Yugoslav identity, which involved suppressing religious and nationalist expression, relegating it to the private sphere, and often demonizing it in the public sphere. This suppression did not eradicate the deeply-rooted ethnic and religious sentiments; rather, it drove them underground, where they festered, accumulated grievances, and lacked the necessary open space for dialogue and reconciliation.

When the Communist regime in Yugoslavia disintegrated in the early 1990s, the suppressed sentiments and grievances came to the surface with a vengeance. Without the structures or platforms for peaceful dialogue in place, these sentiments exploded into sectarian violence, leading to a series of brutal wars that resulted in the dissolution of Yugoslavia. Had there been a more open space for religious and ethnic expression during the Communist era, communities might have had the opportunities to address and possibly reconcile their differences or at least coexist peacefully. Instead, the suppression created a vacuum, and when the lid was abruptly removed, the pent-up frustrations and hostilities were unleashed in a tragic wave of violence. This serves as a powerful reminder of the dangers inherent in suppressing speech and the importance of fostering open dialogue in multi-ethnic and multi-religious societies.

The importance of the free flow and exchange of ideas, even those that are unpopular, cannot be emphasized enough. Such freedom is at the very core of a thriving, advancing society. In embracing the free exchange of ideas, the fundamental human right to express oneself is championed, and fostered is an environment ripe for innovation and the holistic betterment of society.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, a Fellow with Constituting America, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty, a Fellow with Constituting America, as well as Chairman and Founder of the Institute for Regulatory Analysis and Engagement. IFL is a non-profit advocacy organization focused on advancing free-market and limited government principles into public policy at all levels. IRAE is a non-profit academic and activist organization whose mission is to examine regulations and regulatory proposals, assess their economic and societal impacts, and offer expert commentary in order to create better public policies. Andrew has been involved in free-market and limited-government causes for more than 25 years, has testified before Congress nearly two dozen times, spoken to audiences across the United States, and has taught at the collegiate level.

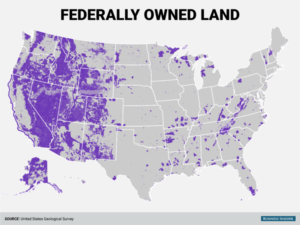

A globally-recognized expert on the impact of regulation on business, Andrew is regularly called on to offer innovative solutions to the challenges of squaring public policy priorities with the impact and efficacy of those policies, as well as their unintended consequences. Prior to becoming President of IFL and founding IRAE, he was the principal regulatory affairs lobbyist for the National Federation of Independent Business, the nation’s largest small business association. As President of the Institute for Liberty, he became recognized as an expert on the Constitution, especially issues surrounding private property rights, free speech, abuse of power, and the concentration of power in the federal executive branch.

Andrew has had an extensive career in media—having appeared on television programs around the world. From 2017 to 2021, he hosted a highly-rated weekly program on WBAL NewsRadio 1090 in Baltimore (as well as serving as their principal fill-in host from 2011 until 2021), and has filled in for both nationally-syndicated and satellite radio programs. He also created and hosted several different podcasts—currently hosting Andrew and Jerry Save The World, with long-time colleague, Jerry Rogers.

He holds a Master’s Degree in Public Administration from Troy University and his degree from William & Mary is in International Relations.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Peace_Conference_(1919%E2%80%931920)#/media/File:William_Orpen_%E2%80%93_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors,_Versailles_1919,_Ausschnitt.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Peace_Conference_(1919%E2%80%931920)#/media/File:William_Orpen_%E2%80%93_The_Signing_of_Peace_in_the_Hall_of_Mirrors,_Versailles_1919,_Ausschnitt.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinnytsia_massacre#/media/File:Vinnycia16.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vinnytsia_massacre#/media/File:Vinnycia16.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Ereignisblatt_aus_den_revolution%C3%A4ren_M%C3%A4rztagen_18.-19._M%C3%A4rz_1848_mit_einer_Barrikadenszene_aus_der_Breiten_Strasse,_Berlin_01.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Communist_Manifesto#/media/File:Ereignisblatt_aus_den_revolution%C3%A4ren_M%C3%A4rztagen_18.-19._M%C3%A4rz_1848_mit_einer_Barrikadenszene_aus_der_Breiten_Strasse,_Berlin_01.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirteen_Colonies#/media/File:Thirteencolonies_politics_cropped.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirteen_Colonies#/media/File:Thirteencolonies_politics_cropped.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utrecht#/media/File:Lambert_de_Hondt_(II)_-_The_Surrender_of_Utrecht.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Utrecht#/media/File:Lambert_de_Hondt_(II)_-_The_Surrender_of_Utrecht.jpg

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty. Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.