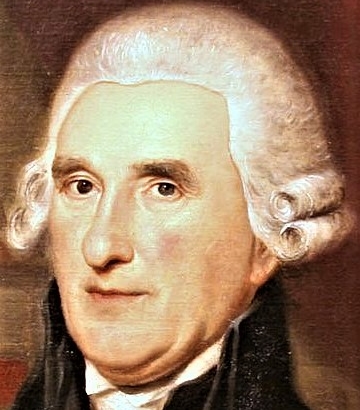

Thomas McKean (1734-1817) was born of Scotch-Irish ancestry in New London, eastern Pennsylvania near the border of New Jersey and Delaware. He married Mary Borden with whom he had six children. Mary was the sister of Francis Hopkinson’s wife. Hopkinson was a signer from New Jersey. After Mary died, McKean married Sarah Armitage and together they had five children.

McKean practiced law in both Pennsylvania and Delaware, and served as a colonel in the New Jersey militia. He was politically active in all three states, even while elected to federal office. In 1756, he became deputy Attorney General in Pennsylvania. In 1757, he was admitted to the Bar of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and appointed clerk of the Delaware Assembly.

In 1762, the Assembly appointed McKean and Caesar Rodney, another signer of the Declaration of Independence, to revise and publish the laws of the province of Delaware. Also in 1762, he was elected to the Delaware Assembly, and re-elected for seventeen years despite a six-year residence in Philadelphia during that time. No other Signer of the Declaration took part in so many different State activities simultaneously as did McKean.

In 1775, he represented Delaware at the Stamp Act Congress in New York and then Pennsylvania at the Continental Congress from 1774-1777. On July 1, 1776, two of the three Delaware delegates were in attendance. McKean voted in favor of Independence and George Read voted against it. McKean strongly opposed the power that the British were imposing upon the colonies. He sent an urgent message to Caesar Rodney in Dover to come at once to Philadelphia to break the deadlock. Rodney rode overnight in a rainstorm, having arrived wearing boots and spurs as described by McKean, and the deadlock was broken on July 2.

McKean also served on the Congressional committee that drafted the Articles of Confederation. In 1777, he was appointed Chief Justice of Pennsylvania, an office that he held for nearly twenty years. He was elected President of the Continental Congress in 1781. In 1787, he attended the Pennsylvania ratifying convention and voted in favor of ratification. In 1789, he was elected Governor of Pennsylvania and served in that office before retiring in 1812, but his governorship was controversial as he survived an impeachment effort due to strife within differing partisan viewpoints.

Toward the end of his life, though McKean had mostly retired, he participated in a discussion to guard against possible British invasion of Philadelphia in the War of 1812. McKean admonished the people to set aside differences and consider there were only two parties which consisted of America and its invaders.

McKean died in Philadelphia on June 24, 1817 at the age of 83.

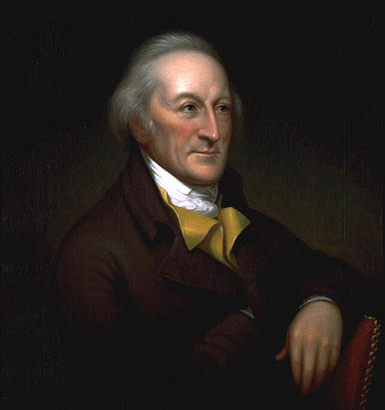

Gordon Lloyd is the Robert and Katheryn Dockson Professor of Public Policy at Pepperdine University, and a Senior Fellow at the Ashbrook Center. He earned his bachelor of arts degree in economics and political science at McGill University. He completed all the course work toward a doctorate in economics at the University of Chicago before receiving his master of arts and PhD degrees in government at Claremont Graduate School. The coauthor of three books on the American founding and sole author of a book on the political economy of the New Deal, he also has numerous articles, reviews, and opinion-editorials to his credit. His latest coauthored book, The New Deal & Modern American Conservatism: A Defining Rivalry, was published in 2013, and he most recently released as editor, Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, in September 2014. He is the creator, with the help of the Ashbrook Center, of four highly regarded websites on the origin of the Constitution. He has received many teaching, scholarly, and leadership awards including admission to Phi Beta Kappa and the Howard White Award for Teaching Excellence at Pepperdine University. He currently serves on the National Advisory Council for the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Presidential Learning Center through the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation.

Gordon Lloyd is the Robert and Katheryn Dockson Professor of Public Policy at Pepperdine University, and a Senior Fellow at the Ashbrook Center. He earned his bachelor of arts degree in economics and political science at McGill University. He completed all the course work toward a doctorate in economics at the University of Chicago before receiving his master of arts and PhD degrees in government at Claremont Graduate School. The coauthor of three books on the American founding and sole author of a book on the political economy of the New Deal, he also has numerous articles, reviews, and opinion-editorials to his credit. His latest coauthored book, The New Deal & Modern American Conservatism: A Defining Rivalry, was published in 2013, and he most recently released as editor, Debates in the Federal Convention of 1787, in September 2014. He is the creator, with the help of the Ashbrook Center, of four highly regarded websites on the origin of the Constitution. He has received many teaching, scholarly, and leadership awards including admission to Phi Beta Kappa and the Howard White Award for Teaching Excellence at Pepperdine University. He currently serves on the National Advisory Council for the Walter and Leonore Annenberg Presidential Learning Center through the Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor