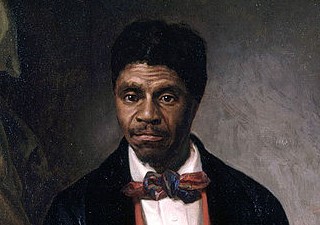

March 6, 1857: Landmark Supreme Court Decision of Dred Scott, Grounds of Race Whether Free or Slave

In 1834, Dr. Emerson, an Army surgeon, took his slave Dred Scott from Missouri, a slave state, to Illinois, a free state, and then, in 1836, to Fort Snelling in Wisconsin Territory. The latter was north of the geographic line at latitude 36°30′ established under the Missouri Compromise of 1820 as the division between free territory and that potentially open to slavery. In addition, the law that organized Wisconsin Territory in 1836 made the domain free. Emerson, his wife, and Scott and his family eventually returned to Missouri by 1840. Emerson died in Iowa in 1843. Ownership of Scott and his family ultimately passed to Emerson’s brother-in-law, John Sanford, of New York.

With financial assistance from the family of his former owner, the late Peter Blow, Scott sued for his freedom in Missouri state court, beginning in 1846. He argued that he was free due to having resided in both a free state and a free territory. After some procedural delays, the lower court jury eventually agreed with him in 1850, but the Missouri Supreme Court in 1852 overturned the verdict. The judges rejected Scott’s argument, on the basis that the laws of Illinois and Wisconsin Territory had no extraterritorial effect in Missouri once he returned there.

It has long been speculated that the case was contrived. Records were murky, and it was not clear that Sanford actually owned Scott. Moreover, Sanford’s sister Irene, the late Dr. Emerson’s widow, had remarried an abolitionist Congressman. Finally, the suit was brought in the court of Judge Alexander Hamilton, known to be sympathetic to such “freedom suits.”

Having lost in the state courts, in 1853 Scott tried again, in the United States Circuit Court for Missouri, which at that time was a federal trial court. The basic thrust of the case at that level was procedural sufficiency. Federal courts, as courts of limited and defined jurisdiction under Article III of the Constitution, generally can hear only cases between citizens of different states or if a claim is based on a federal statute or treaty, or on the Constitution. There being no federal law of any sort involved, Scott’s claim rested on diversity of citizenship. Scott claimed that he was a free citizen of Missouri and Sanford a citizen of New York. On the substance, Scott reiterated the position from his state court claim. Sanford sought a dismissal on the basis of lack of subject matter jurisdiction because, being black, Scott could not be a citizen of Missouri.

When Missouri sought admission to statehood in 1820, its constitution excluded free blacks from living in the state. The compromise law passed by Congress prohibited the state constitution from being interpreted to authorize a law that would exclude citizens of any state from enjoying the constitutional privileges and immunities of citizenship the state recognized for its own citizens. That prohibition was toothless, and Sanford’s argument rested on Missouri’s negation of citizenship for all blacks. Thus, Scott’s continued status as a slave was not crucial to resolve the case. Rather, his racial status, free or slave, meant that he was not a citizen of Missouri. Thus, the federal court lacked jurisdiction over the suit and could not hear Scott’s substantive claim. Instead, the appropriate forum to determine Scott’s status was the Missouri state court. As already noted, that was a dry well and could not water the fountain of justice.

In a confusing action, the Circuit Court appeared to reject Sanford’s jurisdictional argument, but the jury nevertheless ruled for Sanford on the merits, based on Missouri law. Scott appealed to the United States Supreme Court by writ of error, a broad corrective tool to review decisions of lower courts. The Court heard argument in Dred Scott v. Sandford (the “d” is a clerical error) at its February, 1856, term. The justices were divided on the preliminary jurisdictional issue. They bound the case over to the December, 1856, term, after the contentious 1856 election. There seemed to be a way out of the ticklish matter. In Strader v. Graham in 1850, the unanimous Supreme Court had held that a slave’s status rested finally on the decision of the relevant state court. The justices also had refused to consider independently the claim that a slave became free simply through residence in a free state. Seven of the justices in Dred Scott believed Strader to be on point, and Justice Samuel Nelson drafted an opinion on that basis. Such a narrow resolution would have steered clear of the hot political issue of extension of slavery into new territories that was roiling the political waters and threatening to tear apart the Union.

It was not to be. Several of the Southern justices were sufficiently alarmed by the public debate and affected by sectional loyalty to prepare concurring opinions to address the lurking issue of Scott’s status. Justice James Wayne of Georgia then persuaded his fellows to take up all issues raised by Scott’s suit. Chief Justice Roger Taney would write the opinion.

Writing for himself and six associate justices, Taney delivered the Court’s opinion on March 6, 1857, just a couple of days after the inauguration of President James Buchanan. In his inaugural address, Buchanan hinted at the coming decision through which the slavery question would “be speedily and finally settled.” Apparently having received advance word of the decision, Buchanan declared that he would support the decision, adding coyly, “whatever this may be.” Some historians have wondered if Buchanan actually appreciated the breadth of the Court’s imminent opinion or misunderstood what was about to happen. Of the seven justices that joined the decision that Scott lacked standing to sue and was still a slave, five were Southerners (Taney of Maryland, Wayne, John Catron of Tennessee, Peter Daniel of Virginia, and John Campbell of Georgia). Two were from the North (Samuel Nelson of New York and Robert Grier of Pennsylvania). Two Northerners (Benjamin Curtis of Massachusetts and John McLean of Ohio) dissented.

Taney’s ruling concluded that Scott was not a citizen of the United States, because he was black, and because he was a slave. Thus, the federal courts lacked jurisdiction, and by virtue of the Missouri Supreme Court’s decision, Scott was still a slave. Taney’s argument rested primarily on a complex analysis of citizenship. When the Constitution was adopted, neither slaves nor free blacks were part of the community of citizens in the several states. Thereafter, some states made citizens of free blacks, as they were entitled to do. But that did not affect the status of such individuals in other states, as state laws could not act extraterritorially. Only United States citizenship or state citizenship conferred directly under the Constitution could be the same in all states. Neither slaves nor free blacks were understood to be part of the community of citizens in the states in 1788 when the Constitution was adopted, the only time that state citizenship could have also conferred national citizenship. Thereafter, only Congress could extend national citizenship to free blacks, but had never done so. States could not now confer U.S. citizenship, because the two were distinct, which reflected basic tenets of dual sovereignty.

Taney rejected the common law principle of birthright citizenship based on jus soli, that citizenship arose from where the person was born. This was not traditionally the only source of citizenship, the other being the jus sanguinis, by which citizenship arose through the parents’ citizenship, unless a person was an alien and became naturalized under federal law. Since blacks were not naturalized aliens, and their parental lineage could not confer citizenship on them under Taney’s reasoning, the rejection of citizenship derived from birth in the United States meant that even free blacks were merely subordinate American nationals owing obligations and allegiance to the United States but not enjoying the inherent political, legal, and civil rights of full citizenship. This was a novel status, but one that became significant several decades later when the United States acquired overseas dominions.

After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment was adopted. The very first sentence defines one basis of citizenship. National citizenship and state citizenship are divided, but the division is not identical to Taney’s version. To counter the Dred Scott Case and to affirm the citizenship of the newly-freed slaves, and, by extension, all blacks, national citizenship became rooted in jus soli. If one was born (or naturalized) in the United States and was subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, that is, one owed no loyalty to a foreign government, national citizenship applied. State citizenship was derivative of national citizenship, not independent of it, as Taney had held, and was based on domicile in that state.

The Chief Justice also rejected the idea that blacks were entitled to the same privileges and immunities of citizenship as whites. Although Taney viewed the Constitution’s privileges and immunities clause in Article IV broadly, if blacks were regarded as full state citizens under the Constitution, then Southern states could not enforce their laws that restricted the rights of blacks regarding free speech, assembly, and the keeping and bearing of arms. That, in turn, would threaten the social order and the stability of the slave system.

An expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Joerg W. Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at: http://www.tokenconservative.com/.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!