May 30, 1854: The Kansas-Nebraska Act is Signed, Disrupting Years of Sectional Compromise

The cascade of events leading to John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid, and 700,000 dead on countless Civil War battlefields, began with a cynical ploy by Illinois Senator Stephen Douglas to help land speculators and political donors.

America’s founding was an intricately crafted series of compromises and rules of engagement to balance regional interests. One of the fundamental points of conflict was slavery.

Slavery was integral to the economic vitality and culture of southern states. As America expanded westward, increasingly complex arrangements maintained the North/South regional political balance. Western settlers quickly became a third regional interest.

For decades, three titans of the U.S. Senate: Daniel Webster representing Northern interests, John C. Calhoun representing Southern interests, and Henry Clay representing the West debated and compromised to keep America united. Their agreements were tested as the Louisiana Purchase, and then the Mexican War, created vast land masses for settlement, economic development, and political power.

Slavery became the epicenter of regional rivalries. The South wanted to maintain parity in the Senate, balancing adding a new free state with a slave state. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850 maintained the political balance while avoiding confronting slavery. Most Americans, even Southerners, hated the institution. They hoped that slavery, if left alone, would somehow fade away over decades to come.

In the minority were Northern abolitionists, who wanted to end slavery in their lifetime. There were also Southern slavery advocates, who hoped to expand slavery westward and even southward by annexing Caribbean and Central American lands to bolster their power. The moderates held off both factions until the lure of land speculation, government contracts, and quick profits were added into the mix.

It began with the proposed trans-continental railroad to California. Southerners wanted the rail line to take a southern route. James Gadsden, President Franklin Pierce’s Ambassador to Mexico, negotiated the purchase of Mexican lands in what is now the southern border of Arizona and New Mexico on December 30, 1853 to assure sufficient railroad rights-of-way through less mountainous terrain.

The North wanted a northern route that began at St. Louis, Missouri and linked to Chicago, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and New York City. Most northern business leaders favored the northern route and felt that organization of the Nebraska Territory would facilitate this decision. However, rival business factions within Missouri wanted control of the route and the potential fortunes to be made from land speculation. Pro-slave forces threatened to block any efforts to organize Nebraska because Missouri would then be surrounded on its west, east, and north by free states.

Senator Stephen Douglas was a key architect of the Compromise of 1850 and Chairman of the Senate Committee on Territories. Douglas already had presidential aspirations, having lost the 1852 Democratic Party nomination to Franklin Pierce. He was preparing for another run in 1856. He wanted to help his Missouri-based political and financial allies, while avoiding a confrontation with Southerners. [1]

On January 4, 1854, Douglas introduced the Kansas-Nebraska Act. This act repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850. It opened the entire territory to popular or “squatter” sovereignty for determining whether the territories would be free or slave. At this time the Nebraska Territory encompassed the entire Louisiana Purchase from the Missouri Compromise line to the Canadian Border. Indiana Representative George Washington Julian, who would serve as the Chairman of the Committee on Organization for the 1856 Republican Convention, commented, “The whole question of slavery was thus re-opened.” [2]

The Congressional debate on the Kansas-Nebraska Act was tumultuous. Ohio Senator, Salmon Chase, published, “The Appeal of the Independent Democrats in Congress to the People of the United States,” in the New York Times on January 24, 1854. He declared the abandonment of the Missouri Compromise a “gross violation of a sacred pledge” and an “atrocious plot” to convert free territory into a “dreary region of despotism, inhabited by masters and slaves.” [3]

Northerners, and many Westerners, felt Southern politicians were dealing in bad faith. The “Nebraska Act” was viewed as a bold Southern power grab that threatened the nation’s future. Protests against the “Nebraska Act” spread throughout the North. Highly charged emotions fractured the Democratic Party, destroyed the Whig Party, and launched the Republican Party. Sixty-seven-years of America’s civic culture was falling apart.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act passed the Senate in March and the House of Representatives in early May. President Pierce signed the bill into law on May 30, 1854.

New York Senator William H. Seward responded to victorious Southern Senators by stating, “Since there is no escaping your challenge, I accept it in behalf of the cause of freedom. We will engage in a competition for the virgin soil of Kansas, and God give the victory to the side which is stronger in numbers as it is in right.” [4]

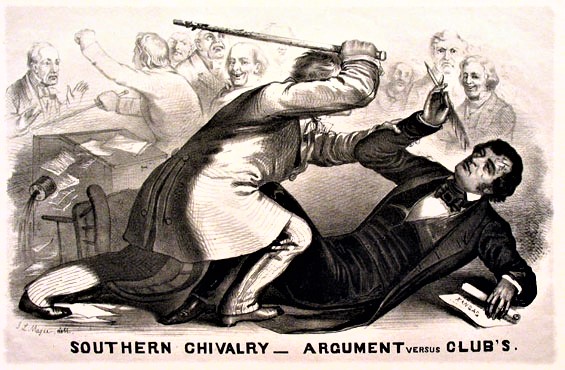

Both pro-slavery and anti-slave forces moved into the Kansas territory engaging in brutal guerilla warfare over the next five years. This sporadic civil war became known as “Bleeding Kansas.” It even spilled into the U.S. Senate Chamber. On May 22, 1856, South Carolina pro-slavery Democrat Representative Preston Brooks assaulted Massachusetts anti-slavery Republican Senator Charles Sumner in the Senate Chamber, bludgeoning him into unconsciousness. [5]

The regional civil war that erupted among Kansas settlers attracted the attention of John Brown, a key leader within the abolitionist movement. Wealthy and politically connected abolitionists funded and armed Brown, his many sons, and a growing number of paramilitary units, to enter the Kansas maelstrom.

Kansas became a killing ground, and a proving ground for Brown’s violent approach to ending slavery. The nation had embarked on a path leading to the most cataclysmic event in American history.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] Mayer, George H., The Republican Party 1854-1966 Second Edition (Oxford University Press, New York, 1966) page 25.

[2] Julian, George Washington, Political Recollections; Anthology – America; Great Crises in Our History Told by its Makers; Vol. VII (Veterans of Foreign Wars, Chicago, 1925) page 212.

[3] McPherson, James, Battle Cry of Freedom (Oxford University Press, New York, 1988) page 124.

[4] Ibid., page 145.

[5] Ibid., page 150.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!