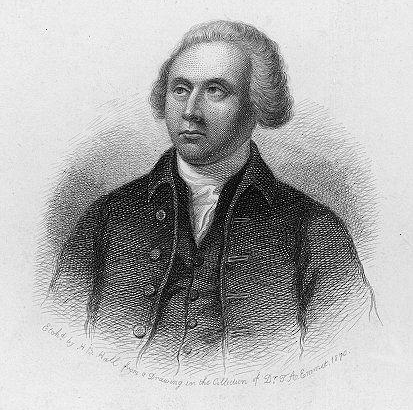

Thomas Nelson Jr. of Virginia gave his fortune and his health to further the cause of American Independence. When he and his fellow signers pledged “our lives, our fortunes and our sacred honor,” the men of the Second Continental Congress took that risk seriously. Some paid more than others and Thomas Nelson Jr. may have paid more than all of them. He was never a healthy man, but the mission of independence took much of the health that he did have, resulting in an early death at the age of 50. He also sacrificed his family’s fortune, spending and donating it to help win the War of Independence. This was truly a man who risked and gave all so that we could live in the nation that we do today.

Nelson was born in Yorktown, Virginia in 1738 to a very wealthy family. As many members of wealthy Virginia families were, Thomas was sent to England for his education. He graduated from Cambridge and returned to Virginia soon after. He married Lucy Grymes, a young widow who was a member of Virginia’s Randolph family, in 1762 and they had 13 children. The young family settled down as Nelson became a planter and an estate manager.

He was elected to Virginia’s House of Burgesses and was a very outspoken opponent of Britain and their policies toward the colonies and was one of the first leaders in the colonies to entertain the idea of an independency for the colonies. He believed that it was absurd to have the colonists hold an “affection for a people who are carrying on the most savage war against us.” On November 7, 1774, Nelson was a member of the Yorktown Tea Party. Citizens of York County, Virginia had passed a non-importation boycott in response to the Tea Act of 1773. When the British ship Virginia docked at Yorktown, enraged citizens marched onto the ship and dumped two imported half-chests of tea into the water.

Nelson was appointed as a member of the Second Continental Congress in mid-1775, replacing George Washington when Washington left the Congress to go to Boston to take command of the Continental Army. He had returned to Virginia and was in Williamsburg on May 15, 1776 when the Fifth Virginia Convention passed a series of resolutions declaring Virginia was no longer a part of the British Empire. Nelson immediately carried the news from Virginia to Philadelphia where Richard Henry Lee on June 6, 1776 made the official resolution for independence within the Second Continental Congress, that would lead to the Declaration of Independence. He eventually had to resign from the Congress due to poor health.

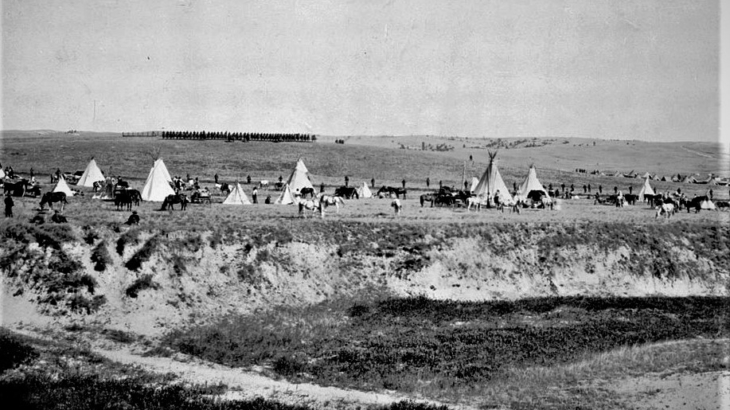

Nelson was later appointed a brigadier general in the Continental Army and commanded the Virginia militia during the battle of Yorktown in 1781 during the American Revolutionary War. It was here that one of the most selfless acts of his life took place as he ordered the artillery of the Continental Army to fire on his home, where several British officers were headquartered. The home was heavily damaged. The surrender of the British troops at Yorktown occurred soon after.

In June of 1781, Nelson became the second governor of Virginia, succeeding Thomas Jefferson. He had to resign in November of 1781 due to poor health. By this point in his life, he had lost almost everything. His businesses were destroyed. He was owed over two million dollars by the United States government for his loans to help finance the French fleet and their aid to the war effort. He was never repaid and his financial well-being was destroyed.

Nelson passed away at his home at the age of 50 in 1789 from severe asthma. His body was originally buried in an unmarked grave in Yorktown because of a fear that creditors may hold his body for collateral until his debts were paid. He now rests under a fitting stone that pays tribute to him and his service to the United States, including honoring his service as a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

Once, after the war, when he was asked if his treatment was worth it, Nelson replied that if he had to, he “would do it all over again.” After his countless sacrifices, Thomas Nelson Jr. still believed in his nation and his service to it.

Val Crofts serves as Chief Education and Programs Officer at the American Village in Montevallo, Alabama. Val previously taught high school U.S. History, U.S. Military History and AP U.S. Government for 19 years in Wisconsin, and was recipient of the DAR Outstanding U.S. History Teacher of the Year for the state of Wisconsin in 2019-20. Val also taught for the Wisconsin Virtual School as a social studies teacher for 9 years. He is also a proud member of the United States Semiquincentennial Commission (America 250), which is currently planning events to celebrate the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence.

Val Crofts serves as Chief Education and Programs Officer at the American Village in Montevallo, Alabama. Val previously taught high school U.S. History, U.S. Military History and AP U.S. Government for 19 years in Wisconsin, and was recipient of the DAR Outstanding U.S. History Teacher of the Year for the state of Wisconsin in 2019-20. Val also taught for the Wisconsin Virtual School as a social studies teacher for 9 years. He is also a proud member of the United States Semiquincentennial Commission (America 250), which is currently planning events to celebrate the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor