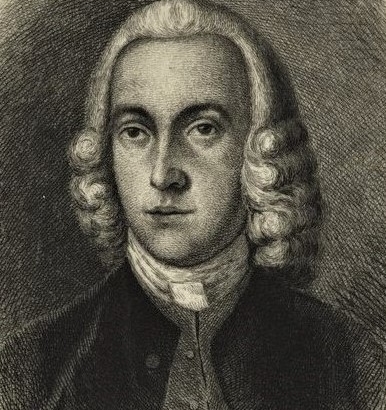

George Ross of Pennsylvania: Minister, Lawyer, Army Colonel, Continental Congress Delegate, Uncle of Betsy Ross, and Declaration of Independence Signer

Every American has heard the name Elizabeth Griscom, right? No? Perhaps you will recognize her by her married name: Elizabeth “Betsy” Ross, wife of John Ross. Ah, now we’re getting somewhere. Yes, Mrs. Ross was an accomplished seamstress and her particular work on a particular flag immortalized her name in American history. But Betsy also had a not-so-distant relative who should be just as famous, but is not. This relative is her uncle, George Ross, Jr. George Ross, Jr. signed an important American document in the summer of 1776.[i] It is to this “Colonel Ross” we turn today.

There were three sorts of delegates who attended the Continental Congress in the early to mid-summer of 1776. The first were those who took part in the debates over independence and were able to eventually sign the Declaration of Independence which resulted from those debates. The second were those who took part in the debates over independence and would not or never got to sign the declaration. The third were those who did not take part in the debates themselves but nevertheless had the opportunity to sign the final document. George Ross of Pennsylvania falls into the third category.

George Ross Jr. was born May 10, 1730, in Newcastle, Delaware, into a large family that could trace its lineage back to 1226 when Farquhar Ó Beólláin (1173-1251) was named the 1st Earl of Ross by King Alexander II of Scotland. Reverend George Ross Sr., with a fresh degree from Edinburgh, had arrived America in 1705[ii] as a missionary sent by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.[iii] He served first as rector for Immanuel Church in Newcastle, Delaware[iv] from 1705 until 1708 and then again from 1714 to 1754. Ross served in other area churches as well. At St. James’ Mill Creek Church in Wilmington, Delaware, he conducted their first service on July 4, 1717. Reverend Ross thought highly enough of learning to see that each of his sixteen children (by two successive wives) received a solid homeschool education. George Jr. reportedly became proficient in Latin and Greek.[v]

At age twenty, without attending college (that we can document), George Jr. was admitted to the Pennsylvania Bar after two years of study in his half-brother John’s law office, and soon set up his own practice in nearby Lancaster, Pennsylvania. At some point Ross took on a client, a young lady, named Ann Lawler. A romance soon blossomed and they were married August 14, 1751. Ann was reportedly a strikingly beautiful young woman, the only child of a prominent local family. Together, George and Ann produced two sons and a daughter. “Beauty was a word that defined Ann Lawler Ross and her children, in particular. Tradition states that prior to 1760 the artist Benjamin West came to make the portraits of the Ross family at their lovely country home in Lancaster… Mr. Flower, a friend of both George Ross and Benjamin West stated, ‘The wife of Mr. Ross [Ann] was greatly celebrated for her beauty and she had several children so remarkable in this respect as to be objects of general notice.’”[vi] George, Ann and their growing family attended St. James Episcopal Church in Lancaster,[vii] where George became a vestryman.[viii]

Ross’ skill as a lawyer was quickly noticed, resulting in his appointment as Crown Prosecutor (Attorney General) for Carlisle, Pennsylvania, serving for 12 years. In 1768, he was elected to the Pennsylvania legislature, representing Lancaster. There his Tory politics began to change and he was soon heard supporting the growing calls for American independence.

On May 30, 1773, Ann Ross died unexpectedly at age 42, and was buried at Saint James Church Cemetery in Lancaster.

The next year George was elected to the First Continental Congress, receiving one less vote than Benjamin Franklin himself.[ix] The Congress opened on September 5, 1774 in Philadelphia and was notable for producing a compact among the colonies to boycott British goods unless parliament rescinded the Intolerable Acts (which they did not). The Congress is also notable for producing the Declaration and Resolves[x] which laid out the grievances of the colonies. While at the Congress, Ross continued to serve as a member of Pennsylvania’s Committee of Safety.

“Both his own State Legislature and the National Council (i.e. the Continental Congress), made [Ross] a mediator in difficulties which arose with the Indians, and he acted the noble part of a pacificator, and a true philanthropist.”[xi]

The Second Continental Congress convened May 10, 1775, in response to the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord. A commission as a Colonel in the Continental Army was soon added to Ross’ resume although there is no indication he saw combat. The following year, on June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee of Virginia offered a resolution in the Congress declaring the colonies independent. In the debate which ensued, it quickly became apparent that some delegations needed time to communicate with their legislatures, so a vote on the measure was postponed until July 1. News that the resolution had been introduced spread quickly and Ross was noted to be “a warm supporter of the resolution of Mr. Lee.”[xii]

On July 15, 1776, the Pennsylvania Legislature appointed Benjamin Franklin and George Ross president and vice-president, respectively, of a convention to draft Pennsylvania’s first state constitution. The convention meeting “above stairs” in the State House (above the room Congress was using) adopted a new constitution for the state on September 28, 1776.

The journal of Congress for July 19, 1776 reports: “Resolved, That the Declaration passed on the 4th, be fairly engrossed on parchment, with the title and stile of “The unanimous declaration of the thirteen United States of America,” and that the same, when engrossed, be signed by every member of Congress.” It is this record which gives historians reason to claim that the Declaration was not signed on July 4, as was long the traditional narrative; the signing actually began much later after the engrossed copy was delivered.

There are 56 signatures on the engrossed copy of the Declaration. Eight men who had taken part in the July 4 vote to approve the Declaration never signed the document they debated.[xiii]

On July 20, Ross was appointed to replace either John Dickinson, Charles Humphreys or Thomas Willing (we are not sure which) as part of Pennsylvania’s delegation to the Congress.

John Dickinson presents an interesting case: Married to a Quaker, Dickinson strongly opposed going to war with Great Britain in order to obtain independence. When the July 1 vote took place – a non-binding, “test vote” in the Committee of the Whole – after an impassioned speech against the measure, Dickinson voted “No,” joining three other members of the Pennsylvania delegation in doing so. This made the delegation’s vote 4-3 against Lee’s resolution and a “No” vote was recorded for Pennsylvania (each colony got a single vote). Lee’s resolution passed, with nine of the thirteen colonies in favor, but the hoped-for unanimity had not materialized, as both Pennsylvania and South Carolina voted against it, New York’s delegation abstained since new instructions from their state had not yet arrived, and Delaware entered a null (split) vote as the votes of the two delegates who were present canceled each other. South Carolina requested the formal vote, as the Congress, be delayed to the following day, July 2.

On July 2, several “providential” events occurred. First, Caesar Rodney of Delaware walked in, still in his spurs. Rodney was a Delaware delegate, but was too sick to attend the Congress the previous day. Someone had ridden to his house the previous evening and informed him of Delaware’s split vote. Hearing this, Rodney had roused himself from his sickbed and ridden all night to Philadelphia. His vote in favor tipped the Delaware delegation’s vote to “Yes.” Over at the Pennsylvania table, there were two empty chairs where the day before had sat John Dickinson and Robert Morris, two of the previous day’s “No” votes. Without these two gentlemen present, Pennsylvania’s delegation vote changed from 4-3 against the measure to 3-2 in favor of the measure. South Carolina’s delegation had had an overnight change of heart and now voted in favor of the resolution. This left New York. Without new instructions (they did not arrive until July 19), New York had to once again abstain. This put the vote at twelve colonies in favor and one abstention. This was as close to the unanimity they were going to get that day, so President of Congress, John Hancock, declared the measure passed.

Dickinson promptly resigned his position in the Pennsylvania delegation, as did Humphreys and Willing. On July 20, George Ross joined the rest of the Pennsylvania delegation. Returning members were Dr. Benjamin Franklin, George Clymer, Robert Morris, Colonel James Wilson, John Morton, Dr. Benjamin Rush; and new members, Colonel James Smith, and George Taylor.

It was not unusual in that period for competent gentlemen to be given multiple, important responsibilities or postings. From July 20 to September 28, Franklin and Ross must have been quite the sight, walking upstairs and down, attending to their concurrent responsibilities in the Congress and the Pennsylvania Constitutional Convention. In addition to presiding as Vice-President, Ross also participated in drafting Pennsylvania’s Declaration of Rights.[xiv]

On August 2, George Ross joined the assembled delegates in adding his signature to the “Unanimous Declaration,” the last of the Pennsylvania delegation to do so.

The following year, 1777, Ross was reelected to the Continental Congress, but was forced to resign his seat before the session ended due to a recurrence of his chronic gout. The next year, he was elected Vice President of the Pennsylvania Assembly. In March of 1779, he was appointed a judge in the Pennsylvania Court of Admiralty, but four months later, on July 14, he died at the ripe young age of 49.[xv] He is buried in Philadelphia’s Christ Church Burial Ground.

The good citizens of Lancaster thought so highly of George Ross and his service to his country that they passed the following resolution:

“Resolved, that the sum of one hundred and fifty, pounds, out of the county stock, be forthwith transmitted to George Ross, one of the members of assembly for this county, and one of the delegates for this colony in the continental congress; and that he be requested to accept the same, as a testimony from this county, of their sense of his attendance on the public business, to his great private loss, and of their approbation of his conduct. Resolved, that if it be more agreeable, Mr. Ross purchase with part of the said money, a genteel piece of plate, ornamented as he thinks proper, to remain with him, as a testimony of the esteem this county has for him, by reason of his patriotic conduct, in the great struggle of American liberty.”[xvi]

Ross, however, declined this generous gift, stating to the committee which presented the resolution that his services to his country had been overrated, that he had been driven simply by his sense of duty, and that every man should contribute all his energy to promote the public welfare, without expecting pecuniary rewards.[xvii]

Visit Lancaster, Pennsylvania today and you will encounter George Ross Elementary School, Ross Street, and several historical markers commemorating “The Patriot George Ross.”

Many men seek greatness; a few of them find it. Some men have greatness thrust upon them. Other men quietly do their duty, to God and their country; George Ross was one of these men.

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the Constitution Leadership Initiative (CLI), a project to promote a better understanding of the U.S. Constitution by the American people. CLI provides seminars on the Constitution, including one for young people utilizing “Our Constitution Rocks” as the text. Gary presents talks on various Constitutional topics, writes periodic essays published on several different websites, and appears in period costume as James Madison, explaining to public and private school students “his” (i.e., Madison’s) role in the creation of the Bill of Rights and the Constitution. Gary can be reached at gary@constitutionleadership.org, on Facebook or Twitter (@constitutionled).

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

[i] Interestingly, George Ross’ sister, Gertrude, married George Read, who also went on to sign the Declaration.

[ii] https://www.immanuelonthegreen.org/.

[iii] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/United_Society_Partners_in_the_Gospel.

[iv] The church had been founded in 1689.

[v] J. B. Lossing, Signers of the Declaration of Independence, New York: Derby & Jackson, 1856, p. 130.

[vi] Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence – George Ross, accessed on 14 April 2021 at https://www.dsdi1776.com/signers-by-state/george-ross/.

[vii] St. James Episcopal Church of Lancaster was founded in 1744, also by a Church of England missionary.

[viii] https://www.hmdb.org/m.asp?m=5204.

[ix] https://lifewithldub.blogspot.com/2014/10/the-lancasters-hero-and-patriot-george.html.

[x] Read the Declaration at https://avalon.law.yale.edu/18th_century/resolves.asp.

[xi] Ibid p. 132.

[xii] Op cit.

[xiii] Those unable or unwilling to sign the Declaration were John Alsop, George Clinton, Robert R. Livingston and Henry Wisner of New York; John Dickinson, Charles Humphreys and Thomas Willing of Pennsylvania; and John Rogers of Maryland. All had left the Congress by August 2nd when the signing of the engrossed copy began.

[xiv] https://teachingamericanhistory.org/library/document/pennsylvania-declaration-of-rights-and-constitution/

[xv] One source sets Ross’ death in 1780 and the age of 50. See https://www.patriotacademy.com/george-ross-lives-fortunes-sacred-honor/.

[xvi] http://colonialhall.com/ross/ross.php.

[xvii] Robert R. Conrad, ed, Sanderson’s Biography of the Signers to the Declaration of Independence, Philadelphia, 1846. P.439

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!