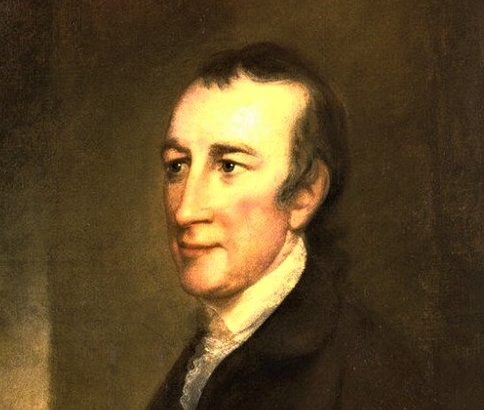

Thomas Stone of Maryland: Lawyer, Continental Congress Delegate, Committee of Correspondence Member, and Declaration of Independence Signer

Mary Land, the State of Maryland, was originally established in the early 17th century as a haven for Catholic immigrants to the American colonies. It was named after Henrietta Maria who was married to King Charles I, and was also a tribute to the Virgin Mary. But the American colonies were largely settled by Protestants with Puritans to the north, Anglicans to the South. Maryland, in spite of its Catholic heritage, tolerated religious diversity, so it was just a matter of time until Protestants dominated in Maryland. By the end of the 17th century, it had become largely inhabited by Protestants.

In 1688, the Glorious Revolution in England resulted in the Catholic King being replaced by Protestant monarchs. The proprietary Catholic colony in Maryland reverted to the British Crown.

In 1689, following the spirit of the Glorious Revolution in the mother country, Protestants in Maryland revolted and established a new Protestant government in the colony. Catholics were removed from office, prohibited from holding public office in the future, from practicing law, and from voting. Maryland’s citizens became loyal to the Crown over the next several generations before the onset of differences with the Crown in the 1760s.

Maryland’s principal cash crop was tobacco. Disputes among the growers in the colonies and the merchants in Britain who controlled the trade grew over time. After the French and Indian War, when Britain imposed taxes on the colonies to pay for Britain’s costs in prosecuting the war, additional disputes with Britain grew and a Sons of Liberty chapter was formed in Maryland.

Maryland citizens sympathetic to the patriot cause joined with other colonies in establishing Committees of Correspondence and its merchants joined with merchants in other colonies to boycott British imports. Sensing problems, Maryland’s Royal Governor prorogued the Colonial Assembly in the spring of 1774. Taking their cue from the Boston Tea Party, Maryland’s patriots held their own protests, the Chestertown Tea Party and the Annapolis Tea Party, against the British Tea Act.

A Provincial Convention was formed in Annapolis by the former members of the Colonial Assembly in 1774 and served as the patriots’ governing body until the signing of the Declaration of Independence. Delegates were sent to the First and Second Continental Congress. The Annapolis Convention, in January 1776, firmly instructed its delegates which included Thomas Stone, to attempt reconciliation with Britain and to not join in any attempt of the Continental Congress to declare the independence of the colonies. In spite of these instructions, Maryland already had its soldiers in the field with George Washington. Maryland’s soldiers became some of Washington’s most reliable Continentals after the “Maryland 400” held the line in Brooklyn allowing Washington and the remainder of his forces to escape annihilation by crossing the East River to Manhattan.

It was not until June 28, 1776 that Maryland’s Convention instructed its delegates to vote for Independence; this is the same day that Jefferson and the Committee of Five charged with drafting the document presented its draft of the Declaration of Independence to the Congress. Interestingly, not all delegates who voted for the Declaration on July 2 were official signatories. For example, John Rogers voted for independence on behalf of Maryland, but due to subsequent illness, was unable to sign the document.

Many delegates to the First and Second Continental Congresses considered themselves British citizens and sought reconciliation with Britain rather than revolution.

Thomas Stone was among those preferring reconciliation. He was born in Maryland in 1743 into a wealthy family which emphasized a classical education for Thomas who, like many other young men of the time, used their classical education as a springboard into the study of law.

In 1764, he entered the practice of law and spent the subsequent decade focused on serving his legal clients. Little is known about his life until his marriage in 1768 to seventeen-year-old Margaret Brown, daughter of a prominent and wealthy Maryland family. Thomas and Margaret purchased land on which to build their home and establish their family. The family owned slaves to work the large tobacco plantation established on the land and because Thomas was often absent riding the law circuit, his brother managed the plantation.

In 1774, Thomas was chosen to be on his county’s Committee of Correspondence, the vehicle through which patriots in the colonies communicated with each other. Think of the Committees of Correspondence as a Private Facebook Group of the 18th century – not providing instantaneous communication among the colonies, but enabling each of the colonies to coordinate their efforts to reconcile with the British Crown and simultaneously provide support to those colonies already engaged in conflict with the British military and blockades.

Stone is variously known as a “Reluctant Revolutionary,” a “Quiet Patriot,” and a “Moderate” who used his legal skills in the background rather than as a great orator, like Patrick Henry and John Adams, whose names are more recognizable as the movers and shakers of the Revolution.

He was then appointed to represent Maryland at the Second Continental Congress. Even after the battles at Lexington, Concord, and Boston, Stone and most members of the Continental Congress strove for reconciliation. Stone strongly supported the 1775 Olive Branch Petition, which King George refused to read and which was rejected by Parliament. Even after rejection of the Olive Branch Petition, as noted above, the Annapolis Convention in January 1776 instructed its delegates to the Continental Congress to vote against independence.

As the British Navy, with more than 30,000 troops aboard hundreds of ships, assembled in New York’s harbor to prepare to do battle with Washington’s troops, including the Maryland Line, on Long Island, reconciliation appeared hopeless and sentiment among the delegates to the Congress moved more towards independence. Virginia’s Richard Henry Lee introduced the independence resolution to the Congress in early June and Jefferson began writing the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Stone moved ever so slowly, but firmly, in favor of independence, and cast his Yea vote on July 2. He returned on August 2 to sign the Declaration.

The next year, after having been appointed to the committee to draft the Articles of Confederation, he declined reappointment to the Congress because of health problems his wife experienced due to complications from smallpox. He returned to Maryland and was appointed to the Maryland Senate, where he served for the rest of his life. Maryland’s commitment to the Confederation was weak, but Stone used his persuasive powers to support the Confederation, which Maryland ratified in February 1781, the last state to do so almost two years after the 12th state.

Stone was appointed to represent Maryland at the Constitutional Convention, but his wife died in June, 1787, causing him to decline appointment. He became deeply depressed upon the death of Margaret and died just four months later with a “broken heart” apparently being the cause. He and Margaret were buried on their plantation which is administered today by the National Park Service.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maryland_in_the_American_Revolution

Protestant Revolution (Maryland) – Wikipedia

https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdmanual/01glance/chron/html/chron17.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annapolis_Convention_(1774%E2%80%931776)

https://digital.lib.niu.edu/islandora/object/niu-amarch%3A103286

https://msa.maryland.gov/msa/mdstatehouse/html/independence.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Rogers_(Continental_Congress)

https://www.nps.gov/people/thomas-stone.htm

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Stone

https://www.thebaynet.com/articles/0616/the-quiet-patriot-thomas-stone-of-haberdeventure.html

http://colonialhall.com/stone/stone.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olive_Branch_Petition

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

My interest in the subject started with question I googled this morning of the name of the

Italian American signer of the Declaration of Independence of the United States. His last name is listed as Paca and I am sorry I didn’t make note of it being have made inquiry on my cell phone. But I must say it brought the American Revolution to life and tears to my eyes due to Pride in America during these troubled

Times and being born of Italian immigrants. I served in Army four years and made some minor contributions to the American way of life and always Proud to be an American. Thank you, N. Tullo