Principle of Natural Law as the Foundation for Constitutional Law

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

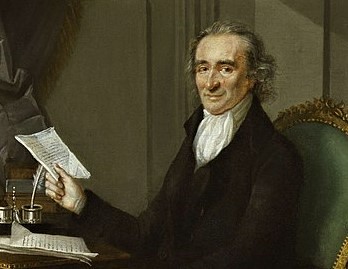

Thomas Paine became an immensely popular figure during the American War of Independence, primarily on the basis of his works Common Sense, a pamphlet initially published anonymously in 1776, and a series of pamphlets collectively referred to as The American Crisis, published from 1776 to 1783. They were ringing defenses of the American cause, well-written in uplifting and patriotic language easily accessible to ordinary readers.

Yet, only a handful of mourners attended that same Thomas Paine’s funeral three decades later, he having estranged many American leaders by his attacks on the character of George Washington in an open letter published in 1796. As well, his many occasions of writing negatively about organized religion, especially in the three parts of the pro-deism Age of Reason, had alienated much of the American public.

In between, Paine lived in England, where he soon became the target of official displeasure after publishing vigorously anti-monarchist and anti-aristocratic tracts in the two volumes of Rights of Man. While these works were widely read in England, his enthusiastic support of the French Revolution cost him popularity. Fearing prosecution, he fled to France.

Paine was initially very well received in the revolutionary French Republic. He was elected to the National Convention and appointed to its committee to draft a constitution. However, he soon made himself unpopular with the radical faction and eventually was imprisoned and slated for execution. He was saved from a date with the guillotine by the fall of the radical leader Maximilien Robespierre and subsequently was released from prison by the intervention of the new American ambassador, James Monroe.

He stayed a few more years and met Napoleon Bonaparte, who spoke admiringly about him, at least until Paine denounced the future emperor as a charlatan. Not long thereafter, Paine decamped for the United States at the invitation of one of his more steadfast friends, President Thomas Jefferson.

What raised Paine to such heights of fortune was his talent for “plain speaking.” That was also a cause for his lows, when his direct style rubbed influential persons the wrong way. His works during the Revolutionary Period were said to have made independence inevitable by bringing the common people to the cause, the people who might not have understood some of the more refined philosophical arguments made by elite American intellectuals citing elite European and ancient intellectuals. His most famous work, Common Sense, sold 500,000 copies by the end of the war in a country of fewer than 3 million free persons, including children. Jefferson, comparing him to Benjamin Franklin as an essayist, opined that, “No writer has exceeded Paine in ease and familiarity of style, in perspicuity of expression, happiness of elucidation, and in simple and unassuming language.”

The first installment of The American Crisis began with a stirring call to action for a demoralized American army: “These are the times that try men’s souls: The summer soldier and the sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of their country; but he that stands it now, deserves the love and thanks of man and woman. Tyranny, like Hell, is not easily conquered; yet we have this consolation with us, that the harder the conflict, the more glorious the triumph.” Four days after its publication in a Philadelphia newspaper, General George Washington had the pamphlet read to his soldiers recovering near the Delaware River after a long retreat from New York. The following night, Christmas Eve, the army crossed that river during a winter storm and, on Christmas Day, won a resounding victory at Trenton, New Jersey.

Paine’s value as a propagandist was not just in the cause of revolution and independence. He was a committed republican, to the point that it alienated some of his erstwhile admirers. The purpose of the quoted document, Dissertation on First Principles of Government, was to reiterate and develop the points about hereditary versus representative government made in Rights of Man. Having concluded that hereditary government was a form of tyranny, and even treason against successive generations, Paine rooted representative government in the inherent equality of human beings. The most significant right which flows from that equality is the right of property in oneself. If government is to be formed, as it must for the better protection of people in their persons and estates, each adult has the right to participate in that process on the principle of equality. If much of this sounds like the philosophy of John Locke, that should be no surprise, in light of the popularity of Lockean ideas at that time. But Paine made those ideas more accessible to ordinary people. Unlike many American state constitutions at the time, Paine rejected property qualification for voting. He did not address female suffrage, although his frequent reference to “man,” if used generically, did not foreclose that possibility.

In the minds of many 18th-century writers on politics, the problem of a general franchise and a purely elective government was the danger it posed of degenerating into a democracy. Paine did not reject such a democracy outright, although he considered it impractical for large political entities such as France and the United States. Those parts of the Dissertation could have fit comfortably in The Federalist. Others, such as the paragraphs addressing the nature of executive power and its formulation in the Constitution of 1787, sat less well.

Paine’s discussion of the importance of voting was consistent with classical American republicanism, which also considered the “republican principle” of the vote as the mainstay of liberty. As a matter of practical application, Paine emphasized the use of majority rule, whether exercised through direct democracy in a town or a representative body. As he wrote in the Dissertation, “In all matters of opinion, the social compact, or the principle by which society is held together, requires that the majority of opinions becomes the rule for the whole and that the minority yields practical obedience thereto.”

Paine was not nearly as agitated about the baleful influence of factions as James Madison was in The Federalist. That noted, Paine’s solution to the potential problem of majority dominance over a political minority was similar to Madison’s explanation in No. 10 of The Federalist about the relative lack of danger from an entrenched majority faction in Congress compared to town or state governments. Paine observed that political majorities change depending on the issues involved, so there is constant rearranging of the composition of whatever constitutes a majority. “He may happen to be in a majority upon some questions, and in a minority upon others, and by the same rule that he expects obedience in the one case, he must yield it in the other.” Like Madison at that time, Paine could not know about the subsequent emergence of organized political parties and party discipline over elected officials.

There is, however, a danger from straight majority rule, whether that rule is exercised through direct voting by whatever class of persons is qualified to vote or in a legislature composed of some class of persons deemed qualified to stand for public office and represent the people. No matter how many laudatory words 18th-century American republicans might put forth about voting and representation, consent of the governed, and majority rule, the temptation to vote for self-interest rather than the res publica, the general wellbeing of society, and to call forth the “spirit of party,” becomes irresistible. As has been noted by cynics, without additional protections “Democracy is two wolves and a lamb deciding what is for dinner.” Or, as the 19th-century New York lawyer and judge Gideon Tucker quipped, “No man’s life, liberty, or property are safe while the legislature is in session.” Jefferson commenting in Notes on the State of Virginia on the structure of the Virginia Constitution of 1776, insisted “An elective despotism was not the government we fought for.” One of the great fallacies of modern political discourse is that we just need to get more people to vote to bring about a just society and to protect personal liberty.

Paine recognized the danger of party spirit and the need for a constitution to restrain the excesses of government, including of government by popular mandate. He decried the brutality of the French Revolution and noted, “[I]t is the nature and intention of a constitution to prevent governing by party, by establishing a common principle that shall limit and control the power and impulse of party, and that says to all parties, THUS FAR SHALT THOU GO AND NO FARTHER.” [All emphases in the original.] In addressing “party,” Paine was referring to self-interest, in this context the interest to gain and exercise unrestricted power. He opined that, “[h]ad a constitution been established [in 1793] … the violences that have since desolated France, and injured the character of the revolution, would … have been prevented.”

Instead, “a revolutionary government, a thing without either principle or authority, was substituted in its place; virtue and crime depended upon accident; and that which was patriotism one day became treason the next.” Lacking a constitution that protects inherent rights causes an “avidity to punish, [which] is always dangerous to liberty. It leads men to stretch, to misinterpret, and to misapply even the best of laws. He that would make his own liberty secure must guard even his enemy from oppression; for if he violates this duty, he establishes a precedent that will reach to himself.”

Paine’s insistence on a constitution as a check on government focused on the need for the type of protections found in the American system mainly in the Bill of Rights. A declaration of rights had to be more than a collection of meaningless slogans. It had to limit governmental action directly and expressly. Moreover, such limits were not a matter of political grace. “An enquiry into the origin of rights will demonstrate to us the rights are not gifts from one man to another, not from one class of men to another; for who is he who could be the first giver? Or by what principle, or on what authority, could he possess the right of giving? A declaration of rights is not a creation of them, nor a donation of them. It is a manifest of the principle by which they exist, followed by a detail of what the rights are; for every civil right has a natural right for its foundation, and it includes the principle of a reciprocal guarantee of those rights from man to man.” The Constitution likewise enumerates certain rights but expressly does not purport to provide an exhaustive list. As the Ninth Amendment declares, there are other rights retained by the people. It is disheartening to hear so often from law students that the Constitution “grants us rights,” an understanding of the nature of rights at odds with that of the people who drafted and adopted the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution, and the Bill of Rights.

In the American system, the Constitution is not merely a collection of customs and traditions of political practice. It is a legal charter and has the essence of law enforceable, within limits, in courts of law. It is higher law in the sense that, in case of conflict between it and ordinary federal or state statutes, the Constitution prevails. But it addresses expressly only limited topics. Almost since the Constitution’s adoption, there has been debate about the authority of courts to look to other forms of higher law reflective of the principle of inherent rights to limit legislative authority, such as theories of natural law or natural rights. That debate continues, often in trying to define what the ambiguous term “liberty” means in the Constitution, for example, in relation to abortion, marriage, or gun ownership.

Another unresolved question is whether such higher law is superior to the Constitution itself. After all, the Constitution can be amended with the requisite supermajority votes prescribed in Article V of that charter. Suppose that a constitutional amendment were adopted that protected infanticide or that repealed the prohibition of slavery. Would infanticide or slavery, at that point constitutionally permissible, yet be consistent with natural law or natural rights? If the answer is “no,” it shows a recognition that certain rights inhere in each person as a matter of essence, not as a grant from a legislative majority or a constitutional supermajority. The religious skeptic in Paine might not allow him to go as clearly to the source of those rights as did the language of the Declaration of Independence that we are endowed with them by our Creator, but Paine would readily acknowledge the existence of such higher law.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!