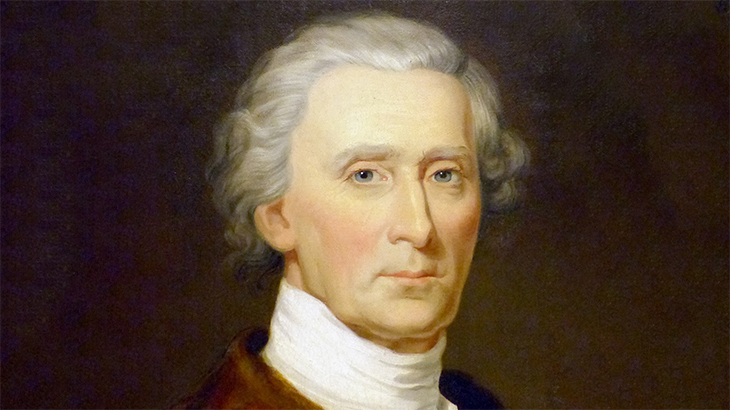

Charles Carroll of Carrollton was a third generation American. His grandfather emigrated from Great Britain to America in the late seventeenth century, procuring a large tract of land in Maryland. At ten Charles was sent to a Jesuit school, subsequently attending Jesuit colleges in French Flanders and Reims, and then attending the College Louis le Grand in Paris. The next few years he studied law in France and then in England, at the Temple, London.

Charles Carroll was impeccably educated in the classics. He spoke five languages and, according to Tocqueville, personified the “European gentleman.” In 1764, with his education completed, he crossed the Atlantic and returned to his native Maryland. In 1768, he married Mary Darnall, with whom he had seven children, three of whom survived beyond childhood.

Charles Carroll was a member of the Continental Congress, a framer of the Maryland Constitution of 1776, a member of the Maryland legislature, and a member of the U.S. Senate. The respect he earned among his peers was not easily obtained, for Carroll was of Irish descent (originally of County Offaly, between Dublin and Galway), and a Catholic – or Papist, as Roman Catholics were often then called – the pariah of 18th century Anglo-American Protestant society. Even in his home state of Maryland, which had the largest concentration of Roman Catholics of any of the states, Catholics were denied the right to vote and to hold office. Carroll set about to change that, penning the “First Citizen” letters, ultimately succeeding in placing a provision in the Maryland Constitution of 1776 guaranteeing all Christians (i.e., including Catholics) the right to participate in public life.

The years leading up to the American Revolution were for Carroll a time of intense public spiritedness in defense of the rights and liberties of the colonists. Among many posts of leadership, Carroll was a member of a Committee of Correspondence, of the Maryland Convention of 1775, and of the delegation to Canada (with Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Chase) seeking Canadian support for the American war for independence. Like many others, Carroll pronounced the doctrine of no taxation without representation, and he prodded and provoked, persuaded and led his fellow Marylanders to join the cause of independence.

Elected delegate to the Continental Congress on July 4, 1776, Carroll took his seat on the 18th and signed the Declaration of Independence on August 2nd, when the engrossed parchment copy was presented for signature.

After the war, the implementation of the Articles of Confederation, and finally the establishment of the new Constitution, Carroll became a Senator in the first Congress of the United States. Supportive of Alexander Hamilton’s national and financial program (and opposed to the Republican financial and foreign policy agenda), Carroll became a member of the Federalist Party, helping broker deals such as placing the temporary capital in Philadelphia and the permanent one on the Potomac, and adjusting land claims between Virginia and his home state of Maryland.

One of the wealthiest families in America at the time of the founding – some would say the wealthiest, with an estate estimated at over 2 million pounds sterling at that time – Charles Carroll was in a position to contribute substantially to the financing of the war. At the same time, he did not take his good fortune for granted. In the old world, the family has been systematically stripped of their holdings by hostile Protestant Englishmen. In the new world, the security of property, freedom of religion, and equal treatment before the law was a work in progress. Writing to James Warren in 1776, John Adams noted that Charles Carroll “continues to hazard his all: his immense Fortune, the largest in America, and his Life. This Gentlemans Character, If I foresee aright” Adams remarked, “will hereafter make a greater Figure in America.”

Charles Carroll inherited a ten-thousand-acre plantation from his father, and with that estate, hundreds of slaves. He was a slaveholder; he was also an abolitionist. He worked for the gradual abolition of slavery, sponsoring a bill in the Maryland legislature that required all slave girls to be educated and then at 28 years old set free, that they may in turn educate their husbands and children.

Charles Carroll was the last surviving signer of the American Declaration of Independence, called by one contemporary “the last of the Romans.” Of the principles of the Declaration, he said, “I do hereby recommend [them]to the present and future generations…as the best earthly inheritance their ancestors could bequeath to them.”

While the name Carroll may not be as renown as Washington, Jefferson, Adams, or Franklin, or as familiar as Kennedy or Reagan, and though there be no cities, states, rivers or colleges that serve as eternal reminders of his deeds and sacrifices, that does not make us any the less in his debt.

Indeed, if some Americans look to the presidential election of John F. Kennedy as the moment that marked the acceptance of Irish Catholics in the Anglo-Protestant dominated political mainstream of 20th century America, the possible pathway for an Irish Catholic president in America was originally paved by the Carroll family, particularly Charles Carroll and his cousin Daniel, a signer of the U.S. Constitution.

The war for independence and the founding of the United States was a work that could only have been accomplished by the dedicated work of many minds and many hands. Charles Carroll was one of the men who made this land we call America and who left to us the earthly inheritance – and the ongoing work – of keeping alive the principles of ’76.

Colleen A. Sheehan is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies with the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership of Arizona State University.

Colleen A. Sheehan is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies with the School of Civic and Economic Thought and Leadership of Arizona State University.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor