Half-Slave and Half-Free? The Injustice of the Dred Scott Decision

In the 1850s, the United States was deeply divided over the issue of slavery and its expansion into the West. Northerners and southerners had been arguing over the expansion of slavery into the western territories for decades. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had divided the Louisiana Territory at 36’30° with new states north of the line free states and south of the lines slave states. The delicate compromise held until the Mexican War.

The territory acquired in the Mexican War of 1846 triggered the sectional debate again. In 1850, Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky engineered the Compromise of 1850 to settle the dispute with the help of Stephen Douglas. But, in 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act permitted settlers to decide whether the states would be free or slave according to the principle of “popular sovereignty.” Pro and anti-slavery settlers rushed to Kansas and violence and murder erupted in “Bleeding Kansas.” Meanwhile, southerners spoke of secession and observers warned of civil war.

The United States faced this combustible situation when Chief Justice Roger B. Taney sat down in late February 1857 to write the infamous opinion in the case of Dred Scott v. Sandford that would go down as a travesty of constitutional interpretation and one of the greatest injustices by the Supreme Court.

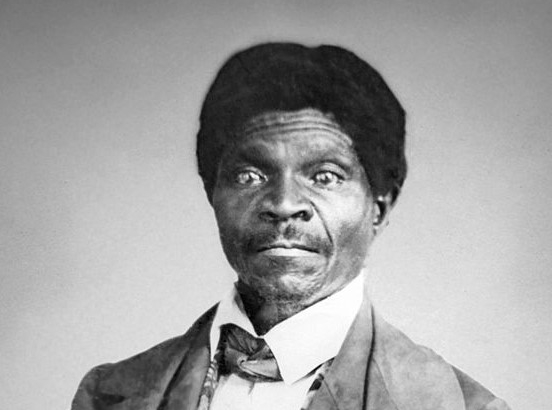

Dred Scott was a slave who had been owned by different masters in the slave states of Virginia and Missouri. Dr. John Emerson was an Army surgeon who was one of those owners and brought Scott to the free state of Illinois for three years and then the free Wisconsin Territory. Scott even married another slave while on free soil. Emerson moved back to Missouri and brought his enslaved with him just before he died. Scott sued Emerson’s widow for his freedom because he had lived in Illinois and Wisconsin, where slavery was prohibited.

Southern and Northern state laws and courts had long recognized the “right of transit” for slaveowners to bring their slaves while briefly traveling through free states/territories or remaining for short durations. However, they also recognized that residence in a free state or territory established freedom for slaves who moved there. In fact, Missouri’s long-standing judicial rule was “once free, always free.” Many former slaves who returned to Missouri after living in a free state or territory had successfully sued in Missouri courts to establish their freedom. The Dred Scott case made its way through the Missouri and federal courts, and finally reached the Supreme Court.

The attorneys presented oral arguments to Taney and the other justices in February 1856. The justices met in chambers but simply could not come to a consensus. They asked the lawyers to re-argue the case the following December, which coincidentally delayed the decision until after the contentious presidential election that allowed the Court to maintain the semblance of neutrality. But, Justice Taney sought to remove the issue from the messy arena of democratic politics and settle the sectional dispute over slavery in the Court.

After hearing the case argued for a second time, the justices met in mid-February 1857 to consider the case. They almost agreed to a narrow legal opinion that addressed Dred Scott’s status as a slave in a free state. However, they selected Chief Justice Taney to write the opinion. He used the opportunity to write an expansive opinion that would avert possible civil war.

On the morning of March 6, Taney read the shocking opinion to the Court for nearly two hours. Taney, speaking for seven members of the Court, declared that all African-Americans—slave or free—were not U.S. citizens at the time of the founding and could not become citizens. He asserted that the founders thought that blacks were an inferior class of humans and “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect,” and no right to sue in federal court. This was not only a misreading of the history of the American founding but a gross act of injustice toward African Americans. Taney could have stopped there, but he believed this decision could end the sectional conflict over the expansion of slavery. He declared that the Missouri Compromise was unconstitutional because Congress had no power to regulate slavery in the territories despite Article IV, section 3 giving Congress the “power to dispose of and make all needful rules and regulations respecting the territory or other property belonging to the United States.” According to his reasoning, slavery could become legal throughout the nation. Finally, Taney pronounced that Dred Scott, despite his residence in the free state and territory that allowed other slaves to claim their freedom, was still a slave.

The Dred Scott decision was not unanimous; Justices Benjamin Curtis and John McLean wrote dissenting opinions. Curtis’s painstakingly detailed research in U.S. history demonstrated that Taney was wrong on several points. First, Curtis convincingly showed that free African-Americans had been citizens and even voters in several states at the time of the founding. He wrote that slavery was fundamentally “contrary to natural right.” Furthermore, Curtis pointed out that by settled practice and the Constitution, Congress did indeed have power to legislate regarding slavery. He provided evidence that Congress had legislated with respect to slavery more than a dozen times before the 1820 Missouri Compromise.

The Dred Scott decision was supposed to calm sectional tensions in the United States, but it worsened them. Northerners expressed great moral outrage, and southerners doubled down on the Court’s decision that African Americans had no rights and Congress could not regulate slavery’s expansion. Indeed, the Court’s decision greatly exacerbated tensions and contributed directly to events leading to the Civil War. Instead of leaving the issue to the people’s representatives who had successfully negotiated important compromises in Congress to preserve the Union, Taney and other justices arrogantly thought they could settle the issue.

Taney’s understanding of American republican government was that only the white race enjoyed natural rights and consensual self-government. Abraham Lincoln continually attacked the decision in his speeches and debates. Lincoln stood for a Union rooted upon natural rights for all humans. He did not believe that the country could survive indefinitely “half slave, half free.” He argued that the Declaration of Independence “set up a standard maxim for free society” of self-governing individuals. Lincoln also opposed the Dred Scott decision because of its impact on democracy. If the Court’s majority gained the final say on political decisions, Lincoln thought “the people will have ceased to be their own rulers.”

The different views of slavery, its expansion, and the principles of republican self-government were at the core of the Civil War that ensued three years later. During the war, President Lincoln freed the slaves in Confederate states with the Emancipation Proclamation and laid down the moral vision of the American republic in the Gettysburg Address. He wrote: “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” The bloody Civil War was fought so that “this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. He is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

Hey I’m Interested in Books on DRED SCOTT* Thxu’ Enjoy Peace.