Founding Fathers on Designing a Constitution for Serving the American People, Not a Government of Machiavellian Authority

In Federalist 31, using references to math and science, Hamilton says that, “IN DISQUISITIONS of every kind, there are certain primary truths, or first principles, upon which all subsequent reasonings must depend. But in the sciences of morals and politics, men are found far less tractable; yielding to some untoward bias, they entangle themselves in words and confound themselves in subtleties. Strong interests, passions, and prejudices may degenerate into obstinacy, perverseness, or disingenuity.”

In Federalist 37, Madison says, “In some, it has been too evident from their own publications, that they have scanned the proposed Constitution, not only with a predisposition to censure, but with a predetermination to condemn.” On the other hand, (The Federalist Papers) “solicit the attention of those only, who add to a sincere zeal for the happiness of their country, a temper favorable to a just estimate of the means of promoting it. A faultless plan was not to be expected. The most that the convention could do in such a situation, was to avoid the errors suggested by the past experience of other countries, as well as of our own; and to provide a convenient mode of rectifying their own errors, as future experiences may unfold them.”

Madison notes that the delegates to the Constitutional Convention sought to find the best combination of features in the construction of government that would provide “stability and energy in government with inviolable attention due to liberty and to the republican form. They sought to avoid those features that they believed would risk the destruction of their proposed government as quickly as was that of the Republican government of Florence in the early 16th century.

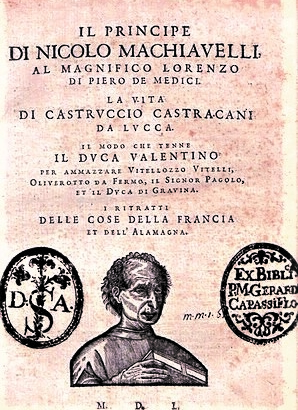

In the turmoil of Florentine politics, Machiavelli believed that Republican government was necessary for good government, but that many who sought to be autocratic rulers had different ideas of what good government looked like. Machiavelli observed that those opposed to good government under a Republican form believed (1) that moral and spiritual virtues are not essential for the administration of government and must be avoided by ensuring that government is secular; (2) that Christianity, in particular, is destructive to governing; (3) that fear and the threat of coercive force are more important than legal force; (4) that a forceful, and even violent, response is the only appropriate means to prevent enemies of the state from upsetting the political order of the state; (5) that what’s good for the state should guide government rather than what’s good for its individual citizens; (6) that the head of state must use whatever means is at his disposal to do whatever is necessary to maintain control and power; (7) that, to ensure peace and tranquility in the country, a consequence is that citizens will be disarmed.

It’s not difficult to understand Machiavelli’s observations when one considers the period in which he was an official in Florence’s government. Although a Republic existed after the Medici government was overthrown, it lasted less than 20 years; in addition, a co-conspirator in the overthrow of the Republic was the Papal forces. Thus, he seems to have concluded that Christian leaders may have been no more moral than secular leaders and that Christian leaders were as willing as secular leaders to exercise force to gain control of government and the populace.

America’s Founding Fathers, all of whom had studied the Bible as an essential part of the classical education, believed that moral and spiritual virtues were necessary for good men to establish good government. They believed that the government should be entrusted with limited powers, with those powers determined by the people through their elected representatives, rather than with unelected governors who used force to obtain security for the people, but at the expense of the people’s liberty. And they believed that government existed to secure the rights of the people rather than to ensure the long-term viability of the state.

As they debated the construction of a new Republican form of government in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787, they sought to use their knowledge of republican and authoritarian governments over thousands of years to construct one that might prevent their proposed republic from ultimately being overcome by authoritarian-minded opponents. The features of acquiring authoritarian power in government noted by Machiavelli were features that the Convention delegates sought to minimize in their new Constitution.

Their Christian education and study of Aristotle’s Ethics informed them that leaders of good character were necessary for good government. John Adams, in a speech to the Massachusetts militia in 1798, said that “Our constitution was made only for a moral and religious people,” and George Washington reflected a similar sentiment when he said, in his Farewell Address, “Of all the dispositions and habits which lead to political prosperity, religion and morality are indispensable supports. . . And let us with caution indulge the supposition that morality can be maintained without religion.”

Yet they also recognized that no particular religion should require support by the citizens of the nation and that no religious affiliation should be required to hold federal public office. At the time, many of the 13 states had state-sponsored religions and, at a minimum, required that those citizens eligible for public office must be Protestants. In Article VI, Clause 3, of the United States Constitution, the Constitution clearly stated that, “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.” So, good character, moral, and ethical principles, generally acquired from education in religious and philosophical principles, were recognized as important for helping citizens acquire responsible civic virtue that the Founders considered necessary for good government of the people.

In crafting the Second Amendment, the Founders recognized that citizens who were disarmed would be unable to retain their liberty should authoritarian politicians attempt to seize power in the federal government.

Rather than adopting Machiavelli’s concept that government existed for the “good of the state,” the Founders decided that government existed to secure liberty for the people. The Constitution was designed to provide the government’s structure in support of the principles of the Declaration of Independence, most specifically the Declaration’s statement that, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.–That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.” To more forcefully communicate that government existed to secure the rights of the people, Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution specifies limited powers of the federal government and the Ninth Amendment states that, “The enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

Additional measures in the Constitution provided for two houses in Congress, one to represent the people and the other to represent the individual states. The President was given power to veto laws passed by both houses of Congress to prevent the legislature from accruing excessive power, and the Congress was given the power to override a Presidential veto to prevent a President from accruing excessive power. The Supreme Court was given the power to ensure that laws passed by Congress and signed by the President were in accord with the Constitution to prevent a situation in which both houses of Congress as well as the office of President were occupied by politicians of one faction and attempted to enact legislation to benefit their faction, in conflict with the Constitution.

If all else fails, then Article I of the Constitution provides for impeachment of the President, Vice President and all civil Officers for treason, bribery, or other high crimes and misdemeanors, with the additional check and balance providing that the House has the sole power to impeach and the Senate has the sole power to try all impeachments.

As noted above in Federalist 37, “A faultless plan was not to be expected.” The Founders attempted, to the best of their abilities, to construct a Constitution that reflected the strengths and minimized the weaknesses of republican governments over thousands of years of history, a history they knew well because of their classical education. Yet, they recognized that their conception of a federal government structure was an experiment, as reflected in what Benjamin Franklin said in his final speech at the Convention, “when you assemble a number of men to have the advantage of their joint wisdom, you inevitably assemble with those men, all their prejudices, their passions, their errors of opinion, their local interests, and their selfish views.” Later, when he was asked by a group of citizens what sort of government the delegates had created, his answer was, “A republic, if you can keep it.”

We’ve kept it for more than 230 years, overcoming many challenges to its existence. In his Gettysburg Address, President Lincoln reminded us that, “It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.” And President Reagan said in his 1964 speech, “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction. We didn’t pass it to our children in the bloodstream. It must be fought for, protected and handed on for them to do the same.” It’s up to us, we the people, not the government, to keep it going for another 230 years.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Prince#/media/File:Machiavelli_Principe_Cover_Page.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Prince#/media/File:Machiavelli_Principe_Cover_Page.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!