Guest Essayist: James C. Clinger

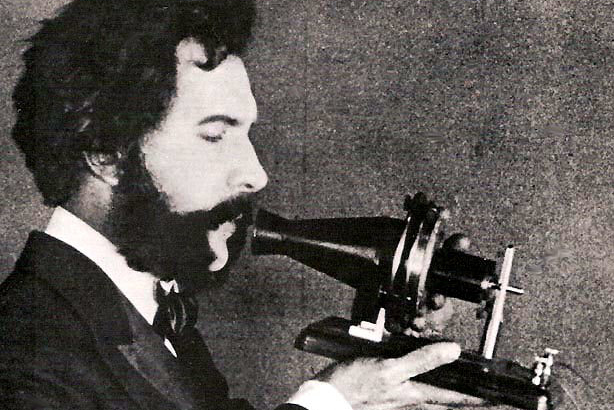

An admirer of inventors Bell, Edison, and Einstein’s theories, scientist and inventor Philo T. Farnsworth designed the first electric television based on an idea he sketched in a high school chemistry class. He studied and learned some success was gained with transmitting and projecting images. While plowing fields, Farnsworth realized television could become a system of horizontal lines, breaking up images, but forming an electronic picture of solid images. Despite attempts by competitors to impede Farnsworth’s original inventions, in 1928, Farnsworth presented his idea for a television to reporters in Hollywood, launching him into more successful efforts that would revolutionize moving pictures.

On September 3, 1928, Philo Farnsworth, a twenty-two year old inventor with virtually no formal credentials as a scientist, demonstrated his wholly electronic television system to reporters in California. A few years later, a much improved television system was demonstrated to larger crowds of onlookers at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, proving to the world that this new medium could broadcast news, entertainment, and educational content across the nation.

Farnsworth had come far from his boyhood roots in northern Utah and southern Idaho. He was born in a log cabin lacking indoor plumbing or electrical power. His family moved to a farm outside of Rigby, Idaho, when Farnsworth was a young boy. For the first time, Farnsworth could examine electrical appliances and electric generators in action. He quickly learned to take electrical gadgets apart and put them back together again, often making adaptations to improve their function. He also watched each time the family’s generator was repaired. Soon, still a young boy, he could do those repairs himself. Farnsworth was a voracious reader of science books and magazines, but also devoured what is now termed science fiction, although that term was not in use during his youth. He became a skilled violinist, possibly because of the example of his idol, Albert Einstein, who also played the instrument.[1]

Farnsworth excelled in his classes in school, particularly in mathematics and other sciences, but he did present his teachers and school administrators with a bit of a problem when he repeatedly appealed to take classes intended for much older students. According to school rules, only high school juniors and seniors were supposed to enroll in the advanced classes, but Farnsworth determined to find courses that would challenge him intellectually. The school resisted his entreaties, but one chemistry teacher, Justin Tolman, agreed to tutor Philo and give him extra assignments both before and after school.

One day, Farnsworth presented a visual demonstration of an idea that he had for transmitting visual images across space. He later claimed that he had come up with the basic idea for this process one year earlier, when he was only fourteen. As he was plowing a field on his family farm, Philo had seen a series of straight rows of plowed ground. Farnsworth thought it might be possible to represent visual images by breaking up the entire image into a sequence of lines of various shades of light and dark images. The images could be projected electronically and re-assembled as pictures made up of a collection of lines, placed one on top of another. Farnsworth believed that this could be accomplished based on his understanding of Einstein’s path-breaking work on the “photoelectric effect” which had discovered that a particle of light, called a photon, that hit a metal plate would displace electrons with some residual energy transferred to a free-roaming negative charge, called a photoelectron.[2] Farnsworth had developed a conceptual model of a device that he called an “image dissector” that could break the images apart and transmit them for reassembly at a receiver. He had no means of creating this device with the resources he had at hand, but he did develop a model representation of the device, along with mathematical equations to convey the causal mechanisms. He presented all of this on the blackboard of a classroom in the high school in Rigby. Tolman was stunned by the intellectual prowess of the fifteen year old standing in front of him. He thought Farnsworth’s model might actually work, and he copied down some of the drawings from the blackboard onto a piece of paper, which he kept for years.[3] It is fortunate for Farnsworth that Tolman held on to those pieces of paper.

Farnsworth was accepted into the United States Naval Academy but very soon was granted an honorable discharge under a provision permitting new midshipman to leave the university and the service to care for their families after the death of a parent. Farnsworth’s father had died the previous year, and Farnsworth returned to Utah, where his family had relocated after the sale of the farm. Farnsworth enrolled at Brigham Young University but worked at various jobs to support himself, his mother, and his younger siblings. As he had in high school, Farnsworth asked to be allowed to register in advanced classes rather than take only freshman level course work. He quickly earned a technical certificate but no baccalaureate degree. While in Utah, Farnsworth met, courted and eventually married his wife, “Pem,” who would later help in his lab creating and building instruments. One of her brothers would also provide lab assistance. One of Farnsworth’s job during his time in Utah was with the local Community Chest. There he met George Everson and Leslie Gorrell, who were regional Community Chest administrators who were experienced in money-raising. Farnsworth explained his idea to them about electronic television, which he had never before done to anyone except his father, now deceased, and his high school teacher, Justin Tolman. Everson and Gorrell were impressed with Farnsworth’s idea, although they barely understood most of the science behind it. Everson and Gorrell invited Farnsworth to travel with them to California to discuss his research with scientists from the California Institute of Technology (a.k.a., Cal Tech). Farnsworth agree to do so, and made the trek to Los Angeles to meet first with scientists and then with bankers to solicit funds to support his research. When discussing his proposed electronic television model, Farnsworth became transformed from a shy, socially awkward, somewhat tongue-tied young man to a confident and articulate advocate of his project. He was able to explain the broad outline of his research program in terms that lay people could understand. He convinced Gorrell and Everson to put up some money and a few years later got several thousand more dollars from a California bank.[4]

Philo and Pem Farnsworth re-located first to Los Angeles and then to San Francisco to establish a laboratory. Farnsworth believed that his work would progress more quickly if he were close to a number of other working scientists and technical experts at Cal Tech and other universities. Farnsworth also wanted to be near to those in the motion picture industry who had technical expertise. With a little start-up capital, Farnsworth and a few other backers incorporated their business, although Farnsworth did not create a publicly traded corporation until several years later. At the age of twenty-one, in 1927, Farnsworth filed the first two of his many patent applications. Those two patents were approved by the patent office in 1930. By the end of his life he had three hundred patents, most of which dealt with television or radio components. As of 1938, three-fourths of all patents dealing with television were by Farnsworth.[5]

When Farnsworth began his work in California, he and his wife and brother-in-law had to create many of the basic components for his television system. There was very little that they could simply buy off-the-shelf at any sort of store that they could simply assemble into the device Farnsworth had in mind. So much of their time was devoted to soldering wires and creating vacuum tubes, as well as testing materials to determine which performed best. After a while, Farnsworth hired some assistants, many of them graduate students at Cal Tech or Stanford. One of his assistants, Russell Varian, would later make a name for himself as a physicist in his own right and would become one of the founders of Silicon Valley. Farnsworth’s lab also had many visitors, including Hollywood celebrities such as Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford, as well as a number of scientists and engineers. One visitor was Vladimir Zworykin, a Russian émigré with a PhD in electrical engineering who worked for Westinghouse Corporation. Farnsworth showed Zworykin not only his lab but also examples of most of his key innovations, including his image dissector. Zworykin expressed admiration for the devices that he observed, and said that he wished that he had invented the dissector. What Farnsworth did not know was that a few weeks earlier, Zworykin had been hired away from Westinghouse by David Sarnoff, then the managing director and later the president of the Radio Corporation of America (a.k.a., RCA). Sarnoff grilled Zworykin about what he had learned from his trip to Farnsworth’s lab and immediately set him to work on television research. RCA was already a leading manufacturer of radio sets and would soon become the creator of the National Broadcasting Corporation (a.k.a., NBC). After government antitrust regulators forced RCA to divest itself of some of its broadcasting assets, RCA created the American Broadcasting Corporation (a.k.a., ABC) as a separate company[6]. RCA and Farnsworth would remain competitors and antagonists for the rest of Farnsworth’s career.

In 1931, Philco, a major radio manufacturer and electronics corporation entered into a deal with Farnsworth to support his research. The company was not buying out Farnsworth’s company, but was purchasing non-exclusive licenses for Farnsworth’s patents. Farnsworth then moved with his family and some of his research staff to Philadelphia. Ironically, RCA’s television lab was located in Camden, New Jersey, just a few miles away. On many occasions, Farnsworth and RCA could receive the experimental television broadcasts transmitted from their rival’s lab. Farnsworth and his team were working at a feverish pace to improve their inventions to make them commercially feasible. The Federal Radio Commission, later known as the Federal Communications Commission, classified television as a merely experimental communications technology, rather than one that was commercially viable and subject to license. The commission wished to create standards for picture resolution and frequency bandwidth. Many radio stations objected to television licensing because they believed that television signals would crowd out the bandwidth available for their broadcasts. Farnsworth developed the capacity to transmit television signals over a more narrow bandwidth than any competing televisions’ transmissions.

Personal tragedy struck the Farnsworth family in 1932 when Philo and Pem’s young son, Kenny, still a toddler, died of a throat infection, an ailment that today could easily have been treated with antibiotics. The Farnsworths decided to have the child buried back in Utah, but Philco refused to allow Philo time off to go west to bury his son. Pem made the trip alone, causing a rift between the couple that would take months to heal. Farnsworth was struggling to perfect his inventions, while at the same time RCA devoted an entire team to television research and engaged in a public relations campaign to convince industry leaders and the public that it had the only viable television system. At this time, Farnsworth’s health was declining. He was diagnosed with ulcers and he began to drink heavily, even though Prohibition had not yet been repealed. He finally decided to sever his relationship with Philco and set up his own lab in suburban Philadelphia. He soon also took the dramatic step of filing a patent infringement complaint against RCA in 1934.[7]

Farnsworth and his friend and patent attorney, Donald Lippincott, presented their argument before the patent examination board that Farnsworth was the original inventor of what was now known as electronic television and that Sarnoff and RCA had infringed on patents approved in 1930. Zworykin had some important patents prior to that time but had not patented the essential inventions necessary to create an electronic television system. RCA went on the offensive by claiming that it was absurd to claim that a young man in his early twenties with no more than one year of college could create something that well-educated scientists had failed to invent. Lippincott responded with evidence of the Zworykin visit to the Farnsworth lab in San Francisco. After leaving Farnsworth, Zworykin had returned first to the labs at Westinghouse and had duplicates of Farnsworth’s tubes constructed on the spot. Then researchers were sent to Washington to make copies of Farnsworth’s patent applications and exhibits. Lippincott also was able to produce Justin Lippincott, Philo’s old and then retired teacher, who appeared before the examination board to testify that the basic idea of the patent had been developed when Farnsworth was a teenager. When queried, Tolman removed a yellowed piece of notebook paper with a diagram that he had copied off the blackboard in 1922. Although the document was undated, the written document, in addition to Tolman’s oral testimony, may have convinced the board that Farnsworth’s eventual patent was for a novel invention.[8]

The examining board took several months to render a decision. In July of 1935, the examiner of interferences from the U.S. Patent Office mailed a forty-eight page document to the parties involved. After acknowledging the significance of inventions by Zworykin, the patent office declared that those inventions were not equivalent to what was understood to be electronic television. Farnsworth’s claims had priority. The decision was appealed in 1936, but the result remained unchanged. Beginning in 1939, RCA began paying royalties to Farnsworth.

Farnsworth and his family, friends, and co-workers were ecstatic with the outcome when the patent infringement case was decided. For the first time, Farnsworth was receiving the credit and the promise of the money that he thought he was due. However, the price he had paid already was very high. Farnsworth’s physical and emotional health was declining. He was perpetually nervous and exhausted. As unbelievable as it may sound today, one doctor advised him to take up smoking to calm his nerves. He continued to drink heavily and his weight dropped. His company was re-organized as the Farnsworth Television & Radio Corporation and had its initial public offering of stock in 1939. Whether out of necessity or personal choice, Farnsworth’s work in running his lab and his company diminished.

While vacationing in northern, rural Maine in 1938, the Farnsworth family came across a plot of land that reminded Philo of his home and farm outside of Rigby. Farnsworth bought the property, re-built an old house, constructed a dam for a small creek, and erected a building that could house a small laboratory. He spent most of the next few years on the property. Even though RCA had lost several patent infringement cases against Farnsworth, the company was still engaging in public demonstrations of television broadcasts in which it claimed that David Sarnoff was the founder of television and that Vladimir Zworykin was the sole inventor of television. The most significant of these demonstrations was at the World’s Fair at Flushing Meadows, New York. Many reporters accepted the propaganda that was distributed at that event and wrote up glowing stories of the supposedly new invention. Only a few years before, Farnsworth had demonstrated his inventions at the Franklin Institute, but the World’s Fair was a much bigger venue with a wider media audience. In 1949, NBC launched a special televised broadcast celebrating the 25th anniversary of the creation of television by RCA, Sarnoff, and Zworykin. No mention was made of Farnsworth at all.[9]

The FCC approved television as a commercial broadcast enterprise, subject to licensure, in 1939. The commission also set standards for broadcast frequency and picture quality. However, the timing to start off a major commercial venture for the sale of a discretionary consumer product was far from ideal. In fact, the timing of Farnsworth’s milestone accomplishments left much to be desired. His first patents were approved shortly after the nation entered the Great Depression. His inventions created an industry that was already subject to stringent government regulation focused on a related but potentially rival technology: radio. Once television was ready for mass marketing, the nation was poised to enter World War II. During the war, production of televisions and many other consumer products ceased and resources were devoted to war-related materiel. Farnsworth’s company and RCA both produced radar and other electronics equipment. Farnsworth’s company also produced wooden ammunition boxes. Farnsworth allowed the military to enjoy free use of his patents for radar tubes.[10]

Farnsworth enjoyed royalties from his patent for the rest of his life. However, his two most important patents were his earliest inventions. The patents were approved in 1930 for a duration of seventeen years. In 1947, the patents became part of the public domain. It was really only in the late 1940s and 1950s that television exploded as a popular consumer good, but by that time Farnsworth could receive no royalties for his initial inventions. Other, less fundamental components that he had patented did provide him with some royalty income. Before the war, Farnsworth’s company had purchased the Capehart Company of Fort Wayne, Indiana, and eventually closed down their Philadelphia area facility and moved their operations entirely to Indiana. A devastating wildfire swept through the countryside in rural Maine, burning down the buildings on Farnsworth’s property, only days before his property insurance policy was activated. Farnsworth’s company fell upon hard times, as well, and eventually was sold to International Telephone and Telegraph. Farnsworth’s health never completely recovered, and he took a disability retirement pension at the age of sixty and returned to Utah. In his last few years, Farnsworth devoted little time to television research, but did develop devices related to cold fusion, which he hoped to use to produce abundant electrical power for the whole world to enjoy. As of now, cold fusion has not been a viable electric power generator, but it has proved useful in neutron production and medical isotopes.

Farnsworth died in 1971 at the age of sixty-four. At the time of his death, he was not well-known outside of scientific circles. His hopes and dreams of television as a cultural and educational beacon to the whole world had not been realized, but he did find some value in at least some of what he could see on the screen. About two years before he died, Philo and Pem along with millions of other people around the world saw Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon. At that moment, Philo turned to his wife and said that he believed that all of his work was worthwhile.

Farnsworth’s accomplishments demonstrated that a more or less single inventor, with the help of a few friends, family members, and paid staff, could create significant and useful inventions that made a mark on the world.[11] In the long run, corporate product development by rivals such as RCA surpassed what he could do to make his brainchild marketable. Farnsworth had neither the means nor the inclination to compete with major corporations in all respects. But he did wish to have at least some recognition and some financial reward for his efforts. Unfortunately, circumstances often wiped out what gains he received. Farnsworth also demonstrated that individuals lacking paper credentials can also accomplish significant achievements. With relatively little schooling and precious little experience, Farnsworth developed devices that older and more well-educated competitors could not. Sadly, Farnsworth’s experiences display the role of seemingly chance events in curbing personal success. Had he developed his inventions a bit earlier or later, avoiding most of the Depression and the Second World War, he might have gained much greater fame and fortune. None of us, of course, choose the time into which we are born.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. He is the co-author of Institutional Constraint and Policy Choice: An Exploration of Local Governance and co-editor of Kentucky Government, Politics, and Policy. Dr. Clinger is the chair of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board, a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association, and a former firefighter for the Falmouth Volunteer Fire Department.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] Schwartz, Evan I. 2002. The Last Lone Inventor: A Tale of Genius, Deceit, and the Birth of Television. New York: HarperCollins.

[2] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/einstein-s-legacy-the-photoelectric-effect/

[3] Schwartz, op cit.

[4] Schwartz, op cit.

[5] Jewkes, J. “Monopoly and Economic Progress.” Economica, New Series, 20, no. 79 (1953): 197-214

[6] Schwartz, op cit.

[7] Schwartz, op cit.

[8] Schwartz, op cit.

[9] Schwartz, op cit.

[10]Schwartz, op cit.

[11]Lemley, Mark A. 2012. “The Myth of the Sole Inventor.” Michigan Law Review 110 (5): 709–60.

James C. Clinger, Ph.D., is an emeritus professor of political science at Murray State University. His teaching and research has focused on state and local government, public administration, regulatory policy, and political economy. His forthcoming co-edited book is entitled Local Government Administration in Small Town America.

James C. Clinger, Ph.D., is an emeritus professor of political science at Murray State University. His teaching and research has focused on state and local government, public administration, regulatory policy, and political economy. His forthcoming co-edited book is entitled Local Government Administration in Small Town America.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clive.jpg

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clive.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Napoleon_sainthelene.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Napoleon_sainthelene.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Bouchot_-_Le_general_Bonaparte_au_Conseil_des_Cinq-Cents.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napoleon#/media/File:Bouchot_-_Le_general_Bonaparte_au_Conseil_des_Cinq-Cents.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.