The Federalists on Diffusion of Power in American Government to Thwart Absolute Monarchy as Held by King Louis XIV

In 1992, U.S. Supreme Court Justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, succinctly and eloquently summed up the essence of our federalist form of government:

“federalism secures to citizens the liberties that derive from the diffusion of sovereign power.” New York v. United States, 505 U. S. 144, 181 (1992)

Power is diffused among branches and levels of government, so that no one branch can become any more powerful than any other—and the architects of our government were purposeful in this construction.

They did so because they were inherently distrustful of overly centralized power, because they knew that power could be abused, especially the power of an executive, probably the greatest threat to individual liberty. Both Federalist 69 and Federalist 70 focus on the dangers of concentrated or overly powerful chief executives, and how that power ought to be reined in, and while Federalist 69 spends a tremendous amount of time focusing on the English monarchy (and Federalist 70 looks at Ancient Rome), the Federalist’s authors (Madison, Hamilton, and Jay) were well-aware of the recent history of France’s Bourbon monarchs, especially King Louis XIV, the self-proclaimed “Sun King.”

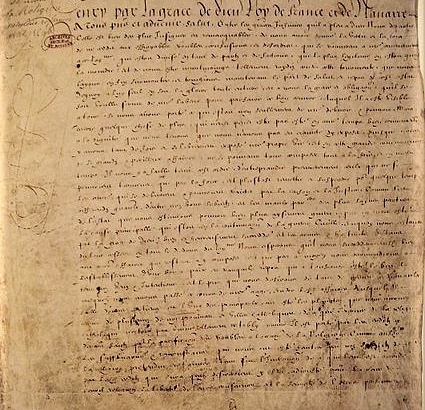

Louis XIV had been coronated when he was only 4, and while contemporaneous observations noted only a casual interest in ruling while he was a boy, when he assumed true personal rule of France in 1661 (following the death of Cardinal Mazarin, the king’s Chief Minister), he worked to ensure that his regal power was both consolidated and secure—building on the tutelage of his mother, Queen Anne, and having witnessed the chaos of a series of French civil wars (The Fronde) as a boy.

These civil wars were of deep concern to him—from both a standpoint of his personal safety and from the standpoint of ensuring his power. Louis, in turn, began to enact a series of reforms to strengthen his role as an “absolute monarch.” While there was a legislature, and there were ministers, Louis served to create a royal civil service corps that were loyal to the crown itself, while at the same time making requirements of both the titled and military aristocracy that served to weaken their power over time.

By making the privileges of aristocracy dependent upon presence and participation at court, the king took both the political and military aristocrats away from their estates—placing them under direct scrutiny of the king and those closest to him, while frustrating any efforts that could undermine Louis’ hold on power (or present a military threat to him).

While it is apocryphal, given the concentration of power by the monarch, the king is reported to have said, “I am the state!”

It is interesting to note that all three of the Federalist’s authors viewed this concentration of power with deep skepticism, but for widely different reasons.

James Madison, one of Thomas Jefferson’s closest friends, shared Jefferson’s affinity for the French generally, but of the three authors of the Federalist essays was probably the most-skeptical of concentrated power from a political perspective, and would have seen the concentration of power as not just a threat to individual rights but also as politically unsound in the long term, something that was proven right decades after Louis XIV’s rule, when the French people revolted.

In contrast, Alexander Hamilton, the author of Federalists 69 and 70, believed in greater concentration of power in the federal government, as well as greater concentration of power in the executive branch. That being said, Hamilton was no fan of the French, and ultimately tried to start a war with the French, despite their assistance to America during the Revolution.

But it was John Jay whose antipathy toward the French monarchy was deeply personal—and who certainly had no love for King Louis XIV.

Jay was raised as a Huguenot, a French protestant sect. The Huguenots were persecuted for a very long time by the French government, until the 1598 Edict of Nantes granted them extensive religious freedom.

But in October 1685, King Louis XIV issued the Edict of Fontainebleu, which revoked the freedoms granted nearly a century earlier (Louis may have done this to placate the Catholic Church, whose political power he had also been trying to diffuse). Persecution of the Huguenots began anew, and John Jay’s great-grandfather sent his wife and children to England to avoid being targeted. As a result, Jay’s great-grandfather had his property confiscated, and he eventually joined his family in England.

When Jay was born in America, he was raised in Rye, New York, and educated in a French Huguenot church school in the next town, New Rochelle named for La Rochelle, a Huguenot center in France.

There is no doubt that his family’s experience colored his own views of the relationship between a central government and the rights of citizens, especially when it came to the freedom to worship and the right to enjoy private property. Interestingly enough, Hamilton, too, had at least one Huguenot ancestor, a grandfather, and this may have contributed toward his antipathy toward the French as well.

To be certain, whether based upon familial experience or an overall approach to political philosophy (and most likely a combination of the two), the authors of the Federalist saw that the political machinations and concentration of absolute monarchic power during the reign of King Louis XIV as something to not just avoid, but to actively work against.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/French_Revolution#/media/File:Anonymous_-_Prise_de_la_Bastille.jpg

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!