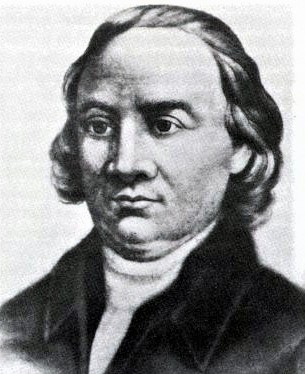

John Morton of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia Assembly Speaker, First and Second Continental Congress Member, Sheriff, Judge, and Declaration of Independence Signer

In the 2016 and 2020 general elections, Pennsylvania was considered a “battleground state” and a “swing state.” It seems that not much has changed since 1776.

Pennsylvania’s political landscape and physical location insulated it to some extent from the revolutionary fever of New England. The stability of the Colonial government was popular among many Pennsylvanians, with the Penn family ruling over the colony since 1681 when William Penn received the land grant from King Charles II. Revolutionary activists were considered a threat to this stability and a personal threat to the power and wealth of the Penn family. Even in the spring of 1776, Pennsylvania’s official political position was opposition to independence. Fortunately, Philadelphia was somewhat central among the colonies and was chosen as the place where delegates from each of the colonies would meet.

The state with the most signers of the Declaration of Independence was Pennsylvania with nine, leading one to believe that the colony was among the most united in favor of independence. However, six of the nine were not even present on the critical days of voting for independence. In the spring of 1776, a more apt description of the situation in Pennsylvania might be “chaos.” A clash of the more radical against the ruling class was in play. John Dickinson and Robert Morris were strong supporters of the status quo, preferring reconciliation with Britain rather than revolution. Pennsylvania’s provincial legislature had instructed its delegates to the Second Continental Congress to vote against independence.

In late May, with the backing of the Second Continental Congress, the radicals effectively orchestrated a coup to create a new constitution and government. A newly created and short-lived Provincial Conference, consisting of those arguing for independence, replaced the existing legislature and, as one of the existing legislature’s last acts, the Assembly gave new instructions to the delegates at the Continental Congress to vote for independence. Among the five delegates to the Continental Congress remaining on July 1, only two of them, Ben Franklin and James Wilson were in favor of independence; John Dickinson and Robert Morris were not in favor when the first vote for independence was taken on July 1. John Morton was on the fence, somewhat surprising since, in his last act as Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, he signed the document giving instructions to the Pennsylvania delegation to vote in favor of independence. Several other delegates opposed to independence had become frustrated and either resigned or simply ceased attending the Congress.

When the final vote for independence was taken in the Congress on July 2, Dickinson and Morris abstained, Morton finally declared support, ensuring a 3-0 vote for independence. Thus, John Morton became Pennsylvania’s swing vote and the man largely responsible for ensuring a “yes” vote for independence on July 2, 1776. So, who was this swing voter?

John Morton was born in 1725. He was a descendent of a Finnish family which had come to the colonies in the mid-17th century. His father died while John’s mother was pregnant. His mother remarried an English farmer and surveyor. John had little formal education, but his stepfather home-schooled John, giving him the ethical and practical education he needed to succeed in life.

At 31, he was elected to the Pennsylvania Assembly, Pennsylvania’s legislative branch, where he remained for all but two years until the Assembly’s dissolution in 1776, at which time he was the Assembly’s Speaker. His two years outside of the Assembly were when his county’s sheriff died and Morton was appointed sheriff.

Among his other political positions, he was Justice of the Peace, Presiding Judge of the Court of General Quarters Session, Common Pleas of the County of Chester, Associate Judge of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania and Justice of Orphan’s Court.

Morton’s first responsibility for petitioning the King for redress of rights was his appointment to the Stamp Act Congress in 1765. From that first act of the colonists until the final vote on July 2, 1776, the colonists’ primary objective was not to seek independence, but to protest unjust actions of the British Parliament and to remain loyal to the mother country by seeking reconciliation. The repeated refusal of the British Parliament and King to consider their requests over the subsequent 10 years drove the colonists to unite for independence in the end.

So highly regarded was Morton in Pennsylvania’s Assembly that he was chosen to represent Pennsylvania in both the First and Second Continental Congresses. His decisiveness on July 2 was critical since only Pennsylvania and Delaware had not yet committed to approving Richard Henry Lee’s resolution “that these united colonies are and of right ought to be free and independent states.” Morton’s Yea vote may have been the primary reason the resolution was approved by the Congress and for our annual celebration of Independence Day on July 4. Unfortunately, Morton is not represented on John Trumbull’s famous portrait of the Continental Congress meeting on June 28, 1776, when the Committee of Five presented its draft to the Congress.

Morton thereafter served as Chairman of the Committee of the Whole that wrote the Articles of Confederation, the document under which the United States operated during the Revolutionary War. He was the first of the signers of the Declaration of Independence to die, in 1777, not living to see the adoption of the Articles of Confederation.

During the Revolutionary War, the British destroyed the Morton family home and its contents, including many of Morton’s papers, leaving little documentary evidence of his role in state and national politics. Morton is one of the least known signers of the Declaration of Independence, but one without whom the document may not have come into existence.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Sources:

https://www.nps.gov/inde/learn/historyculture/resources-declarationofindependence.htm

http://dev.ushistory.org/pennsylvania/birth2.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_colonial_governors_of_Pennsylvania

https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Franklin/01-22-02-0280

https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/facts-1776

https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/blog/trumbull

https://archive.schillerinstitute.com/educ/hist/eiw_this_week/v1n17_jul1_1776.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_delegates_to_the_Continental_Congress#Pennsylvania

https://staffweb.wilkes.edu/harold.cox/legis/indexcolonial.html

https://www.revolutionary-war.net/john-morton/

https://www.dsdi1776.com/john-morton/

http://dev.ushistory.org/declaration/signers/morton.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stamp_Act_Congress

https://archive.org/details/biographicalsket00lossing/page/262/mode/2up?q=morton

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!