Educating a Free People to Secure the Blessings of Liberty for Future Generations of Americans

Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

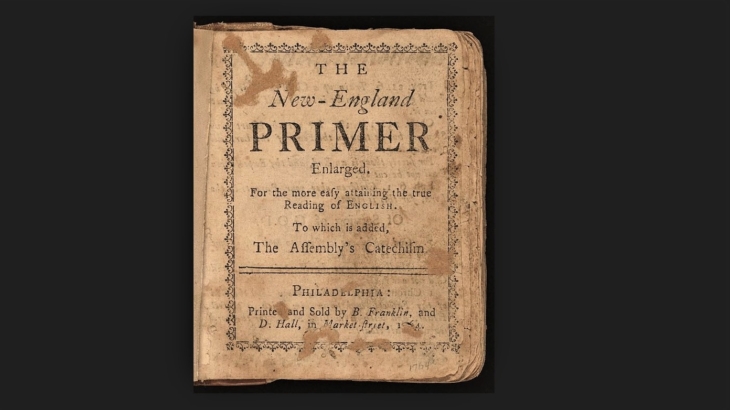

The New England Primer was an educational book, first published in the colonies in the 1690s. For over 100 years, it was used by parents to teach their children to read. Even more than that, the selections of readings – which included plays and poetry – in the primer were meant to give lessons that taught children the importance of morality and virtue. The book was especially popular in New England colonies, where Americans had been enjoying a large degree of political independence from Great Britain and personal freedom in their individual lives. The importance of civic virtue in a republic, as taught by the lessons in the primer, were described by several prominent New Englanders at the time of the American Founding.

Samuel Williams, a professor at Harvard College, wrote about the importance of education in The Natural and Civil History of Vermont in 1794. “Among the customs which are universal among the people, in all parts of the state,” Williams wrote, “one that seems worthy of remark, is, the attention that is paid to the education of children.”[1] Williams continued:

“The aim of the parent, is not so much to have his children acquainted with the liberal arts and sciences; but to have them all taught to read with ease and propriety; to write a plain and legible hand; and to have them acquainted with the rules of arithmetic, so far as shall be necessary to carry on any of the most common and necessary occupations of life.”

In addition to be useful in their daily lives, this education was also meant to shape them into being good citizens.

“All the children are trained up to this kind of knowledge: They are accustomed from their earliest years to read the Holy Scriptures, the periodical publications, newspapers, and political pamphlets; to form some general acquaintance with the laws of their country, the proceedings of the courts of justice, of the general assembly of the state, and of the Congress, &c. Such a kind of education is common and universal in every part of the state.”

This education produces “plain common good sense” as well as “virtue, utility, freedom, and public happiness,” all of which are especially important among citizens in a free society. This view of the purpose of education was also expressed by an anonymous author in a Boston essay titled The Worcester Speculator No. VI in 1787. “If America would flourish as a republic,” he wrote, “she need only attend to the education of her youth. Learning is the palladium of her rights—as this flourishes her greatness will increase.”[2] The author continued:

“[I]n a republican government, learning ought to be universally diffused. Here every citizen has an equal right of election to the chief offices of state. … [E]very one, whether in office or not, ought to become acquainted with the principles of

civil liberty, the constitution of his country, and the rights of mankind in general. Where learning prevails in a community, liberality of sentiment, and zeal for the public good, are the grand characteristics of the people.”

As proven by the effectiveness of The New England Primer, the Worcester Speculator especially emphasized the usefulness of literature for inculcating virtue and morality in students. “If we would maintain our dear bought rights inviolate,” he wrote, “let us diffuse the spirit of literature: Then will self-interest, the governing principle of a savage heart, expand and be transferred into patriotism: Then will each member of the community consider himself as belonging to one common family, whose happiness he will ever be zealous to promote.”

Benjamin Rush of Pennsylvania also wrote about the purpose of education in ways very similar to that of New England. In his A Plan for the Establishment of Public Schools and the Diffusion of Knowledge in Pennsylvania, Rush described the “influence and advantages of learning upon mankind.”[3]

I. It is friendly to religion, inasmuch as it assists in removing prejudice, superstition, and enthusiasm, in promoting just notions of the Deity, and in enlarging our knowledge of his works.

II. It is favorable to liberty. A free government can only exist in an equal diffusion of literature. Without learning, men become savages or barbarians, and where learning is confined to a fewpeople, we always find monarchy, aristocracy, and slavery.

III. It promotes just ideas of laws and government.

Rush was particularly concerned with the effect education – especially through the teaching of history – should have on the citizen in a free republic. “He must watch for the state as if its liberties depended upon his vigilance alone,” Rush wrote, “but he must do this in such a manner as not to defraud his creditors or neglect his family.” Rush continued:

“He must love private life, but he must decline no station, however public or responsible it may be, when called to it by the suffrages of his fellow citizens. … He must love character and have a due sense of injuries, but he must be taught to appeal only to the laws of the state, to defend the one and punish the other. He must love family honor, but he must be taught that neither the rank nor antiquity of his ancestors can command respect without personal merit. … He must be taught to love his fellow creatures in every part of the world, but he must cherish with a more intense and peculiar affection the citizens of Pennsylvania and of the United States.”

The lessons in morality and civic virtue these authors found most important in a free republic were promoted well by the fundamental education students received through The New England Primer well into the eighteenth century.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

[1] Samuel Williams, The Natural and Civil History of Vermont, 1794, available at https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/lutz-american-political-writing-during-the-founding-era-1760-1805-vol-2.

[2] The Worcester Speculator, No. VI, 1787, available at https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/lutz-american-political-writing-during-the-founding-era-1760-1805-vol-1.

[3] Benjamin Rush, A Plan for the Establishment of Public Schools and the Diffusion of Knowledge in Pennsylvania, 1786, available at https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/lutz-american-political-writing-during-the-founding-era-1760-1805-vol-1.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_England_Primer#/media/File:New-England_Primer_Enlarged_printed_and_sold_by_Benjamin_Franklin.jpg

The importance of a well rounded, traditional and classical education cannot be overstated. We must return our schools today to those roots.