Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

“…that the King with and by the authority of parliament, is able to make laws and statutes of sufficient force and validity to limit and bind the crown, and the descent, limitation, inheritance and government thereof” is founded on the principles of liberty and the British constitution: And he that would palm the doctrine of unlimited passive obedience and non-resistance upon mankind, and thereby or by any other means serve the cause of the Pretender, is not only a fool and a knave, but a rebel against common sense, as well as the laws of God, of Nature, and his Country…These are their bounds, which by God and nature are fixed, hitherto have they a right to come, and no further…The sum of my argument is, That civil government is of God…That this constitution is the most free one, and by far the best, now existing on earth: That by this constitution, every man in the dominion is a free man: That no parts of his Majesty’s dominions can be taxed without their consent: That every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature…” – James Otis, Rights of British Colonies Asserted and Proved, pamphlet, 1763.

James Otis, Jr. was born in and lived all his life in Massachusetts. He was a contemporary of both John and Samuel Adams and was a prominent and effective proponent of American independence. He lived from 1725 to 1783.

Known for his pamphlet “Rights of British Colonies Asserted and Proved,” published in 1763, he was very offended by the Writs of Assistance adopted by the British government in 1761. Otis may or may not have coined the phrase “Taxation without representation is tyranny” but he certainly believed and proclaimed it. According to the Smithsonian Magazine (https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/transformative-patriot-who-didnt-become-founding-father-180963166/),

“As John Adams told it, the American Revolution didn’t start in Philadelphia, or at Lexington and Concord. Instead, the second president traced the nation’s birth to February 24, 1761, when James Otis, Jr., rose in Boston’s Massachusetts Town House to defend American liberty. That day, as . . . a rapt, 25-year-old Adams—listened, Otis delivered a five-hour oration against the Writs of Assistance, sweeping warrants that allowed British customs officials to search any place, anytime, for evidence of smuggling. . . . Otis denounced the British king, parliament, and nation as oppressors of the American colonies—electrifying spectators. ‘Otis was a flame of fire,’ Adams recalled years later. ‘American Independence was then and there born.…Then and there was the first…opposition to the arbitrary claims of Great Britain.’”

We say Washington was the father of our country and Madison was the father of the Constitution. According to Adams, we likewise need to say that Otis was the father of our independence.

Tyranny was an issue for our revolutionary forefathers but it was not the primary issue. The primary issue was legitimacy or, more accurately, the lack of legitimacy. The lack of legitimacy created the tyranny under which our American ancestors were then living, and that lack of legitimacy was due to the absence of the consent of the governed. The absence of this consent could have been remedied by the British government’s granting their American colonies representation in Parliament but it was too arrogant and stubborn to do so. They paid for this mistake with the loss of their American empire.

Looking back with hindsight, one may ask why the British made this political blunder. Careful arithmetic would have shown the numerical threshold beyond which they should not go, and they could have granted the Americans a safe number of representatives in Parliament, thereby acquiescing to their demand and quieting the uproar. This would have been a practical solution, but the British were not interested in a practical solution. They adhered to the principle that the American colonists were neither citizens nor subjects but vassals without rights totally subject to rule from London.

One might also reply that each American colony had a legislative assembly, and that is true. But, according to the complaints against the British government Jefferson listed in the Declaration of Independence, by the 1760s those assemblies had been reduced to irrelevance.

We would be remiss if we did not remember that King George III had ascended the throne in 1760 at the age of 22 and that the French and Indian War (1754-1763) was underway at this time. This war and its aftermath created severe financial problems for the treasuries of both Britain and France which, in turn, then led to ill-fated attempts to raise taxes and ultimately to both the American and French Revolutions.

Not only had the French and Indian War been costly to fight, it left the British with a very long western frontier to defend, a frontier that extended all the way to the Mississippi River. This was the time of Daniel Boone when American settlers wanted to move westward past the Appalachians. Defending this frontier was going to be costly. Thereby came the need for tax measures such as the Stamp Act.

A line in the Otis quote at the beginning of this essay is especially informative:

“The sum of my argument is . . . That this constitution [the British constitution] is the most free one, and by far the best, now existing on earth: That by this constitution, every man . . . is a free man: That no parts of his Majesty’s dominions can be taxed without their consent: That every part has a right to be represented in the supreme or some subordinate legislature.”

Otis and many others correctly believed the existing British constitution, based on the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and the English Bill of Rights of 1689, was “by far the best now existing on earth.” The problem was that King George III and Parliament had corrupted it (as Edmund Burke correctly observed) and thereby had intolerably violated the natural rights of their fellow citizens in America. When the British created their Commonwealth of Nations many years later, knowingly or not, they followed the principles Otis enunciated in 1763.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg

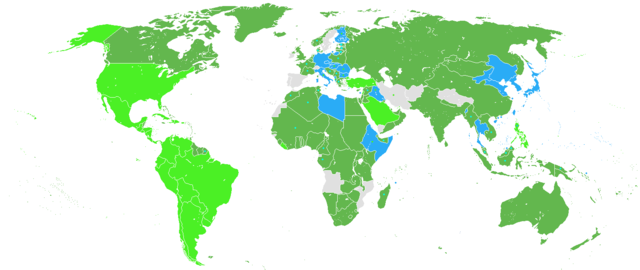

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower#/media/File:Embarkation_of_the_Pilgrims.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allies_of_World_War_II#/media/File:Map_of_participants_in_World_War_II.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allies_of_World_War_II#/media/File:Map_of_participants_in_World_War_II.png https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German-occupied_Europe#/media/File:Europe_under_Nazi_domination.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/German-occupied_Europe#/media/File:Europe_under_Nazi_domination.png

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.