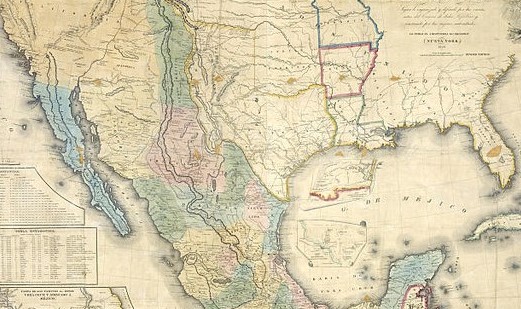

February 2, 1848: Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo Ends Mexican-American War, Annexes West

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed shortly after James Wilson Marshall discovered gold flakes in the area now known as Sacramento. Border disputes would continue, but the treaty ended the Mexican-American War (1846-1848) and added a large swath of western territory broadly expanding the United States. It would make up Arizona, California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, Washington, Oregon, Texas, and parts that would later make up Oklahoma, Colorado, Kansas, Wyoming, and Montana. The new lands acquired from Mexico stirred sectional passions about the expansion of slavery in the West that helped lead to the Civil War after being temporarily settled by the Compromise of 1850.

Americans almost never think about the Mexican-American War. We don’t often pause to consider its justifications or results. We may know that it served as the training ground of just about everyone who became famous in the Civil War, but details of how, where, or why they fought that prequel might as well be myth. Most of us have no idea how many of our place names have their roots in its participants. Outside of a little-understood line in the Marine Hymn, we almost never hear anything about how we won it. And almost no American knows anything about the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo that formally ended it: not its name, not its terms, not who signed it, and not the drama that went into creating a Mexican government willing to enter it.

We have good reason to studiously remember to forget these details. Guadalupe-Hidalgo was an unjust treaty forced on a weaker neighbor to conclude our least-just war. It was also hugely consequential, and we spectacularly benefited from imposing it on Mexico.

The War Itself

The war’s beginnings lay in the unsettled details of Texas’s War of Independence. Yes, Mexican President Santa Anna had signed the so-called Treaties of Velasco while held prisoner after the Texian victory at San Jacinto in 1836, but Mexico both: (a) refused to ratify them (so never formally recognizing Texas’s independence); and (b) simultaneously argued that the unrecognized republic’s Southern border lay at the Nueces River, about a hundred and fifty (150) miles north of the Rio Grande (as Texas noted the Treaties of Velasco would have determined).

All this came to matter when James K. Polk won the Presidency in 1844. He had campaigned on a series of promises that, for our purposes, included: (a) annexing Texas; and (b) obtaining California (and parts of five (5) other modern states) from Mexico.[1], [2] Part one came early and easily, as he negotiated Texas’s ascension to the Union in 1845. But when the Mexican government refused to meet with his emissary sent to negotiate the purchase of the whole northern part of their country,[3] in pursuit of a fallback plan, President Polk sent an army south to resolve the remaining ambiguity of the Texas-Mexico border. That army (contemporaneously called, with greater honesty than later sources usually admit, the “Army of Occupation”) under the command of Zachary Taylor went to “guard” the northern shore of the Rio Grande. It took some doing, including the shelling of Matamoros (a major Mexican port city on the uncontested Southern shore of the river), but Taylor eventually managed to provoke a Mexican response. Mexican forces crossed the river to drive back the attacking Americans, in the process prevailing in the Thornton Skirmish and destroying Fort Brown.[4]

President Polk styled these actions a Mexican invasion of America that had killed American soldiers on American soil. On that basis, he sought and received a Congressional declaration of war. Days after receiving it (and in a time before even telegraphs, the distances involved – and coordination with naval forces in the Pacific make that timing revealing), American forces invaded Mexico in numerous arenas across the continent, seizing modern-day Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, and Nevada; simultaneously, American settlers declared the “independence” of the Republic of California (the “independence” of which lasted no more than the twenty-five (25) days between their ineffective declaration and the arrival of the American military in Sonoma Valley).

But the achieving of Polk’s aims didn’t end the war. Mexico didn’t accept the legitimacy or irreversibility of any of this. Polk ordered Taylor’s army South, to take Monterrey and press into the Mexican heartland. Eventually, when that, too, failed to alter Mexican recalcitrance, President Polk sent another army, under the Command of Winfield Scott, to land in the Yucatan and follow essentially the same route Cortez had toward Mexico City. Like the conquistadors of old, that force (including Marines) would head for “the Halls of Montezuma” (the last Aztec king).

All this was controversial immediately. Abraham Lincoln condemned the entire escapade from the floor of Congress as “unnecessarily and unconstitutionally commenced.” Henry Clay called it an act of “unnecessary and [ ] offensive aggression.” Fresh out of West Point, Ulysses S. Grant fought in the war, but after his Presidency would reflect that “I do not think there was ever a more wicked war than that waged by the United States on Mexico.” And as the war raged, Washington, D.C. became consumed with the question of what all this new territory would do to the delicate balance established by the Missouri Compromise; was the whole war just a scheme to create new slave states? It was still only 1846, with the war’s outcome still unclear, when Pennsylvania Congressman David Wilmot sought to amend an appropriations bill (meant to authorize the funds to pay for peace) with “the Wilmot Proviso,” a bar on slavery in any formerly Mexican territory.[5]

Victory and Then What?

Wicked or not, the plan worked. American forces promptly took Mexico City in September of 1847.

As Mexico City fell (with its President fleeing and the Foreign Minister declared acting-President), the collapsing Mexican Government proposed terms of peace (under which Mexico would retain all of modern New Mexico, Arizona, Southern California, and much of Nevada), designed to further pique Washington’s emerging divide by giving the U.S. only territory north of the free/slave divide established by the Missouri Compromise. But the Mexican government’s ability to deliver even those terms (which would have reversed enormous battlefield losses) was highly suspect; Jefferson Davis, who had fought in most of the war’s battles before being appointed a Mississippi Senator, warned Polk that any Mexican emissaries coming to Washington to negotiate based on it would see the talks go longer than their government’s survival and the negotiators labelled traitors and murderers, should they ever try to return home. And he was pretty clearly right: the people of Mexico were not happy about any of this: not with the loss of more than ½ their territory, not with the conquest of their capital, and not with the collapse of the government that was supposed to prevent anything of the sort from happening.

So how do you end a war and go home when there’s no one left to hand back the pieces to?

That was the rub. The Americans in Mexico City didn’t want to stay. The whole war had been controversial and America having to occupy the entirety of Mexico sat particularly poorly with its opponents. The Wilmot Proviso hadn’t gone away either and Senators were already arguing that it would need to be incorporated into any peace treaty with Mexico (whomever that meant). And there was no one with the ability to clearly speak for Mexico to negotiate anything anyway.

Eventual Treaty with Mexico’s Acting Government

It would take almost all of the remainder of Polk’s presidency to resolve these problems. Eventually, the acting Mexican government became willing to sign what America had decided the terms of peace required. Those terms? America would pay Mexico $15 million.[6] America would assume and pay another $3.25 million of Mexico’s debts to Americans.[7] As the GDP of California, alone, is estimated at $3.1 trillion for 2019, the purchase price was a bargain, to say the least. Mexico would renounce all rights to Texas and essentially all the rest of the modern American West. All of California (down to the port of San Diego, but not Baja), Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado (and almost all of Arizona)[8] would so change hands; the Republic of Texas’s territories were substantially larger than those of the modern State of Texas, so this renunciation also secured American title to parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming.

Aftermath

So America became the transcontinental republic Jefferson had dreamed of. Polk got to go home with his mission accomplished.[9] America secured title to California weeks after settlers discovered what would become the world’s largest known gold deposits (to that date) at Sutter’s Mill, but before word of that discovery had made it to either Mexico City or Washington.

But America acquired something else with vast territories, and unforeseen riches. It also acquired a renewal of fights over what to do with seemingly limitless, unsettled lands and how to accommodate the evil of slavery within them. Those fights, already underway before Mexico City fell, would scroll out directly into Bleeding Kansas and the Civil War.

Dan Morenoff is Executive Director of The Equal Voting Rights Institute.

Click Here to have the NEWEST essay in this study emailed to your inbox every day!

Click Here to view the schedule of topics in our 90-Day Study on American History.

[1] The complete set also included: (a) resolving the border with Canada of America’s Oregon territory; (b) reducing taxes; (c) solving the American banking crises that had lingered for decades; and (d) leaving office without seeking reelection. Famously, Polk followed through and completed the full set.

[2] The targeted territory included lands now lying in California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and Colorado.

[3] That was John Slidell, for whom the New Orleans suburb is named.

[4] Mexico so killed Major Jacob Brown, arguably the first American casualty of the war (for whom both the fort-at-issue and the town it became – Brownsville, Texas – were named).

[5] It failed in the House at the time, but exposed the raw power plays that success in (or perhaps entry into) the Mexican-American War would bring to the forefront of American politics.

[6] Depending on how one chooses to calculate the current value of that payment, it could be scored as the equivalent in modern dollars of $507.2 million, $4.04 billion, $8.86 billion, or $9.04 billion. https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/?amount=15000000&from=1848.

[7] The same approaches suggest this worked out to an assumption, in today’s dollars, of another $109.9 million, $876.1 million, $1.91 billion, or $1.96 billion in Mexican obligations. https://www.measuringworth.com/dollarvaluetoday/?amount=3250000&from=1848.

[8] Later, the US would separately negotiate the Gadsen Purchase to acquire a mountain pass through which a railroad would one-day run.

[9] He promptly died on reaching his home in Tennessee; some have noted that this means he was not only the sole President to do everything he promised, but also the perfect ex-President.

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!