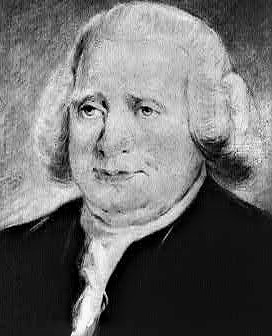

Carter Braxton of Virginia: Planter, Merchant, House of Burgesses and Continental Congress Delegate, and Declaration of Independence Signer

When studying history, it is important to remember a few things. First, historic events were not singular moments as we often view them; instead, they developed as events today do, over time, and as a result of many influences.

Second, it is important to not oversimplify the past because people and events then were as complicated, conflicted, and convoluted as they are today. How people lived, the decisions they made, and the challenges they faced were complex, even if some of the details may have been lost to history.

When reading of the life of Carter Braxton, a signer of the Declaration of Independence from Virginia, it is important to keep these considerations in mind. Born into wealth, Braxton did not, however, live an easy life though it may have been privileged and full of material comforts. He died at an early age, having lost his once significant fortune, yet given the struggles he faced throughout his life, he might be excused for some of these failures.

Braxton was born on September 10, 1736 into one of the wealthiest and most distinguished families in the colonies. He was born on the Newington Plantation, east of Richmond on the Mattaponi River, which connects to the York River and Chesapeake Bay, and sits at the western end of Virginia’s beautiful Middle Peninsula. He was a planter and merchant. His grandfather had immigrated from England, and his father, who received a large land grant from George II, would expand the family’s wealth and prestige, serving frequently in the House of Burgesses from 1718 to 1734. His grandfather on his mother’s side was Robert “King” Carter, a man of great wealth and prominence, who also served in the House of Burgesses, including as Speaker. King Carter even served as the colony of Virginia’s Acting Governor for a year.

From this auspicious beginning, one might assume that Carter led a happy and contented life of comfort. Yet his wealth did not shield him from tragedy. His mother died just a week following his birth, and his father passed away when Carter was only 13. He married Judith Robinson upon leaving the College of William and Mary after only one year, but sadly she also died after they had been married for only two years. Perhaps to ease his grief, he traveled to Europe and England where he learned a great deal about the rulers of his colonial home, knowledge and perspective that would inform his decisions when revolutionary fervor gripped the colonies. After two years in Europe, he returned, marrying a second time in 1760 to Elizabeth Corbin. It is reported that they had 16 children together.

In keeping with family tradition, Braxton served in the House of Burgesses following his return, beginning in 1761. Then, when Peyton Randolph died suddenly in October 1775, he was made a member of Virginia’s delegation to the Second Continental Congress where he would serve for two years.

Carter was loyal to Virginia, but also to the Crown, at first. He was a reluctant revolutionary and argued against independence, fearing that it, and specifically a republican government, would lead to disaster and despotism in the colonies. While disinclined, he continued to work alongside the familiar names of the eventual revolution, including George Washington and Peyton Randolph. He did not relish conflict with the British, and worked to quell it when he could.

One historical incident shows the character and conservative nature of the man, when he worked with Patrick Henry to avoid direct conflict with the Royal Governor Lord Dunmore. Following the events at Lexington and Concord, Dunmore had confiscated gunpowder stored in Williamsburg, Virginia. Militia units were ready to fight over their lost supplies, led by the fiery Patrick Henry. Braxton was able to use the good connections he had through his father-in-law, Richard Corbin, who was serving as receiver general of the Colony, to pay the militia for the gunpowder, thus avoiding a military confrontation.

While Braxton was reluctant, he was not without independence sentiments. While a member of the House of Burgesses, likely as a result of his knowledge of the financial designs England had for the colonies which he learned through his travels there, he signed the Virginia Resolves which asserted that only the House of Burgesses had the right to tax Virginians. He also signed the Virginia Association, a non-importation agreement, and in 1775 became a member of the Virginia Colonial Convention.

Students of history know that there was a raging debate in the colonies at that time regarding independence. Many American leaders wanted England to change its policies toward the American Colonies, but did not support independence, nor did they desire revolution. Carter Braxton was initially of that opinion, and advocated a conservative approach. His essay which was published in June 1776, however, an excerpt of which is below, demonstrates his eventual acceptance of the need for independence:

When depotism had displayed her banners, and with unremitting ardour and fury scattered her engines of oppression through this wide extended continent, the virtuous opposition of the people to its progress relaxed the tone of government in almost every colony, and occasioned in many instances a total suspension of law. These inconveniencies, however, were natural, and the mode readily submitted to, as there was then reason to hope that justice would be done to our injured country; the same laws, executed under the same authority, soon regain their former use and lustre; and peace, raised on a permanent foundation, bless this our native land.

But since these hopes have hitherto proved delusive, and time, instead of bringing us relief, daily brings forth new proofs of British tyranny, and thereby separates us further from that reconciliation we so ardently wished; does it not become the duty of your, and every other Convention, to assume the reins of government, and no longer suffer the people to live without the benefit of law, and order the protection it affords?

So, rather hesitatingly, but eventually, he came to support the Revolution, voted for the Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776, and signed it on August 2, 1776.

In response to his cautious and conservative views about democracy, Braxton was not initially returned to Congress after 1776. He did, however, remain active in Virginia politics and eventually returned to Congress where he served until 1783. He died of a stroke at the age of only 61 in 1797.

Like many of the founders, the revolution was not kind to Braxton. He lent significant financial support to the American Independence effort, including both money and ships, many of which were destroyed. His business was greatly curtailed, and his lands and plantations ransacked and pillaged. He made some unfortunate financial decisions of his own, as well, and ended his life in debt. His reputation as a clear thinker, honorable public servant, and patriot did not suffer, however, from his lack of financial success. He was described by his peers as a sensible and accomplished gentleman, and by others as a man of cultivation and talent. Despite the many challenges and tragedies that punctuated his life, he is remembered most for his honorable service to the cause of liberty.

Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and two grandchildren.

Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and two grandchildren.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

References:

Cruz, Shelly (2014). Carter Braxton, Descendant, Descendants of the Signers of the Declaration of Independence (DSDI), https://www.dsdi1776.com/carter-braxton/

Revolutionary War (2020). Carter Braxton, Revolutionary War: A colorful, story-telling overview of the American Revolutionary War, https://www.revolutionary-war.net/carter-braxton/

Hyneman, C., & Lutz, D. (1983). American Political Writing During the Founding Era, 1760-1805. Liberty Fund, Incorporated. https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/lutz-american-political-writing-during-the-founding-era-1760-1805-vol-1

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!