Relating the American experience to the rise and fall of empires is trickier than it looks. Empires are complicated morally and historically—none more so than the British Empire—and the United States has its own complicated understanding of its relationship with empire.

“Empire” is no longer a morally neutral term. Most people these days believe “empire” is something universally or exclusively bad. And why wouldn’t people believe that? While it is true that the simplistic Marxist critique of imperialism as late-stage capitalism has had much to do with the bad rap for empires, that does not let empire off the hook. Part of the reason the Marxist view took hold was because most empires have been rapacious and exploitative, if not genocidal. Nowhere was that more evident than in the scramble for Africa, when European powers carved up the continent with little effect but suffering and despair for the local populations. Similar results of empire could be seen throughout the Americas and Asia.

However, not all empires are created equal. Even if we agree all empires are in general bad, some empires are way worse than others, just as some bad empires have had some positive effects. In Monty Python’s The Life of Brian, the Middle Eastern radicals sarcastically ask, “What have the Romans done for us?” The question eventually turns to: “Apart from the sanitation, the medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, a fresh water system, and public health, [and peace], what have the Romans ever done for us?”

The line is funny because it is an unexpected contradiction in truths. But it could also be read as a commentary by British actors on the post British empire world. This is not the place to sort out the net positives and negatives of the British empire, nor to explain why the empire eroded over the course of the twentieth century. Here it is only to recognize that the British empire did help bring a measure of order and stability to the international system that certainly was not good for all, but was also more liberal and beneficial than the alternative empires of the time.

In the years around World War II, the British gave up their empire, leaving the question of who would provide order in the international system. During the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union competed over who would fill that gap. Interestingly, neither side called themselves an “empire.” In fact, both sides accused the other of imperialism.

The Soviet fall left the United States as the world’s great superpower, and responsible, in some measure, for providing order and stability lest some other, more pernicious power rise and impose a less favorable order on the world. Americans have struggled with what to do in that role. The country has not hesitated to intervene all around the world, often with lethal force, but it has consistently shied away from picking up an explicitly imperial mantle. Even when the United States joined the European and Japanese imperial scrambles around the turn of the twentieth century, Americans, including expansionists like Theodore Roosevelt, generally avoided the word “empire” for describing their foreign policy ambitions.

Frustrated by America’s inconsistency as a great power, some contemporary critics have encouraged the United States to embrace its role as an explicit empire for good. Eager to make their point, the critics have appealed to the language of the Founders, who often did use “empire” to describe the American experiment.

But that is too simple. The Founders used “empire” in specific ways. In many cases, they meant it roughly as a synonym for the country. Federalist 1 stated that the proposed Constitution was about, “the fate of an empire in many respects the most interesting in the world. It has been frequently remarked that it seems to have been reserved to the people of this country, by their conduct and example, to decide the important question, whether societies of men are really capable or not of establishing good government from reflection and choice, or whether they are forever destined to depend for their political constitutions on accident and force.”

When the Founders did use empire to describe the expansion of the United States, they added important modifiers. Thomas Jefferson’s was the most famous, “we should have such an empire for liberty as she has never surveyed since the creation: & I am persuaded no constitution was ever before so well calculated as ours for extensive empire & self-government.”

Note the common theme. This “most interesting” of empires, this “empire for liberty,” was unique because it was about self-government and freedom internally. If “empire for liberty” sounds now like an oxymoron, that is because it always was. It was an experiment, a new type of empire, built around trying to balance the necessary and inevitable tension between exerting great power and modeling freedom. To make it work, and to revise historian Walter McDougall’s framing, described in his book, Promised Land, Crusader State: The American Encounter with the World Since 1776, the promised land always required the crusader state, and crusader state had to remain the promised land.

It is the inheritance of that tenuous balance that has made subsequent Americans uncomfortable with the word “empire.” That is a good thing. The ugly empires of the nineteenth century clearly were not, and were not trying, to be promised lands of freedom. Without that constraint those empires overreached and fell.

The power and influence of the United States in the world has always strived to be something different. Whatever else that can be said about American expansion and intervention overseas, and there is plenty of room for critique, it has most often been constrained by Americans themselves. Whether through idealistic objectives set by governments in power, contentious domestic politics, or the vocal opposition of small minorities or brave lone voices, the United States has never expanded or intervened without the reminder that such activities threaten the soul of America itself. “She might become the dictatress of the world,” John Quincy Adams said in his famous address on July 4, 1821, but “She would be no longer the ruler of her own spirit.”

From Canada and Mexico, Cuba and the Philippines, Vietnam, and all the way to Afghanistan and Iraq, that reminder has always been there, embedded by the Founders in the American system, meant to constrain all-too-human ambitions of domination. If the United States is to avoid imperial overreach, its people must continue to remember that America’s “glory is not dominion, but liberty,” and always reach accordingly.

Thomas Bruscino is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the United States Army War College. He holds a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio University and has been a historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington, DC and the US Army Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, and a professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. He is the author of A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along(University of Tennessee Press, 2010), and Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare (CSI Press, 2006), and numerous book chapters. His writings have appeared in the Claremont Review of Books, Army History, The New Criterion, Military Review, The Journal of Military History, White House Studies, War & Society, War in History, The Journal of America’s Military Past, Infinity Journal, Doublethink, Reviews in American History, Joint Force Quarterly, and Parameters.

The views and opinions presented are those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of the U.S. Army War College, the U.S. Army, or the Department of Defense.

Click here for American Exceptionalism Revealed 90-Day Study Schedule

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png

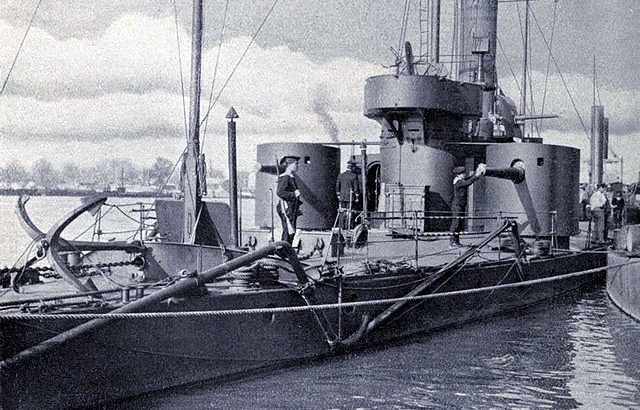

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/British_Empire#/media/File:The_British_Empire.png https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_monitor_Sava#/media/File:SS_Bodrog_1914.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yugoslav_monitor_Sava#/media/File:SS_Bodrog_1914.jpg Thomas Bruscino is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the United States Army War College. He holds a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio University and has been a historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington, DC and the US Army Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, and a professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. He is the author of A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along(University of Tennessee Press, 2010), and Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare (CSI Press, 2006), and numerous book chapters. His writings have appeared in the Claremont Review of Books, Army History, The New Criterion, Military Review, The Journal of Military History, White House Studies, War & Society, War in History, The Journal of America’s Military Past, Infinity Journal, Doublethink, Reviews in American History, Joint Force Quarterly, and Parameters.

Thomas Bruscino is Associate Professor of History in the Department of Military Strategy, Planning, and Operations at the United States Army War College. He holds a Ph.D. in military history from Ohio University and has been a historian at the US Army Center of Military History in Washington, DC and the US Army Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, and a professor at the US Army School of Advanced Military Studies. He is the author of A Nation Forged in War: How World War II Taught Americans to Get Along(University of Tennessee Press, 2010), and Out of Bounds: Transnational Sanctuary in Irregular Warfare (CSI Press, 2006), and numerous book chapters. His writings have appeared in the Claremont Review of Books, Army History, The New Criterion, Military Review, The Journal of Military History, White House Studies, War & Society, War in History, The Journal of America’s Military Past, Infinity Journal, Doublethink, Reviews in American History, Joint Force Quarterly, and Parameters.