Principle of Constitutional Restraints To Prevent the Undermining of Interests of the Entire Union

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

One of the purposes of the Constitution of the United States, according to its Preamble, is “to form a more perfect Union.” It was a long road, however, for that Union to be more perfectly established as under the Constitution in 1787. Before the Constitution, the thirteen original states had agreed to a “firm league of friendship” through a compact known as the “articles of Confederation and perpetual Union.”

In July of 1776, the thirteen states engaged in an act of unity by unanimously declaring themselves “free and independent states” no longer under the political authority of Great Britain. Prior to that, in 1774, the thirteen American colonies took the first official steps toward becoming a formal Union through the Articles of Association, which established the Continental Congress and put them on the path to independence.

The pace at which the states moved from being colonies under the authority of the British Crown, to “free and independent states,” and then to the United States of America seemed to quicken and intensify under the pressure of events during the American Revolution and Revolutionary War. But for decades prior, many Americans had been attempting to establish a formal union between the British Colonies in America, primarily for purposes of mutual defense and the protection of British economic interests among the American colonies. These early efforts ultimately made it possible for the states to formally unite as the United States of America. It was not an easy road, however, as many colonies saw their habits, manners, and economic interests as quite different from those of the other colonies. Pulling these vastly different peoples together as one would be a long, arduous task.

One man who made great strides in uniting the colonies for purposes of mutual defense was Benjamin Franklin. In his Autobiography, Franklin writes of a plan of Union he had proposed in 1754. Anticipating an approaching war with France (which did eventually become the French and Indian War of 1754-1763), the British authorized a congress of commissioners from the colonies to convene in Albany, New York to discuss defensive preparations. Franklin took the opportunity to draw up a more extensive plan by which the colonial defenses would be administered by a general government of the Union.

“I projected and drew a plan,” Franklin wrote, “for the union of all the colonies under one government, so far as might be necessary for defense, and other important general purposes. … By this plan the general government was to be administered by a president-general, appointed and supported by the crown, and a grand council was to be chosen by the representatives of the people of the several colonies, met in their respective assemblies.”

Ultimately Franklin’s plan was rejected by the colonial assemblies, because under it the British retained too much political authority over the colonies, and by the British, because it seemed to grant too much independence and self-government to the colonies. Later, in 1788, Franklin would write,

“I am still of opinion it would have been happy for both sides of the water if it had been adopted. The colonies, so united, would have been sufficiently strong to have defended themselves; there would then have been no need of troops from England; of course, the subsequent pretense for taxing America, and the bloody contest it occasioned, would have been avoided.”

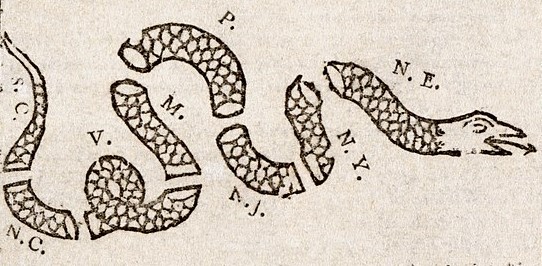

Despite the failure of Franklin’s Albany Plan of Union in 1754, it had an important impact on the public mind of American colonials. Franklin, as a well-known and highly respected public figure, was now identified as the leading advocate of colonial unity, inspiring others to consider the possibility of formal union in the future. Furthermore, to promote the Albany Plan, Franklin introduced one of the most important symbols of the American Revolutionary period in his famous “Join, or Die” slogan under the image of a snake cut into thirteen pieces.

Franklin designed the image and published it in his widely read newspaper The Pennsylvania Gazette on May 9, 1754. Almost two decades later, as the Acts of the British Parliament became more unjust and oppressive in the eyes of American colonists in the 1770s, Franklin’s “Join, or Die” image was revived and inspired many people to join with the patriots, thus making possible the Union that eventually emerged from the American Revolution.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Christopher C. Burkett is Associate Professor of History and Political Science, and Director of the Ashbrook Scholar Program at Ashland University.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/American_Revolutionary_War#/media/File:British_Army_in_Concord_Detail.jpg

Join the discussion! Post your comments below.

Your feedback and insights are welcome.Feel free to contribute!