On this occasion I beat an old horse, just to prove that he is not dead. In this task I am not unlike the rhapsode, Ion, who kept Homer alive by memorizing Homer’s entire poems and reciting them at every opportunity. Unlike Ion, however, I trust that I do not mistake the wisdom of the authors for the wisdom of the rhapsode.

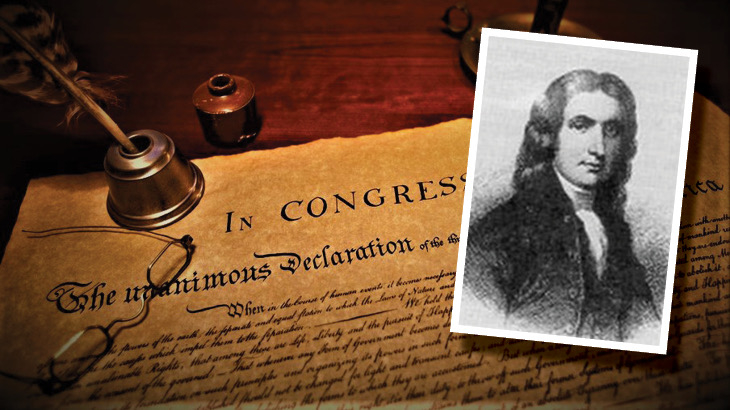

The relation between the Declaration and the Constitution has a different affect today than it did in 1860, when enemies to the more perfect union could find no pillar bearing more weight – and thus to be dislodged – than what they called the “self-evident lie” that “all men are created equal.” Those critics insisted that men indeed are not by nature made equal, nor should be. Today’s enemies of the more perfect union believe that “all men” in 1776 only meant all white males and, moreover, that not even they were by nature made equal though they should be. These critics insist, however, that what nature and history refused to humankind law can create (and they would indeed have all men equalized, the Constitution notwithstanding).

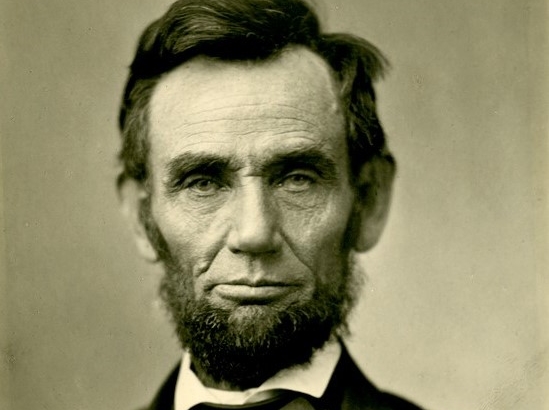

In 1860 nothing and no one so stoutly resisted the enemies of the Declaration than the Defender of the Constitution. Today nothing and no one so stoutly resist the enemies of the Constitution than the Defender of the Declaration. Abraham Lincoln established at Gettysburg that the nation “conceived in liberty” and confirmed “in the proposition that all men are created equal” must conduct its affairs through limited, constitutional union. Today we require to learn that limited, constitutional union can only be justified on the basis of the Declaration of Independence. What we mean, then, when we say that the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution are best friends, is that they are necessary and reciprocal supports for each other.

Two proofs are necessary to complete this argument: first, that the Declaration requires limited, constitutional union and, second, that the Constitution requires the principle of equality founded in laws of nature and creation.

The First Proof: Limited Constitutional Union Is Required

We may restate the first inquiry in the following form: is it true that the rebellion against British monarchy would have been unjustified on any grounds other than the grounds of natural rights, and that natural rights must disclose not only people’s claims to justice but their capacities to realize those claims?

When stated thus, the first proof becomes, I believe, easily realizable. Let’s start with the negative argument. The British constitution and laws in no way recognized a right of revolution. Accordingly, the act of revolution could not have been founded on any positive authority. Moreover, the Americans were not disproportionately harmed, relative to other subjects of the monarchy. Therefore, as far as the conceded rights of Englishmen went, the Americans could have had no beef against the Crown. Although non tallagio non concedendo (“no taxation without consent”) was an established principle of positive right in Britain, it was honored more in the breach than in the practice (given the pervasiveness of rotten borough representation). Americans were no less well represented than many a Briton. Nor could America make any secession claim, since the colonies could not affect an autonomous status conditioning their place in the empire. To have a right to secede, they would have had to begin with voluntary assimilation into the empire. Political forms, which are themselves artifices, cannot derive principles of their conduct from nature as opposed to their architecture.

If the Americans were justified at all, in other words, their justification had to be extra-judicial, extra-political, extra-historical. When we read the Declaration of Independence, we notice not only the broad language of the exordium (“When in the Course of Human Events…”) and the universal principle of the enunciation (“We hold these truths to be self-evident…”), but we can especially notice the particular charges (“the long train of abuses and usurpations”) leveled against the King. It has been frequently noted that the very form of the Declaration’s indictment identifies the King rather than the Parliament as the enemy to America’s liberty. Sometimes this is thought to be a ruse to avoid acknowledging Parliament’s authority (the Americans claimed an interpretation of the British constitution that made them directly subject to the monarch without intervention of the Parliament). A careful reading, however, discloses a substantive and not merely rhetorical argument that highlights the Declaration as an initial charter of government.

Government for the Good of the People…

The first twelve charges against the King (all of them, that is, until the thirteenth, which associates him with the Parliament in opposition to the colonies) actually condemn the King foremost for ignoring the welfare of his subjects. The language of the very first charge is meant to characterize the particulars in all of those that follow:

He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.

Now, the laws invoked by the colonists here are the laws of their colonial legislatures, not any laws of Parliament. Thus, the substance of the charge is that the King, their sovereign, has declined to cooperate in their exertions of lawful and subordinate self- government with an eye to the public welfare. The implicit argument made here, clearly, is that persons are subject to government only for their good, and that argument is a principle that transcends any charter or act of government. It establishes a standard of judgment to which every government of whatever cast is subject, and in the name of which any people, any time, have the right, nay, the “duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.”

…Or Else Legislative Powers Return to the People

Each of the remaining charges against the King reinforces this same principle; each is a particular proof of the universal truth contained in the Declaration’s enunciation. Perhaps none does so, however, so centrally as that in which they accuse him of neglecting the necessary exercise of legislative powers in such a manner as to cause that “the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise.” But this very observation is followed with the particular notice that the result is to expose the people, inadequately provided, “to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.” This observation, then, makes the necessary argument that although in general the purpose of government is to provide for the public welfare, in particular it is to accomplish such acts as the people, otherwise unprovided, cannot so well provide for themselves. And where the constituted government — limited by this purpose — fails, it falls to the people speedily to provide such a government as can respect these limits and accomplish these results.

Each of the charges against the King can be converted into a positive affirmation of the obligations of government. For example, government must respond to “immediate and pressing” needs, relying upon local necessities and judgments wherever delays in execution would be a necessary part of reserving judgment to the highest authority. The needs of people must be accommodated without the cost of them relinquishing “the right of Representation in the Legislature.” Legislatures must operate in such a manner as to remain readily accessible to the people and with recourse to public records. Dissent must be respected within the assemblies that conduct the public business. Free movement of persons into and out of the country is a fundamental part of the liberty of citizens. Judicial powers must be independent of executive will and be empowered to render justice to persons. Citizens should not be burdened with excessive requirements to support public officers. A military administration is incompatible with public liberty, and the military must be subordinate to and dependent upon the civil power.

Architecture of Government Founded in Universal Principles

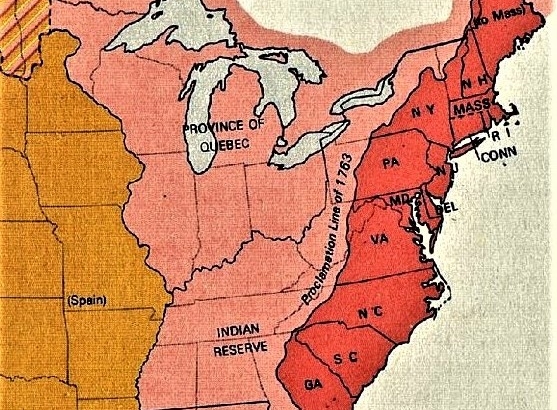

The architecture of government sought in these affirmations is founded in universal principles and not the English constitution. If there were any doubt about this, the doubt would be resolved not merely by comparing this to the actual English constitution of the day, but also by considering the weighty charge against the King concerning his activities in Canada. For there, the revolutionaries held, he abolished “the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing there in an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies.” Note that this produces a different picture of English laws operating in Canada. If Canada, previously French, were being anglicized along lines different from what obtained in the thirteen colonies, the thirteen colonies were not anglicized. Moreover, the demand for a clear-cut demarcation among the powers of government — executive, legislative, and judicial — derived not from English practice but from a universal principle.

This design of limited constitutionalism, further, was nothing less than imitating in human artifice the order of nature reflected in the powers of God affirmed in the Declaration. God held the three powers of effective order, legislative, executive and judicial. He legislated “the Laws of Nature and of Nature’s God;” regarding humans he was the executor, for “they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights;” and he was appealed to as “the Supreme Judge of the world for the rectitude of our intentions.” God, in other words, united the three powers of effective order in his own person. He could do so precisely because he exists in an order above man and respecting which no “consent” to his rule could be demanded. No man is God’s equal, while every man is any king’s moral equal.

Therefore, no rule by men could assemble the three powers of effective order in the same man or body of men, without creating the presence of a power superior to man. The necessity of consent derives from the truth that “all men are created equal,” meaning that no one man is by nature the ruler of any other. In that circumstance, just rule among men can eventuate only from consent. To be effective, however, such consent must be limited by prudential separations of power that will prevent god-like domination. Men will fail to obtain such good as God has ordained for them unless they gather together in effective political union, but effective political union requires limited, constitutional government.

The Declaration needs limited, constitutional union in order to realize its promise of goods ordained by God for men. The Constitution responds to that need. The most evident forms of Constitutional response are visible in the architecture itself. The powers of government are divided into legislative, executive, and judicial branches. Among these, the legislative takes pride of place, being elaborated in Article I and bearing the most careful delineation of powers and principles of representation. This satisfies the concerns of the Declaration, in which the particular enumeration of tyrannical oppressions lists fourteen specific legislative power violations, ten executive power violations, and one judicial power violation. The list of legislative powers in Article I, Section 8 serves as a template by which we may assess the charges against the King as mainly of one or the other tendency. The Constitution established bulwarks where the experience recorded in the Declaration identified dangers. This same pattern is evinced in the Bill of Rights, which opens with the powerful stricture, “Congress shall make no law…”

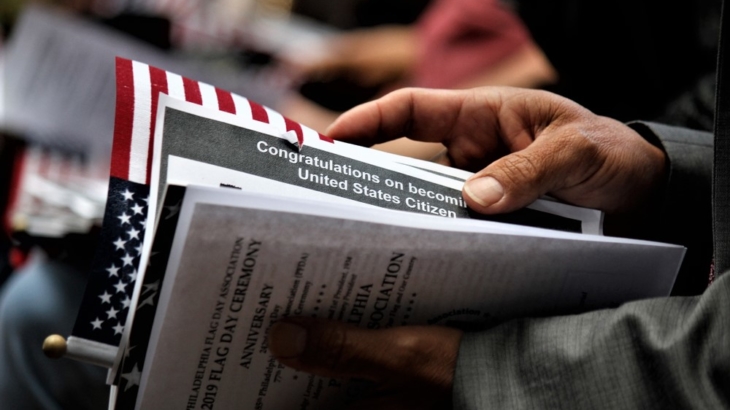

The Second Proof: The Principle of Equality

The most telling evidence of the Constitution’s principles is provided in its architecture. Nevertheless, further, significant dimensions are contained in the language and tenor of the document. The Preamble has oft been noted as keynoting the document in its identification of “We the People” as the authorizing power of the government established under the Constitution. This responds, of course, to the Declaration’s insistence that the public good is the aim of limited, constitutional union. Moreover, it furthers the claim that not artificial, political entities create the United States of America, but the people, exercising a native, God-given right do so. Not less important, however, is the fact that the authorizing people are recognized within the document as fully entitled to serve in the government and to benefit from its ministrations. Those who are eligible to hold office on the Constitution’s own terms are distinguished no further than by reasonable age and citizenship restrictions. No religious test is admitted. No race or gender is excluded. In short, in the vision of the Constitution, “all men are created equal.”

Perhaps the most important affirmation of the Declaration’s constitutionalism is the careful provision for re-balancing, re-forming, and re-directing the government that is contained within the Constitution. The amending provision is evidently the leading, though not the sole, source of this understanding. The constitution is careful to keep the door open to the formation of new political subdivisions within the Union, at the same time as providing guarantees against arbitrary or unwanted re-constitutions of the political subdivisions. In the vision of the Constitution the states are both permanent members of the Union and autonomous members of the Union. The sovereign without their consent may not alter them. Further, political decision making is constrained by a careful regard to establish broad consensus rather than the mere weight of numbers – or, in other words, as nearly as possible all the people must be comprehended in decisions for all and not merely a disproportionate number. Whether the concern is constitutional amendments (which must attract three-fourths of the states), the election of the president (which must attract dispersed majorities throughout the country rather than a merely numerical majority), or the election of representatives (which must work toward broad acceptance rather than merely ideological conformity), the Constitution is a Declaration-minded charter, eager to avoid ever again exposing one part of the empire to the willful neglect or oppression of another part.

The detailed ways in which the Constitution, rhapsode-like, echoes the Declaration are legion and, mercifully, will scarcely reward rehearsal in these premises. (However, an appendix is added to illustrate the relationship.) A notable example is the subordination of the military power to the civil power, and there are many others. Yet, I would insist that nothing so fully explains the Constitution as the Declaration.

What About Slavery?

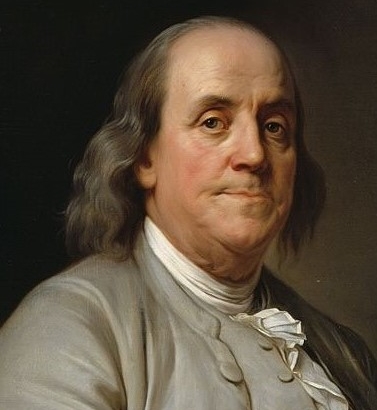

Now it will be reasonable for anyone to insist that the compromises of the Constitution be brought within the compass of these reflections – most notably, the compromises with slavery. Is not slavery the very denial of the Declaration that the Constitution is otherwise said to have echoed? No, we cannot duck this important challenge, for it is certainly correct to say that, if the Constitution were a slave-holding Constitution, then it could not have been a Declaration Constitution. Benjamin Banneker argued as much when he appealed, in 1792, to the author of the Declaration to take up the work of vindicating that document by using his office (as Secretary of State) and reputation (as author of liberty’s charter) to end the abuse that slavery was. Banneker believed that only by eliminating slavery could the Constitution be a true Declaration charter.

I would readily embrace Banneker’s impassioned plea on behalf of the slaves, if I were not already persuaded that the reciprocal influences of the Declaration and the Constitution alone provided in this world any hope for the eventual renunciation of slavery as a lawful practice among men. Although Christianity long before the founding of the United States inseminated moral consciousness with repugnance for slavery, it is doubtless correct to observe that it was only when Christianity combined with the political architecture of liberty that any real opportunity arose to sustain that moral consciousness through the abolition of slavery.

The Constitution, then, compromised with slavery. But in what did the compromise consist? Could it be fairly said that the Constitution purchased its ratification at the cost of approving slavery? Or, was it rather that slave-holding purchased an extended lease at the cost of approving a Declaration charter? I believe the answer to this question is that the latter is nearer the truth than the former. We have not only the testimony of James Madison in the first Congress, who interpreted the slavery clauses in the Constitution as revealing an opposition to slavery albeit in consciousness of the inability to eliminate it at once. We also have the very language of the Constitution itself. The studious avoidance of the word, “slave” – thus to avoid staining the Declaration charter – testifies volubly. Moreover, the tendency of each of the slave-provisions is to provide direct testimony against slavery. At least some proportion of the slaves should be regarded as human beings, for purposes of representation and direct taxation (based on population numbers). That language, the three-fifths clause, was borrowed from a 1783 measure that dealt only with taxation (and therefore led slave-holders to resist the formula rather than support it) and also made plain that all free persons included black persons not slaves. This meant that it was not a comment on the human value of black persons; it was rather a practical measure of the degree of influence the respective sides of the controversy exercised in making the decision. The slave-trading language (“the migration or importation of such persons”) again affirmed the personhood of the slaves. And it did more; it identified the trade as a thing eventually to be ended rather than an option for the future. And the last compromise, the fugitive slave clause, conceded that general laws regarding property should be enforced without exception (thus preserving comity among the states) while yet speaking of “persons held to service,” which included a class larger than slaves.

The slave compromises passed the Constitution, to be sure. But the slave power took the greater risk in doing so. For the other provisions of the Constitution constantly fostering and even encouraging a spreading democratic sentiment could fairly have been expected to deepen the modulated criticism of slavery contained with the compromise language itself. The fact that changing economic and demographic facts in subsequent decades rendered this a more problematic expectation cannot be employed to discount the initial prospects. Nor can it be fairly denied that Lincoln’s valiant and successful effort to recapture the original perspective owed everything to the prior existence of the Declaration charter. When Lincoln and Douglas debated whether the Constitution could apply to black people, and Lincoln reverted to the “standard maxim of a free society” (“that all men are created equal”) to explain the nature of the constitutional principles, we beheld in purest form the sustained, reciprocal interplay of the Declaration and the Constitution. Such a view should persuade us that they are friends never to be separated, best friends in the cause of liberty.

Author’s Note: Keynote address delivered before the New Hampshire Center for Constitutional Studies at its 2004 Constitution Day Celebration, Concord, New Hampshire, September 21, 2004. I acknowledge with gratitude the editorial assistance of my wife, Carol M. Allen. Published in Original Intent vol. 5, no. 1 (December 2004): 1-3, 5.

William B. Allen is Emeritus Dean and Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University.

William B. Allen is Emeritus Dean and Professor of Political Science at Michigan State University.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Appendix

Declaration Constitution

| He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good. | Article. I., Section. 1. All legislative Powers herein granted shall be vested in a Congress of the United States, which shall consist of a Senate and House of Representatives. |

| He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing im- portance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them. | Every Bill which shall have passed the House of Representatives and the Senate, shall, before it become a Law, be presented to the President of the United States: If he approve he shall sign it, but if not he shall return it, with his Objections to that House in which it shall have originated, who shall enter the Objections at large on their Journal, and proceed to reconsider it. If after such Reconsideration two thirds of that House shall agree to pass the Bill, it shall be sent, together with the Objections, to the other House, by which it shall likewise be reconsidered, and if approved by two thirds of that House, it shall become a Law. … If any Bill shall not be returned by the President within ten Days (Sundays excepted) after it shall have been presented to him, the Same shall be a Law, in like Manner as if he had signed it,unless the Congress by their Adjournment prevent its Return, in which Case it shall not be a Law. |

| He has refused to pass other Laws for the accommodation of large districts of people, unless those people would relinquish the right of Representation in the Legislature, a right inestimable to them and formidable to tyrants only. | Section. 2. The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature. |

| He has called together legislative bodies at places unusual, uncomfortable, and distant from the depository of their public Records, for the sole purpose of fatiguing them into compliance with his measures. | The Congress shall assemble at least once in every Year, and such Meeting shall be on the first Monday in December, unless they shall by Law appoint a different Day. |

| He has dissolved Representative Houses repeatedly, for opposing with manly firmness his invasions on the rights of the people. | Neither House, during the Session of Congress, shall, without the Consent of the other, adjourn for more than three days, nor to any other Place than that in which the two Houses shall be sitting. [The President] may, on extraordinary Occasions, convene both Houses, or either of them, and in Case of Disagreement between them, with Respect to the Time of Adjournment, he may adjourn them to such Time as he shall think proper; |

| He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have re- turned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the meantime exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within. | The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators. |

| He has endeavoured to prevent the population of these States; for that purpose obstructing the Laws for Naturalization of Foreigners; refusing to pass others to encourage their migrations hither, and raising the conditions of new Appropriations of Lands. | |

| He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers. | Article III., Section. 1. The judicial Power of the United States shall be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain and establish. |

| He has made Judges dependent on his Will alone, for the tenure of their offices, and the amount and payment of their salaries. | The Judges, both of the supreme and inferior Courts, shall hold their Offices during good Behaviour, and shall, at stated Times, receive for their Services a Compensation, which shall not be diminished during their Continuance in Office. |

| He has erected a multitude of New Offices, and sent hither swarms of Officers to harass our people, and eat out their substance. | [The President] shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States, whose Appointments are not herein otherwise provided for, and which shall be established by Law: but the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the Courts of Law, or in the Heads of Departments. |

| He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislatures. | The Congress shall have Power… To declare War… To provide and maintain a Navy; To make Rules for the Government and Regulation of the land and naval Forces; To provide for calling forth the Militia to execute the Laws of the Union, suppress Insurrections and repel Invasions; To provide for organizing, arming, and disciplining, the Militia, and for governing such Part of them as may be employed in the Service of the United States, reserving to the states respectively, the Appointment of the Officers, and the Authority of training the Militia according to the discipline prescribed by Congress; |

| He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power. | Section. 2. The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the actual Service… |

| He has combined with others to subject us to a jurisdiction foreign to our constitution, and unacknowledged by our laws; giving his Assent to their Acts of pretended Legislation: | Article. VI. … This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land |

| For Quartering large bodies of armed troops among us: | |

| For protecting them, by a mock Trial, from punishment for any Murders which they should commit on the Inhabitants of these States: | |

| For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world: | |

| For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent: | |

| For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury: | |

| For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences | |

| For abolishing the free System of English Laws in a neighbouring Province, establishing therein an Arbitrary government, and enlarging its Boundaries so as to render it at once an example and fit instrument for introducing the same absolute rule into these Colonies: | … no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States. [counters the Quebec Act] |

| For taking away our Charters, abolishing our most valuable Laws, and altering fundamentally the Forms of our Governments: | Section. 4. The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government, and shall protect each of them against Invasion; and on Application of the Legislature, or of the Executive (when the Legislature cannot be convened), against domestic Violence. |

| For suspending our own Legislatures, and declaring themselves invested with power to legislate for us in all cases whatsoever. | |

| He has abdicated Government here, by declaring us out of his Protection and waging War against us. | We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. |

| He has plundered our seas, ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people. | |

| He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances |

| of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation. | |

| He has constrained our fellow Citizens taken Captive on the high Seas to bear Arms against their Country, to become the executioners of their friends and Brethren, or to fall themselves by their Hands. | |

| He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavoured to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes and conditions. |

Click Here To Sign up for the Daily Essay From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Click Here To View the Schedule of Topics From Our 2021 90-Day Study: Our Lives, Our Fortunes & Our Sacred Honor

Michael P. Farris is president and CEO of Alliance Defending Freedom. As the second CEO of ADF, he brings to the role a diverse background as an effective litigator, educator, public advocate, and communicator, and is widely recognized for his successful work on both the national and international stage.

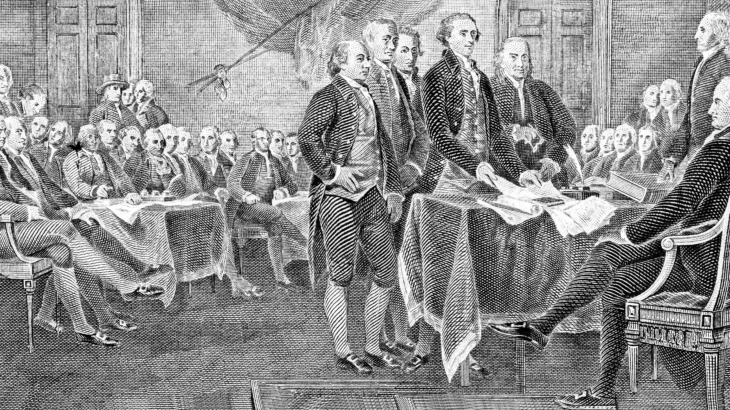

Michael P. Farris is president and CEO of Alliance Defending Freedom. As the second CEO of ADF, he brings to the role a diverse background as an effective litigator, educator, public advocate, and communicator, and is widely recognized for his successful work on both the national and international stage. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signing_of_the_United_States_Declaration_of_Independence#/media/File:Signing_of_Declaration_of_Independence_by_Armand-Dumaresq,_c1873.png Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

Tony Williams is a Senior Fellow at the Bill of Rights Institute and is the author of six books including Washington and Hamilton: The Alliance that Forged America with Stephen Knott. Williams is currently writing a book on the Declaration of Independence.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also the chair of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky.

James C. Clinger is a professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology at Murray State University. Dr. Clinger teaches courses in state and local government, Kentucky politics, intergovernmental relations, regulatory policy, and public administration. Dr. Clinger is also the chair of the Murray-Calloway County Transit Authority Board and a past president of the Kentucky Political Science Association. He currently resides in Hazel, Kentucky.

J. Edward Lee, Ph.D., is Professor of History at Winthrop University. Lee is a former mayor of the City of York, South Carolina.

J. Edward Lee, Ph.D., is Professor of History at Winthrop University. Lee is a former mayor of the City of York, South Carolina.

Barb Zakszewski is a wife, mother and grandmother, lifelong conservative, regular civic volunteer and writer.

Barb Zakszewski is a wife, mother and grandmother, lifelong conservative, regular civic volunteer and writer.

Jeff Broadwater is professor emeritus of history at Barton College in Wilson, North Carolina, where he taught courses on the American Revolution and on the history of the American South. His publications include Jefferson, Madison, and the Making of the Constitution (2019); James Madison, A Son of Virginia and a Founder of of the Nation (2012); and George Mason, Forgotten Founder (2006). He also co-edited, with Troy Kickler, North Carolina’s Revolutionary Founders (2019).

Jeff Broadwater is professor emeritus of history at Barton College in Wilson, North Carolina, where he taught courses on the American Revolution and on the history of the American South. His publications include Jefferson, Madison, and the Making of the Constitution (2019); James Madison, A Son of Virginia and a Founder of of the Nation (2012); and George Mason, Forgotten Founder (2006). He also co-edited, with Troy Kickler, North Carolina’s Revolutionary Founders (2019).

Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and two grandchildren.

Jay McConville is a military veteran, management professional, and active civic volunteer currently pursuing a Ph.D. in Public Policy and Administration at the L. Douglas Wilder School of Government and Public Affairs, Virginia Commonwealth University. Prior to beginning his doctoral studies, he held multiple key technology and management positions within the Aerospace and Defense industry, including twice as President and CEO. He served in the U.S. Army as an Intelligence Officer, and has also been active in civic and industry volunteer associations, including running for elected office, serving as a political party chairman, and serving multiple terms as President of both his industry association’s Washington DC Chapter and his local youth sports association. Today he serves on the Operating Board of Directors of Constituting America. He has a Bachelor of Arts in Government from George Mason University, and a Master of Science in Strategic Intelligence from the Defense Intelligence College. Jay lives in Richmond with his wife Susan Ulsamer McConville. They have three children and two grandchildren.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Andrew Langer is President of the Institute for Liberty.

Val Crofts serves as Chief Education and Programs Officer at the American Village in Montevallo, Alabama. Val previously taught high school U.S. History, U.S. Military History and AP U.S. Government for 19 years in Wisconsin, and was recipient of the DAR Outstanding U.S. History Teacher of the Year for the state of Wisconsin in 2019-20. Val also taught for the Wisconsin Virtual School as a social studies teacher for 9 years. He is also a proud member of the United States Semiquincentennial Commission (America 250), which is currently planning events to celebrate the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence.

Val Crofts serves as Chief Education and Programs Officer at the American Village in Montevallo, Alabama. Val previously taught high school U.S. History, U.S. Military History and AP U.S. Government for 19 years in Wisconsin, and was recipient of the DAR Outstanding U.S. History Teacher of the Year for the state of Wisconsin in 2019-20. Val also taught for the Wisconsin Virtual School as a social studies teacher for 9 years. He is also a proud member of the United States Semiquincentennial Commission (America 250), which is currently planning events to celebrate the 250th birthday of the Declaration of Independence.

William M.S. Rasmussen serves as Senior Museum Collections Curator & Lora M. Robins Curator of Art at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. He is co-author of The Story of Virginia, Highlights from the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, with Jamie O. Bosket, among many other books and articles on Virginia history.

William M.S. Rasmussen serves as Senior Museum Collections Curator & Lora M. Robins Curator of Art at the Virginia Museum of History & Culture. He is co-author of The Story of Virginia, Highlights from the Virginia Museum of History & Culture, with Jamie O. Bosket, among many other books and articles on Virginia history.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Suzanne Munson is author of the George Wythe biography, Jefferson’s Godfather: The Man Behind the Man. She lectures frequently on the Wythe-Jefferson legacy at university affiliates, historical societies, and other venues. She is currently writing a new book, America’s First Leadership Crisis: 1776.

Suzanne Munson is author of the George Wythe biography, Jefferson’s Godfather: The Man Behind the Man. She lectures frequently on the Wythe-Jefferson legacy at university affiliates, historical societies, and other venues. She is currently writing a new book, America’s First Leadership Crisis: 1776.

Colleen A. Sheehan is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies with the

Colleen A. Sheehan is Professor and Director of Graduate Studies with the

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Ron Meier is a West Point graduate and Vietnam War veteran. He is a student of American history, with a focus on our nation’s founding principles and culture, the Revolutionary War, and the challenges facing America’s Constitutional Republic in the 20th and 21st centuries. Ron won Constituting America’s Senior Essay contest in 2014 and is author of Common Sense Rekindled: A Rejuvenation of the American Experiment, featured on Constituting America’s Recommended Reading List.

Gordon Lloyd is the Robert and Katheryn Dockson Professor of Public Policy at

Gordon Lloyd is the Robert and Katheryn Dockson Professor of Public Policy at

Robert M. S. McDonald is Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at

Robert M. S. McDonald is Professor of History at the United States Military Academy at

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Gary Porter is Executive Director of the

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of

Tom Hand is creator and publisher of

William J. Federer is a nationally known speaker and best-selling author of many books including “America’s God and Country Encyclopedia of Quotations” which has sold over a half-million copies. He is president of

William J. Federer is a nationally known speaker and best-selling author of many books including “America’s God and Country Encyclopedia of Quotations” which has sold over a half-million copies. He is president of

Heather Brubaker Bailey, who now lives in New Jersey, is a descendent of Abraham Clark. Heather graduated from Elizabethtown College and now works as a real estate agent in Morristown, New Jersey.

Heather Brubaker Bailey, who now lives in New Jersey, is a descendent of Abraham Clark. Heather graduated from Elizabethtown College and now works as a real estate agent in Morristown, New Jersey.

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else.

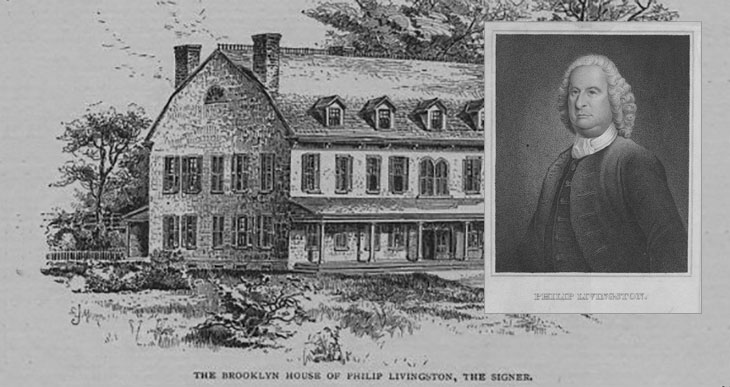

Dan Cotter is Attorney and Counselor at Howard & Howard Attorneys PLLC. He is the author of The Chief Justices, (published April 2019, Twelve Tables Press). He is also a past president of The Chicago Bar Association. The article contains his opinions and is not to be attributed to anyone else. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lewis_Morris_painting.jpg - Public Domain Image, cropped

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Lewis_Morris_painting.jpg - Public Domain Image, cropped

Richard Sala is a retired Marine Corps Judge Advocate and currently serves as the Academic Success Program Director and Assistant Professor of Law at

Richard Sala is a retired Marine Corps Judge Advocate and currently serves as the Academic Success Program Director and Assistant Professor of Law at

Robert Brescia, Ed.D., serves as a Board Director, Past Chairman, at Basin PBS Television. He has served in top leadership roles in education, corporate business, nonprofit, and defense with twenty-seven years of public service as an Airborne Ranger Cavalry Soldier, NCO, and Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Army. Mr. Brescia was appointed by Texas Governor Greg Abbott to the State Board for Educator Certification.

Robert Brescia, Ed.D., serves as a Board Director, Past Chairman, at Basin PBS Television. He has served in top leadership roles in education, corporate business, nonprofit, and defense with twenty-seven years of public service as an Airborne Ranger Cavalry Soldier, NCO, and Commissioned Officer in the U.S. Army. Mr. Brescia was appointed by Texas Governor Greg Abbott to the State Board for Educator Certification.

Eric Wise is an attorney practicing in New York.

Eric Wise is an attorney practicing in New York.

Jeanne McKinney is an award-winning writer whose focus and passion is our United States active-duty military members and military news. Her Patriot Profiles offer an inside look at the amazing active-duty men and women in all Armed Services, including U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, Air Force, Coast Guard, and National Guard. Reporting includes first-hand accounts of combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the fight against violent terror groups, global defense, tactical training and readiness, humanitarian and disaster relief assistance, next-generation defense technology, family survival at home, U.S. port and border protection and illegal immigration, women in combat, honoring the Fallen, Wounded Warriors, Military Working Dogs, Crisis Response, and much more. Starting in 2012, McKinney has won multiple San Diego Press Club “Excellence in Journalism Awards,” including eight “First Place” honors, as well as multiple second and third place recognition for her Patriot Profiles published printed articles. Including awards for Patriot Profiles military films. During the year 2020, McKinney has written and published dozens of investigative articles in her ongoing fight to preserve America the Republic, the Constitution, and its laws. One such story was selected for use in a legal brief in the national fight for 2020 election integrity.

Jeanne McKinney is an award-winning writer whose focus and passion is our United States active-duty military members and military news. Her Patriot Profiles offer an inside look at the amazing active-duty men and women in all Armed Services, including U.S. Marine Corps, Navy, Army, Air Force, Coast Guard, and National Guard. Reporting includes first-hand accounts of combat missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, the fight against violent terror groups, global defense, tactical training and readiness, humanitarian and disaster relief assistance, next-generation defense technology, family survival at home, U.S. port and border protection and illegal immigration, women in combat, honoring the Fallen, Wounded Warriors, Military Working Dogs, Crisis Response, and much more. Starting in 2012, McKinney has won multiple San Diego Press Club “Excellence in Journalism Awards,” including eight “First Place” honors, as well as multiple second and third place recognition for her Patriot Profiles published printed articles. Including awards for Patriot Profiles military films. During the year 2020, McKinney has written and published dozens of investigative articles in her ongoing fight to preserve America the Republic, the Constitution, and its laws. One such story was selected for use in a legal brief in the national fight for 2020 election integrity.

Tara Ross is nationally recognized for her expertise on the Electoral College. She is the author of Why We Need the Electoral College (2019), The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders’ Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule (2017), We Elect A President: The Story of our Electoral College (2016), and Enlightened Democracy: The Case for the Electoral College (2d ed. 2012). She is also the author of She Fought Too: Stories of Revolutionary War Heroines (2019), and a co-author of Under God: George Washington and the Question of Church and State (2008) (with Joseph C. Smith, Jr.). Her Prager University video, Do You Understand the Electoral College?, is Prager’s most-viewed video ever, with more than 60 million views.

Tara Ross is nationally recognized for her expertise on the Electoral College. She is the author of Why We Need the Electoral College (2019), The Indispensable Electoral College: How the Founders’ Plan Saves Our Country from Mob Rule (2017), We Elect A President: The Story of our Electoral College (2016), and Enlightened Democracy: The Case for the Electoral College (2d ed. 2012). She is also the author of She Fought Too: Stories of Revolutionary War Heroines (2019), and a co-author of Under God: George Washington and the Question of Church and State (2008) (with Joseph C. Smith, Jr.). Her Prager University video, Do You Understand the Electoral College?, is Prager’s most-viewed video ever, with more than 60 million views.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Winfield H. Rose, Ph.D., is Distinguished Professor of Political Science Emeritus at Murray State University.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Scot Faulkner is Vice President of the George Washington Institute of Living Ethics at Shepherd University. He was the Chief Administrative Officer of the U.S. House of Representatives. Earlier, he served on the White House staff. Faulkner provides political commentary for ABC News Australia, Newsmax, and CitizenOversight. He earned a Master’s in Public Administration from American University, and a BA in Government & History from Lawrence University, with studies in comparative government at the London School of Economics and Georgetown University.

Steven H. Aden serves as Chief Legal Officer & General Counsel at Americans United for Life. Aden joined Americans United for Life in August 2017, overseeing all legal operations of America’s most effective pro-life organization. Aden is a highly experienced litigator, having appeared in court against Planned Parenthood and the abortion industry dozens of times and appointed by the attorneys general of six states to defend pro-life laws. A prolific author and analyst on sanctity of life issues and constitutional jurisprudence, Aden is admitted to the bars of the District of Columbia, Virginia, and Hawaii (inactive), and is a member of the bars of the U.S. Supreme Court and numerous federal circuit and district courts. He has practiced law since 1990 and earned his J.D. (cum laude) from Georgetown University Law Center and his B.A. from the University of Hawaii.

Steven H. Aden serves as Chief Legal Officer & General Counsel at Americans United for Life. Aden joined Americans United for Life in August 2017, overseeing all legal operations of America’s most effective pro-life organization. Aden is a highly experienced litigator, having appeared in court against Planned Parenthood and the abortion industry dozens of times and appointed by the attorneys general of six states to defend pro-life laws. A prolific author and analyst on sanctity of life issues and constitutional jurisprudence, Aden is admitted to the bars of the District of Columbia, Virginia, and Hawaii (inactive), and is a member of the bars of the U.S. Supreme Court and numerous federal circuit and district courts. He has practiced law since 1990 and earned his J.D. (cum laude) from Georgetown University Law Center and his B.A. from the University of Hawaii.

NationalAtlas.gov

NationalAtlas.gov

John G. McCurdy is Professor of History at Eastern Michigan University. He is the author of Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution. He regularly teaches courses on early American history.

John G. McCurdy is Professor of History at Eastern Michigan University. He is the author of Quarters: The Accommodation of the British Army and the Coming of the American Revolution. He regularly teaches courses on early American history.

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA serves on the Board of Trustees for the Lone Star College System and teaches political science at the University of Houston and is an affiliated scholar with the Baylor College of Medicine’s Center for Health Policy and Medical Ethics. Kyle has authored over 70 op-eds, dozens of academic articles and five books, the most recent of which is The Limits of Politics: Making the Case for Literature in Political Analysis. He can be reached at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com or on Twitter: @kanthonyscott.

Kyle Scott, PhD, MBA serves on the Board of Trustees for the Lone Star College System and teaches political science at the University of Houston and is an affiliated scholar with the Baylor College of Medicine’s Center for Health Policy and Medical Ethics. Kyle has authored over 70 op-eds, dozens of academic articles and five books, the most recent of which is The Limits of Politics: Making the Case for Literature in Political Analysis. He can be reached at kyle.a.scott@hotmail.com or on Twitter: @kanthonyscott.

David L. Robbins serves as Public Education Commissioner in New Mexico.

David L. Robbins serves as Public Education Commissioner in New Mexico.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

George

George