Essay Read By Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Religious freedom, assembling, speaking freely and defending the nation’s liberty. “While the People are virtuous they cannot be subdued; but when once they lose their Virtue they will be ready to surrender their Liberties to the first external or internal Invader. How necessary then is it for those who are determind to transmit the Blessings of Liberty as a fair Inheritance to Posterity, to associate on publick Principles in Support of publick Virtue. I do verily believe, and I may say it inter Nos, that the Principles & Manners of New England produced that Spirit which finally has establishd the Independence of America; and Nothing but opposite Principles and Manners can overthrow it.” – Samuel Adams, in a letter to James Warren, Philadelphia, February 12, 1779.

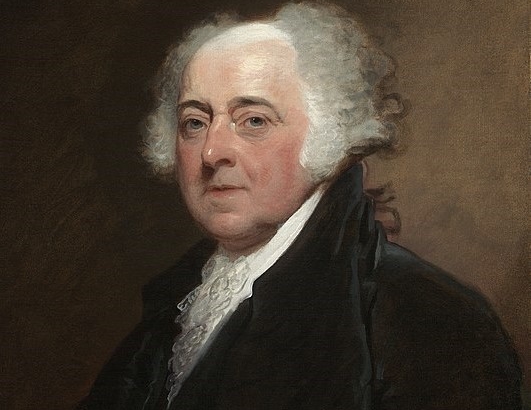

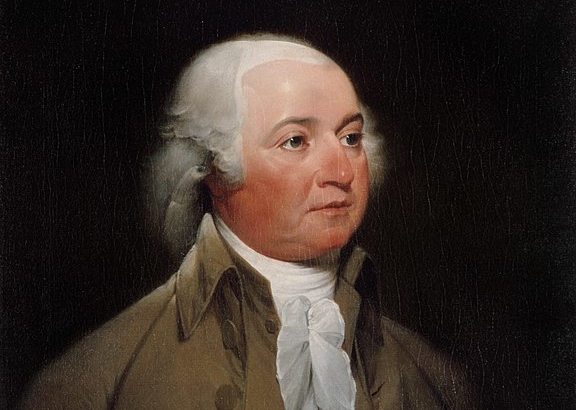

In A Defence of the Constitutions of Government of the United States, John Adams mused about a lengthy quote from Aristotle’s Politics. There, Aristotle extols the benefits of a polis controlled by a broad middle class and warns of the danger to societies if the number of the middle class dwindles. His assessment of the best practical political system is consistent with what is called the “Golden Mean,” a concept taken from Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics. For the most part, excellence of the soul—virtue—lies in taking a path between two extremes that are vices. Another key element of classical Greek philosophy was that excellence of the person and of the state were intimately connected, that the polis was the soul writ large, so the analogy of the benefits of moderation for the individual to the benefits of middle-class government for the state was obvious.

It is worth quoting Aristotle at length on this point, as Adams did:

“In every city the people are divided into three sorts, the very rich, the very poor, and the middle sort. If it is admitted that the medium is the best, it follows that, even in point of fortune, a mediocrity is preferable. The middle state is most compliant to reason. Those who are very beautiful, or strong, or noble, or rich, or, on the contrary, those who are very poor, weak, or mean, with difficulty obey reason.… A city composed only of the rich and the poor, consists but of masters and slaves, not freemen; where one party despise, and the other hate; where there is no possibility of friendship, or political community, which supposes affection. It is the genius of a free city to be composed, as much as possible, of equals; and equality will be best preserved when the greatest part of the inhabitants are in the middle state. These will be best assured of safety as well as equality; they will not covet nor steal, as the poor do, what belongs to the rich; nor will what they have be coveted or stolen; without plotting against any one, or having any one plot against them, they will live free from danger. For which reason, Phocylides wisely wishes for the middle state, as being most productive of happiness. It is plain then that the most perfect community must be among those who are in the middle rank; and those states are best instituted, wherein these are a larger and more respectable part, if possible, than both the other; or, if that cannot be, at least than either of them separate; so that, being thrown into the balance, it may prevent either scale from preponderating. It is, therefore, the greatest happiness which the citizen can enjoy, to possess a moderate and convenient fortune. When some possess too much, and others nothing at all, the government must either be in the hands of the meanest rabble, or else a pure oligarchy. The middle state is best, as being least liable to those seditions and insurrections which disturb the community; and for the same reason extensive governments are least liable to these inconveniences; for there those in the middle state are very numerous; whereas, in small ones, it is easy to pass to the two extremes, so as hardly to have any medium remaining, but the one half rich, and the other poor. We ought to consider, as a proof of this, that the best lawgivers were those in the middle rank of life, among whom was Solon, as is evident from his poems, and Lycurgus, for he was not a king; and Charondas, and, indeed, most others. Hence, so many free states have changed either to democracies or oligarchies; for whenever the number of those in the middle state has been too small, those who were the more numerous, whether the rich or the poor, always overpowered them, and assumed to themselves the administration. When, in consequence of their disputes and quarrels with each other, either the rich get the better of the poor, or the poor of the rich, neither of them will establish a free state, but, as a record of their victory, will form one which inclines to their own principles, either a democracy or an oligarchy….”

This critique of pure oligarchic or democratic systems has been summed up as the unwelcome prospect of the rich stealing from the poor in the former, and the poor stealing from the rich in the latter.

Adams quoted this passage with approbation, but occasionally expressed opinions which seemed to be at odds with Aristotle’s political theory. Aristotle proposed a mixed government (mikte) as the most stable and conducive to human flourishing. The mixed government would not be democratic or oligarchic but would have elements of both in a mediated balance, such as in Athens, where the popular Assembly was balanced by the Council of 500 and its steering committee. Adams’s own work in drafting the Massachusetts Constitution of 1780 incorporated a similar bicameral structure in a Senate and a House of Representatives, with qualification for election to the former requiring ownership of an estate three times the value of property needed for election to the latter. But he also put in place a further structure of separation and balance of powers among the three branches of government, explicitly affirmed in Article XXX of that constitution, so that “it may be a government of laws and not of men.”

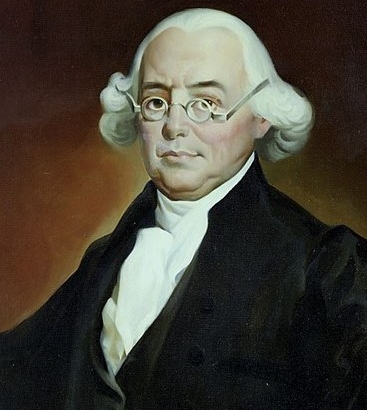

Aristotle’s description of the instability of pure systems such as oligarchy and democracy was not new with him. Plato and other Greeks had done likewise. American writers had similar misgivings. James Madison addressed such instability in his writings in The Federalist, especially in his discussion of factions in essay No. 10. Aristotle’s observation that “extensive governments are least liable to these inconveniences; for there those in the middle state are very numerous; whereas, in small ones, it is easy to pass to the two extremes, so as hardly to have any medium remaining, but the one half rich, and the other poor,” sounds remarkably like Madison’s defense of the national government.

Factions are the result of the inevitable inequality of rights in property which proceeds from the natural inequality of talents. “Those who hold, and those who are without property, have ever formed distinct interests in society.” Moreover, because of the inherent nature of democracies, where a small number of citizens conducts the government in person, those factions are most likely to become entrenched, with the stronger party sacrificing the weaker. “Hence it is, that such democracies have ever been spectacles of turbulence and contention; have ever been found incompatible with personal security, or the rights of property; and have, in general, been as short in their lives, as they have been violent in their deaths.” This remark might as well have been a summary of Athenian politics. Again, Aristotle’s observation, “When, in consequence of their disputes and quarrels with each other, either the rich get the better of the poor, or the poor of the rich, neither of them will establish a free state,” matches Madison’s critique.

The instability and short survival of democracies carried over to other small political entities.

“The smaller the society, the fewer probably will be the distinct parties and interests composing it; the fewer the distinct parties and interests, the more frequently will a majority be found of the same party; and the smaller the number of individuals composing the majority, and the smaller the compass within which they are placed, the more easily will they concert and execute their plan of oppression….[T]he same advantage, which a republic has over a democracy, in controling the effects of faction, is enjoyed by a large over a small republic…is enjoyed by the union over the states composing it.”

Specifically,

“…a religious sect may degenerate into a political faction in a part of the confederacy; but the variety of sects dispersed over the entire face of it, must secure the national councils against any danger from that source: a rage for paper money, for an abolition of debts, for an equal division of property, or for any other improper or wicked project, will be less apt to pervade the whole body of the union, than a particular member of it; in the same proportion as such a malady is more likely to taint a particular county or district than an entire state.”

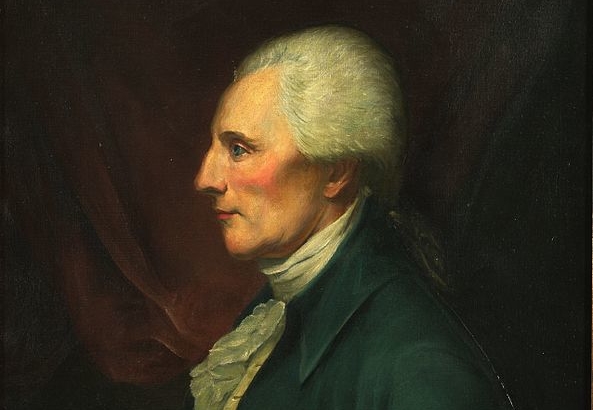

Samuel Adams’s letter to James Warren quoted in the introduction to this essay tied stable government and individual liberty to virtue and bound private and public virtue to each other. This emphasis on the interdependent virtue of the citizen and of the society was the essence of classical republicanism and a fundamental concept in the political philosophy of Greek and Roman writers. Moreover, Adams confided to his fellow New Englander that it was the “Principles & Manners” of that region which produced the spirit of liberty that fueled the drive to American independence. In the views of many New Englanders, especially Samuel’s cousin John Adams, widely-distributed land ownership of medium size lay at the heart of developing those New England principles that allowed for private and public virtue to take root.

In that letter to Warren, Adams also echoed Aristotle’s identification of a free city with a large middle class, whose ownership of a moderate estate made them most receptive to governance based on reason. Government by reason is analogous to the exercise of public or civic virtue and is most conducive to happiness (eudaimonia). When Aristotle declares, “It is plain then that the most perfect community must be among those who are in the middle rank,” he is associating excellence of government with a middle-class society. Excellence was arete in Greek. In Rome, the Latin translation became virtus and denoted a particular type of attribute and action that connected private character and public conduct.

The inevitable link between widespread property ownership of land, a virtuous citizenry, liberty, and survival of republican government was a common theme outside New England, as well. Although property ownership in the South was somewhat more complex due to the existence of the planter class in the Tidewater regions, other regions of the area still had a large class of yeoman farmers with moderate estates. Two of the most prominent advocates of Southern agrarian republicanism were Thomas Jefferson and John Taylor. Jefferson sought to realize his idealized virtuous republic of artisans and yeoman farmers politically through his promotion of land sales in the Old Northwest and the acquisition of Louisiana. Taylor’s writings on land ownership, virtue, liberty, and republican institutions brought systematic cohesion to agrarian republicanism and tied its principles to contentious issues of public policy.

But faith in a virtuous middle class as the source of personal liberty and political stability was not blind. Various writers, including John Adams in 1776, expressed reservations about the capacity of Americans to acquire the virtue necessary for self-government. New Englanders’ faith in their virtue and their fitness for republican government was shaken severely by the tax rebellion of Daniel Shays and his followers in 1786. Perhaps such virtue was not possible without a strong hand of government to correct deviations. More Americans were forced to confront that issue during and after the Whiskey Tax Rebellion in Pennsylvania from 1791 to 1794. After all, in both scenarios, the challenge to the republican governments had come from yeoman farmers, the supposed embodiments of republican virtue.

Southern agrarians had always been more skeptical that there was sufficient virtue among politicians to maintain republican government. Their experience with the turbulence and corruption of state governments after independence only confirmed their doubts. Madison expressed that sentiment in essay No. 51 of The Federalist. While there was some basis to believe that the people might acquire the requisite virtue, in the case of politicians it was best to assume that “the better angels of [their] nature,” to borrow Abraham Lincoln’s famous language from years later, would not direct their actions. It was more likely that pure self-interest and desire for power would be their motivation.

Therefore,

“[a]mbition must be made to counteract ambition. The interest of the man must be connected with the constitutional rights of the place. It may be a reflection on human nature, that such devices should be necessary to control the abuses of government. But what is government itself, but the greatest of all reflections on human nature? If men were angels, no government would be necessary. If angels were to govern men, nether external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself. A dependence on the people is, no doubt, the primary control on the government; but experience has taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.”

Those auxiliary precautions lay in the structure of the government under the Constitution, primarily a separation of powers and blending and overlapping of functions as in John Adams’s Massachusetts constitution.

Madison was not alone in declining to place all bets for success of republican self-government and liberty on human virtue. Samuel Adams may have been correct that those “Blessings of Liberty” cannot be passed on without cultivating virtue in the people, especially the virtues of the Aristotelian golden mean. Self-government requires self-restraint. But virtue, though necessary, may not be sufficient. “The best republics will be virtuous, and have been so,” the other Adams—John—concluded in the last pages of the multivolume Defence in the somewhat stilted syntax of his time,

“But we may hazard a conjecture, that the virtues have been the effect of the well-ordered constitution, rather than the cause: and perhaps it would be impossible to prove, that a republic cannot exist, even among highwaymen, by setting one rogue to watch another; and the knaves themselves may, in time, be made honest men by the struggle.”

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Click here for First Principles of the American Founding 90-Day Study Schedule.

Click here to receive our Daily 90-Day Study Essay emailed directly to your inbox.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayflower_Compact

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Essay Read by Constituting America Founder, Actress Janine Turner

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cambodian_genocide https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Croly

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herbert_Croly

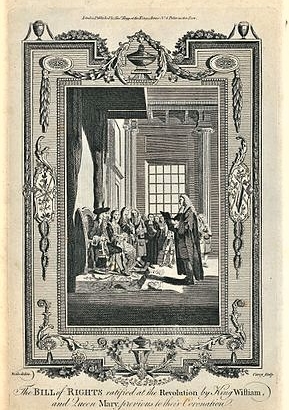

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_of_Rights_1689#/media/File:Samuel_Wale,_The_Bill_of_Rights_Ratified_at_the_Revolution_by_King_William,_and_Queen_Mary,_Previous_to_their_Coronation_(1783).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli#/media/File:Portrait_of_Niccol%C3%B2_Machiavelli_by_Santi_di_Tito.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Veen01.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eighty_Years%27_War#/media/File:Veen01.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crown_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire#/media/File:Holy_Roman_Empire_Crown_(Imperial_Treasury)2.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Imperial_Crown_of_the_Holy_Roman_Empire#/media/File:Holy_Roman_Empire_Crown_(Imperial_Treasury)2.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Venitian_ford_at_Navlion.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_the_Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Venitian_ford_at_Navlion.jpg Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty. Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Archive-ugent-be-79D46426-CC9D-11E3-B56B-4FBAD43445F2_DS-240_(cropped).jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Republic_of_Venice#/media/File:Archive-ugent-be-79D46426-CC9D-11E3-B56B-4FBAD43445F2_DS-240_(cropped).jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Forum_Romanum_through_Arch_of_Septimius_Severus_Forum_Romanum_Rome.jpg

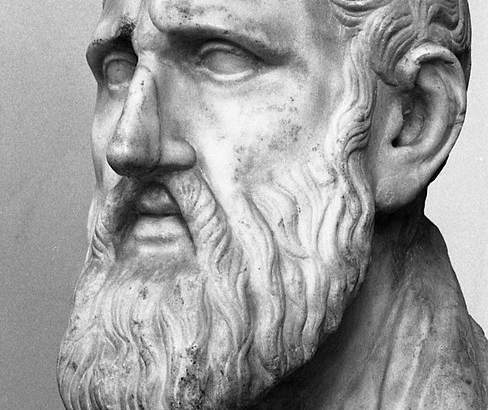

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roman_Republic#/media/File:Forum_Romanum_through_Arch_of_Septimius_Severus_Forum_Romanum_Rome.jpg https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism#/media/File:Paolo_Monti_-_Servizio_fotografico_(Napoli,_1969)_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stoicism#/media/File:Paolo_Monti_-_Servizio_fotografico_(Napoli,_1969)_-_BEIC_6353768.jpg

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Podcast by Maureen Quinn.

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Joerg W. Knipprath is an expert on constitutional law, and member of the Southwestern Law School faculty, Professor Knipprath has been interviewed by print and broadcast media on a number of related topics ranging from recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions to presidential succession. He has written opinion pieces and articles on business and securities law as well as constitutional issues, and has focused his more recent research on the effect of judicial review on the evolution of constitutional law. He has also spoken on business law and contemporary constitutional issues before professional and community forums, and serves as a Constituting America Fellow. Read more from Professor Knipprath at:

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

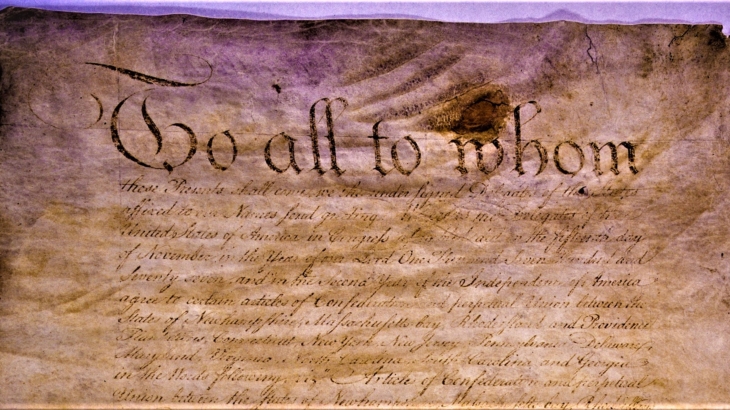

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Articles_of_Confederation#/media/File:Articles_page1.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patrick_Henry#/media/File:Patrick_Henry_Rothermel.jpg